Analysis

January 23, 2026

Doderer on the economy: Will economic factors yield more steel demand?

Written by Daniel Doderer

Over the last month, as additional industrial data has filtered through, very little has substantively changed since my last econ last column:

- The ISM Manufacturing PMI slipped further in December, down 0.3 to its lowest reading of the year at 47.9 and now in contraction for 10 straight months.

- Total construction spending (SA) rebounded in October, up 0.5% but down 1% compared to last year’s levels. The increase was driven by a 1.3% monthly rise in residential construction spending, while the spending on manufacturing facilities continued the 9-month skid, down 0.9% this month as well.

- Auto sales (SAAR) rose in November to 15.9 million but came in at the second lowest reading of 2025, while production in September remains painfully low at 102,000 units produced (SA).

What will be more important than a discussion of those immediate fluctuations, however, would be a deeper examination of where we likely stand on the assumptions highlighted in last month’s column.

Specifically, for today – the Federal Reserve’s interest rate policy. At the time of writing, the idea that Fed Chair Jerome Powell was finished with cuts for his tenure was not inconceivable but certainly against consensus. Most in the broader forecaster/economist community came into the year expecting from one to three more, with those cuts being frontloaded to the first half of the year.

However, following political pressure on Powell, the futures market is now pricing in one cut for all of 2026, and not until after Powell is no longer chair.

Let’s step away from the shifting winds of political machinations, and revisit why expectations were once so wide is an important exercise. Because those same underlying forces will ultimately determine where interest rates settle.

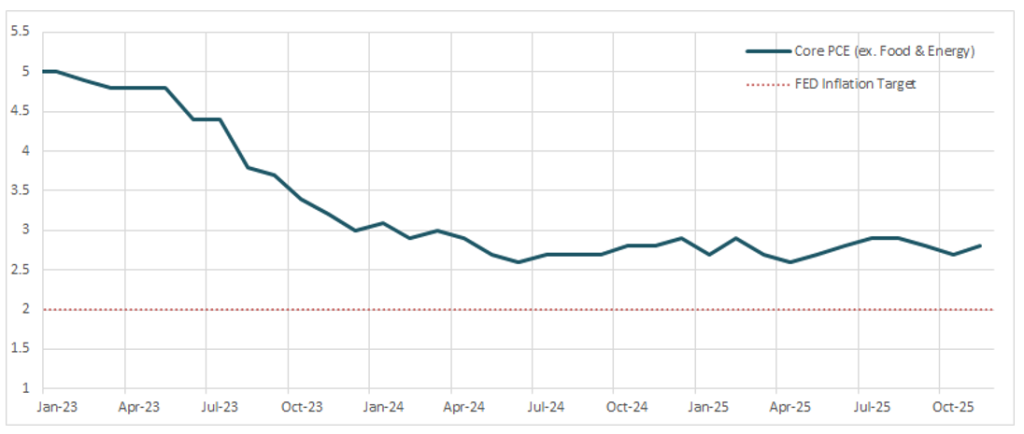

Over the coming months, an awareness of how norms in labor market data have changed will be vital, because stickiness in inflation (see chart below) is unlikely to shift in a way that would cause the Fed to be confident that prices are anchored to their 2% target, especially given the fact that today’s November Core PCE release showed an increase to 2.8%, up from 2.7% in October.

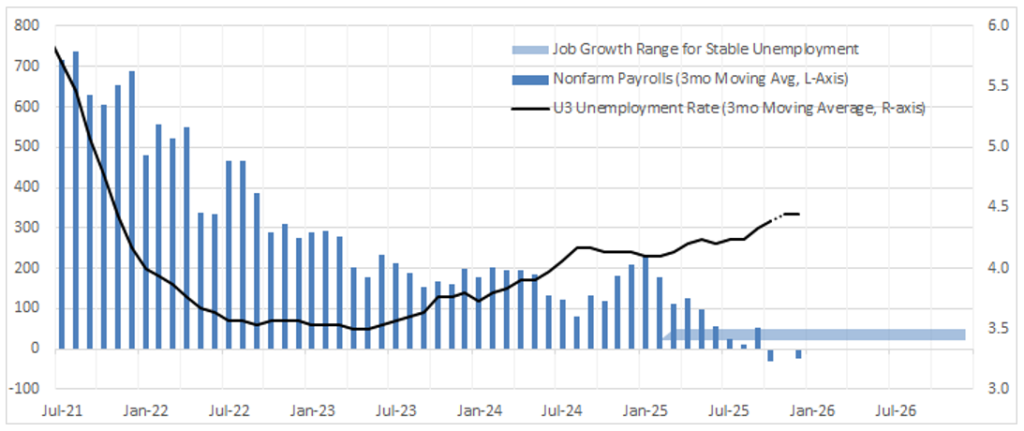

This leads us to the labor market. Today, unemployment stands at 4.4%, down 0.1 percentage point from November’s 50-month high.

In the context of slowing population growth, and with recent estimates (Brookings) suggesting that 2025 marked the first year of negative net immigration since the mid-1970s, the economy now requires far fewer job gains to keep unemployment from rising.

Monthly payroll growth in the 20,000 to 50,000 range may be enough to stabilize the labor market, a notably lower threshold than in prior cycles.

The chart below highlights how quickly labor market dynamics have shifted. The blue bars represent the three-month moving average of nonfarm payrolls, the black line represents the three-month moving average of the unemployment rate, and the shaded region represents that 20-50k range needed to be stable.

That adjustment is being reinforced by other constructive labor dynamics. Prime-age labor force participation remains near cycle highs, helping offset demographic drag, while wage growth has moderated without collapsing and has recently surprised to the upside. Together, these trends point to a labor market that has cooled but is not continuing to weaken – supporting the case for patience rather than urgency from the Fed.

The key takeaway is that elevated financing costs are likely to remain a headwind that must be worked through rather than waited out. Even if the Fed cuts rates further, financial conditions are no longer moving in lockstep with policy: since the first cut, the Fed funds target range is 175 basis points lower, while the 10-year Treasury yield is roughly 57 basis points higher, sitting near 4.26% and largely above 4% since October.

For commodity markets like steel, these levels of financing costs are less likely to derail large, long-term investment decisions and more likely to temper near-term purchasing behavior. It raises the bar for inventory rebuilds, production pacing, and spot buying. The result is greater pressure on near-term price discovery and increased sensitivity to incremental demand shifts. Demand will still emerge, but under closer scrutiny, with price volatility increasingly reflecting real end-use pull rather than broader macro or financial conditions alone.