Market Data

July 19, 2015

A Brief History of Steel Mill Labor Negotiations

Written by Sandy Williams

Contract negotiations are currently underway between the United Steel Workers and steel companies US Steel and ArcelorMittal. The companies each met with USW bargaining committee members in Pittsburgh to begin working out details of new three-year contracts to replace the current ones expiring Sept. 1.

USW Committee members are expecting the first proposal from ArcelorMittal sometime in the coming week. Even so, AM has been positioning their position on the Company blog which can be found on the ArcelorMittal USA website.

Contract negotiations are a time consuming dance between management and union. Each hopes to take the lead in the dance and spin its partner to a favorable contract conclusion. The steps along the way can be delicate, forceful or stuttering but the dance always concludes with a compromise.

Steel Market Update thought it might be interesting to take a look at what happened three years ago and then explore some of the major events in collective bargaining that have occurred since unions first made their entry to the steel industry.

Recap of 2012 Negotiations

During the last negotiation period in 2012, ArcelorMittal asked the union to cut wages by 36 percent and eliminate retiree benefits for new hires. The company also asked for the right to cut wages and hours worked in times of reduced production.

Contract issues for US Steel focused on rising health care and pension costs for current and retired employees.

US Steel and the USW reached a tentative agreement before the Sept 1 expiration date. The contract was ratified on Sept. 26 and protected health care benefits for retirees as well as providing a 2 percent wage increase during the first year of the contract followed by a 2.5 percent increase at the beginning of 2014, and $2500 in bonuses over the life of the contract.

US Steel and the USW reached a tentative agreement before the Sept 1 expiration date. The contract was ratified on Sept. 26 and protected health care benefits for retirees as well as providing a 2 percent wage increase during the first year of the contract followed by a 2.5 percent increase at the beginning of 2014, and $2500 in bonuses over the life of the contract.

ArcelorMittal took a hardline on its demands and began preparations for a work stoppage in anticipation of union resistance. The USW did not take a strike vote but instead embarked on a campaign of demonstrations and protests. On October 18, the USW voted to ratify the contract by a 94.3 percent margin. About 30 percent of the 14,601 eligible voting members declined to vote. ArcelorMittal employees received a package similar to US Steel in exchange for cuts to retiree pension and health care benefits.

USW Local 6787 President Paul Gipson commented in statement after the ratification on the difficulties of the ArcelorMittal negotiations:

“Management did accomplish one objective in this round of talks. The long-term relationship between our union and this multinational giant has been severely damaged. The solidarity that all of you brought to the table from each respective shop, unit, and department at Burns Harbor, including our Gary West Plate, enabled your Bargaining Committee to fend off the most serious attack by a company our union has ever engaged in bargaining with since 1959.”

“Save your money, three years is not that far away,” Gipson concluded. “Realize what you have, recognize who wants to take it away from you. . . . ‘Excellent, good, fair?’ Only fair, for many good reasons.”

A Very Abbreviated History of the USW

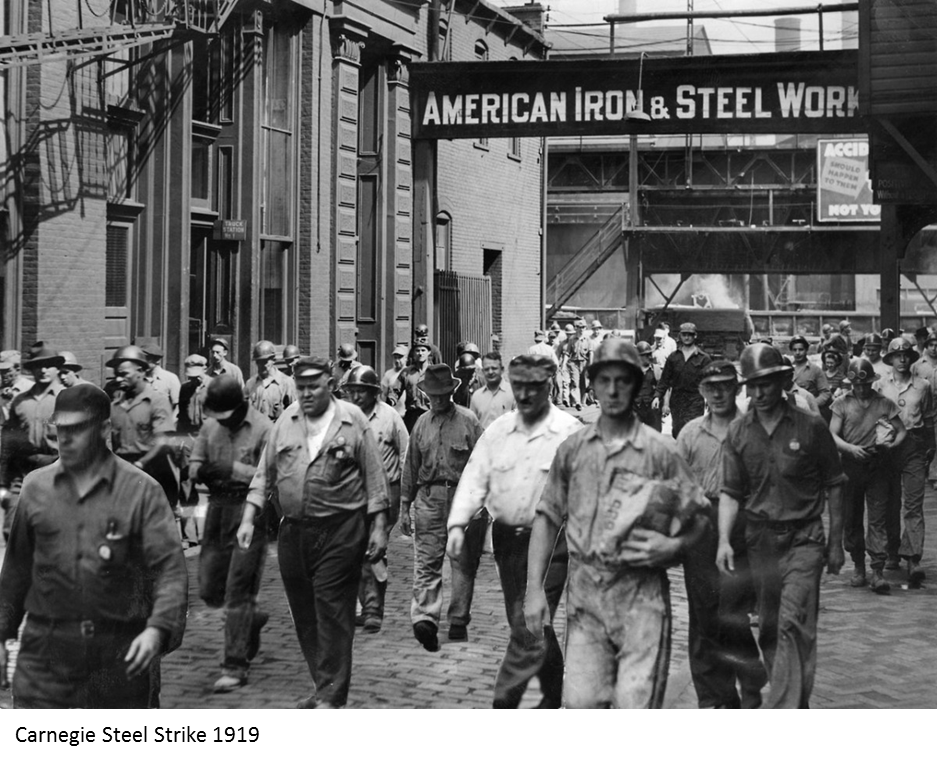

One of the earliest steel strikes occurred following World War I. Workers anxious to improve wages and work conditions mobilized under the American Federation of Labor and in 1919 more than 350,000 steelworkers walked off the job for 14 weeks. The strike was largely a failure due to bickering among the 24 represented unions (including the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers) and resistant steel mill management.

One of the earliest steel strikes occurred following World War I. Workers anxious to improve wages and work conditions mobilized under the American Federation of Labor and in 1919 more than 350,000 steelworkers walked off the job for 14 weeks. The strike was largely a failure due to bickering among the 24 represented unions (including the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers) and resistant steel mill management.

In June 1936, the weakened Amalgamated Association merged with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) form the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC). The first SWOC contract was signed with Carnegie-Illinois Steel (US Steel) for wages of $5 per day and benefits.

SWOC went on to try to organize what was called “Little Steel”– Bethlehem, Republic, Youngstown, National, and Inland—which led to violent resistance from the steel companies. At the beginning of the Great Recession, with steel orders down and tensions high, SWOC members walked off the job in a May 1937 strike that resulted in the “Memorial Day Massacre” at Republic’s South Chicago Mill. During the violence, ten people were killed and many wounded. The strike was a crushing defeat for SWOC.

In 1941, President Roosevelt created the Committee on Fair Employment Practices to investigate complaints and grievances. SWOC filed unfair practice charges against the Little Steel companies which were upheld by the courts. Republic Steel was ordered to rehire 7000 strikers with back pay. By November 1941 SWOC had achieved bargaining rights for all five of the Little Steel companies.

World War II forced unions to accommodate defense needs and, in the aftermath, consolidated union power. The restrictions placed on industry during the war effort increased tension among the workforce that led to a strike wave in 1946. Four and half million workers, spanning industrial America, manned picket lines asking for wage hikes to replace take home pay lost after the war due to reduced overtime, unemployment and higher consumer prices. In the case of U.S. Steel, the company tied wage demands to product price increases.

In 1947 the Taft-Hartley Act was passed in an attempt to balance restrictions on employers, imposed by the Wagner Act, with new restrictions on unions. Among other things, the Taft-Hartley Act allowed states to enact “right to work” laws that outlawed closed union shops. It limited boycotts and strikes and authorized the President to intervene in strikes or potential strikes that may cause a national emergency. Power in the union-management relationship shifted in favor of management. The Taft-Hartley Act, however, became a target for unions which moved the organizations into federal and state politics.

In 1947 the Taft-Hartley Act was passed in an attempt to balance restrictions on employers, imposed by the Wagner Act, with new restrictions on unions. Among other things, the Taft-Hartley Act allowed states to enact “right to work” laws that outlawed closed union shops. It limited boycotts and strikes and authorized the President to intervene in strikes or potential strikes that may cause a national emergency. Power in the union-management relationship shifted in favor of management. The Taft-Hartley Act, however, became a target for unions which moved the organizations into federal and state politics.

In the 1940s SWOC was reorganized into the United Steel Workers of America and spread to Canada. The first company-funded pension plan was won for workers in a contract with Bethlehem Steel in 1949. Between 1945 and 1959 steelworkers walked out five times. The strike in 1952, during the Korean War, led President Harry Truman to seize control of the nation’s steel mills.

The next major steel strike by the USWA occurred in 1959 during a golden period for the steel industry. At issue was a contract clause management wanted removed that limited the companies’ ability to change the number of workers assigned to a task or to introduce new work rules or machinery that would result in reduced hours or employees. The strike, beginning July 16, lasted 116 days and involved 500,000 workers and idled nearly every mill in the U.S.

With no end in sight and steel companies unwilling to capitulate, President Eisenhower invoked the Taft-Hartley act ordering the union members back to work. The union challenged the constitutionality of the Act but it was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. A work slowdown resulted and a final offer by management, required by the Taft-Hartley Act, was rejected by the membership. Vice President Nixon intervened and threatened withdrawal of support for the steel industry by both Democrats and Republicans if a continued strike elicited an election year recession. The union was able to keep the clause, won a small pay raise, an automatic cost of living adjustment and improved benefits.

The longest steel industry work stoppage in the U.S. began on August 1, 1986 when union members of United States Steel walked off the job and did not return until contract ratification on January 31, 1987. The work stoppage was characterized as a strike by employees and a lockout by the company which had prepared shutdown procedures ahead of time in anticipation of a stoppage. A compromise was finally reached in January of 1987 that restricted subcontracting and expanded early retirement benefits in exchange for wage concessions and elimination of 1300 union jobs. Shortly after an agreement was reached, US Steel announced that four plants would be closed permanently, eliminating another 3,500 union jobs.

Steel Industry in the New Millennium

Steel industry strikes in the U.S. have been mostly nonexistent in recent memory. Management and union are more likely to trade negative commentary rather than resort to actually shutting down production. This year’s contract talks, however, come at a time when imports have put a major dent in production and domestic demand. Both ArcelorMittal and US Steel have been working for the past year to trim costs which has led to closures and temporary layoffs.

The USW is well aware of the challenges to the steel industry both domestically and globally and has been supportive of trade legislation to deal with the onslaught of unfairly priced imports. But when it comes to the bottom line, it is difficult to make cuts in pay or, even more sensitive, health care and retirement benefits.

“Our goal this summer is to get a labor agreement, but not at any cost,” said USW Bargaining Committee Chairman Tom Conway. “We are coming together at a difficult time – there is no denying that. But there’s also no denying that we’ve been through situations like this before. We will get through this together. Solidarity and communication will be the keys.”

Strikes and lockouts still serve as a tool to force negotiations. The recent the oil refinery strike is evidence. US Steel, before the bankruptcy of its Canadian assets, used work stoppages in Lake Erie and Hamilton Works negotiations.

What Effect Would a Strike Have on the Industry?

There has been much discussion on how a strike, or possibly a lockout, would affect the steel industry right now. There has been some evidence of inventory build-up, just in case a labor situation develops.

A blog entry last week at Platts suggested that a supply disruption would not necessarily be a negative thing.

“That’s because the market has been mostly down or flat this year and with demand being lackluster, market players are looking for any help they could get, including a work stoppage that could tighten supply and raise prices,” said the blogger.

The situation becomes even more complicated when you factor in recent trade cases (and potential new ones) that could reduce the volume of imports (another reason to stock up on inventory). And then, add in the automotive labor negotiations that are currently underway. Any one of these factors could affect demand and production. Occurring all at the same time, it could be disastrous as demand falls off, prices fall and inventory build-up languishes in warehouses.

SMU opinion is there are no winners when there is labor unrest and lack of trust between the union and management. Short term inventory gains, as suggested by the Platts blogger, quickly turn into a mess once the disruption has dissipated. A strike or lockout would also invite more foreign steel into the market (and what does it do to any existing antidumping suits?). It also puts a wedge in between the affected mills and their customers.

Labor negotiations will be a vital subject to follow for the next several months leading up to our 5th Steel Summit Conference in Atlanta which just happens to begin on September 1st…