AMU

February 6, 2026

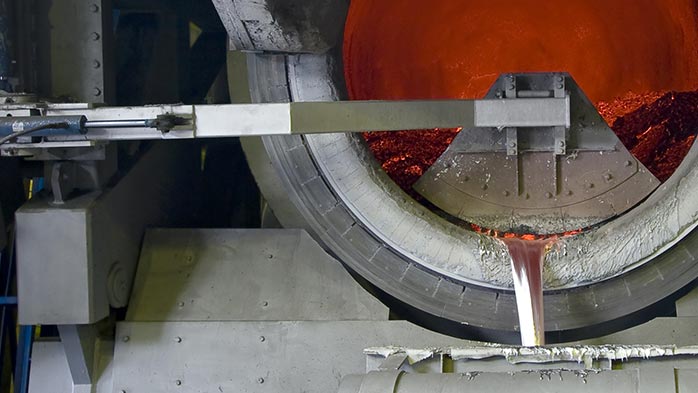

Century's Hawesville smelter sale in the context of US primary aluminum

Written by Nicholas Bell

Century Aluminum’s sale of its idled Hawesville, Ky., smelter site marks another milestone for the US primary aluminum industry, coming amid heightened trade protections and ongoing constraints tied to electricity costs.

The company said the former smelter will be redeveloped by TeraWulf into a digital infrastructure campus supporting high-performance computing and artificial intelligence (AI). Century will retain a non-controlling minority equity stake in the project.

Hawesville had been Century’s largest US smelter and the largest domestic producer of military-grade primary aluminum in North America.

The sale comes at a time when tariffs on imported aluminum are at their most restrictive level under Section 232, and when access to competitively priced electricity is constraining domestic production.

Idling Hawesville

Century idled Hawesville in June 2022, citing soaring electricity prices driven by the global energy crisis following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Power costs at the site had more than tripled relative to historical norms, rendering continued operation uneconomic despite the smelter’s strong operating performance and strategic importance.

At the time, the company said the curtailment would last 9-12 months. It waited for energy prices to return to normal levels. But that never happened.

Hawesville bought market-priced electricity through an arrangement tied to Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) pricing, a mechanism for determining power transmission costs, exposing it directly to wholesale power volatility. MISO’s grid covers the parts of the midwestern and southern US and parts of Canada.

According to CRU Group’s data, power prices at Hawesville reached the upper-70¢ per megawatt-hour (MWh) when the site was idled. The levels exceeded those at Magnitude 7 Metals’ New Madrid, Mo., smelter by more than 75%, and also curtailed operations. (CRU Group is the parent company of AMU).

While high power costs also hit Century’s Sebree, Ky., and Mt. Holly, S.C., in 2022, Hawesville was the only facility fully idled, reflecting both its scale and its exposure to market-based electricity.

Tariffs, power and restarts

Section 232 tariffs were thought to improve the economics of domestic primary production by raising the costs for imports.

But, the tariffs have coincided with rising electricity pricing.

Century announced plans in 2025 to restart idle capacity at its Mt. Holly smelter. The decision was enabled not by tariffs alone but by the extension of a long-term power agreement with Santee Cooper through 2031.

The company expected planned capacity restart to be reached by June 30, following a $50 million investment to restart the remaining 90 pots. That would lift output to more than 220,000 metric tons per year, close to the plant’s 230,000-metric-ton nameplate capacity and adding an estimate 10% to US primary aluminum production.

That said, even if all remaining US smelters were operating at full capacity, the country would remain dependent on imports for the majority of its primary aluminum needs.

High-purity aluminum capacity and defense uses

The loss of Hawesville carries implications beyond headline tonnage.

The smelter had been the largest domestic source of high-purity primary aluminum used in aerospace and defense applications—arguably falling under the national security rationale of Section 232.

With Hawesville removed from the smelting landscape, the burden of supplying domestically produced, aerospace-grade primary aluminum in commercial quantities has shifted to Arconic.

Arconic’s Davenport plant recently expanded high-purity aluminum capacity, doubling production to more than 40,000 metric tons per year.

While this helps address immediate supply gaps, it does not replace the loss of primary capacity capable of producing defense-critical metal at scale.

According to a 2018 Department of Commerce report, Hawesville had high-purity aluminum production capacity of about 100,000 metric tons per year.

The most recent data on output contained within the report, from 2016, showed production of about 60,000 metric tons. At the start of that year —nearly a decade ago—eight primary smelters were operating in the US, compared with just four today.

The report also noted Century supplemented domestic production with imported, high-purity aluminum from the United Arab Emirates, where Emirates Global Aluminium (EGA) is headquartered, indicating an existing commercial relationship between the two companies.

From smelters to data centers

Hawesville’s redevelopment fits a broader pattern. Former smelter sites have become increasingly attractive to data center developers competing for electricity to support AI.

Alcoa sold its Eastalco smelter site in Maryland in 2021 for redevelopment into a data center campus. More recently, Riot Platforms bought the former Alcoa Rockdale site in Texas and entered into a long-term lease with Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) to support data center operations. Reports from local news outlet Oregon Public Broadcasting indicate Google bought the former Northwest Aluminum smelter complex in The Dalles, Ore., for data-related infrastructure.

Greenfield versus brownfield investment paths

The Hawesville sale also lands amid shifting greenfield ambitions.

Century was selected in 2024 to receive up to $500 million in Department of Energy funding to support construction of a new “green” aluminum smelter in the Ohio or Mississippi River basins.

Since then, EGA advanced plans for a large-scale US smelter in Oklahoma. Century ultimately elected to join that project as a minority partner than pursue a standalone greenfield build.

Under the joint development agreement, EGA will own 60% of the Oklahoma facility, with Century holding 40%.

The project would more than double current US primary aluminum production once completed, but it remains years away from the first metal and is contingent on securing competitive long-term power.

On its most recent earnings call, Alcoa—the other domestic primary aluminum producer—indicated it has no interest in pursuing greenfield investments, citing energy pricing and capital costs. Instead, it is evaluating brownfield opportunities without outlining specific plans.

Looking ahead

The sale of Hawesville does not eliminate existing capacity, as the smelter has been idled for several years. But it does narrow the set of pathways available for restoring domestic primary aluminum production.

As former smelter sites are repurposed for other uses, the number of brownfield assets that could support restarts continues to decline.

At the same time, recent developments highlight how capital-intensive and energy-dependent primary expansion has become.

While greenfield capacity remains under development, those efforts are fewer in number and longer in lead time than earlier expectations suggested.

How those constraints interact with trade policy, energy markets and end-market demand will play a central role in shaping domestic smelting. Expansion appears likely to rely on external capital and technology partnerships rather than a broad revival of independently developed US smelting capacity.