Analysis

February 15, 2026

Leibowitz: Adjustments to Section 232 in the offing?

Written by Lewis Leibowitz

Editor’s note

This is an opinion column. The views in this article are those of an experienced trade attorney on issues of relevance to the steel market. They do not necessarily reflect those of SMU. We welcome you to share your thoughts as well at smu@crugroup.com.

There are two major features to the current tariff debate. First, who pays the tariffs? The Trump administration argues that foreign exporters absorb the cost of the tariffs, while US importers actually write the checks.

Most economists and free traders argue that Americans end up paying them. An endless debate, because some of the tariffs are absorbed by exporters and some are absorbed by Americans, depending on the markets involved.

The second feature is whether manufacturing will return to the US because of the tariffs. The administration says manufacturing will come back, but patience is required. Keep electing us, they imply, and all will be well. Economists are generally of the view that returning manufacturing, after decades of global competition, is much more complex than raising the prices of imports. It is another endless debate.

The tariff controversy exposes contradictions with potentially massive political and economic consequences. The steel and aluminum “derivative” tariffs are a key battleground over these contradictions. But they are hardly the only tariffs that raise these endless debates with no sign of a clear resolution.

Last week, news stories (first reported in the Financial Times) appeared that the Trump administration was working on adjustments to steel and aluminum derivative tariffs. Ostensibly, these tariffs are only imposed on the steel or aluminum “content” of derivative products. But Customs has not provided clear guidance on how to calculate content. Confusion and controversy are running rampant.

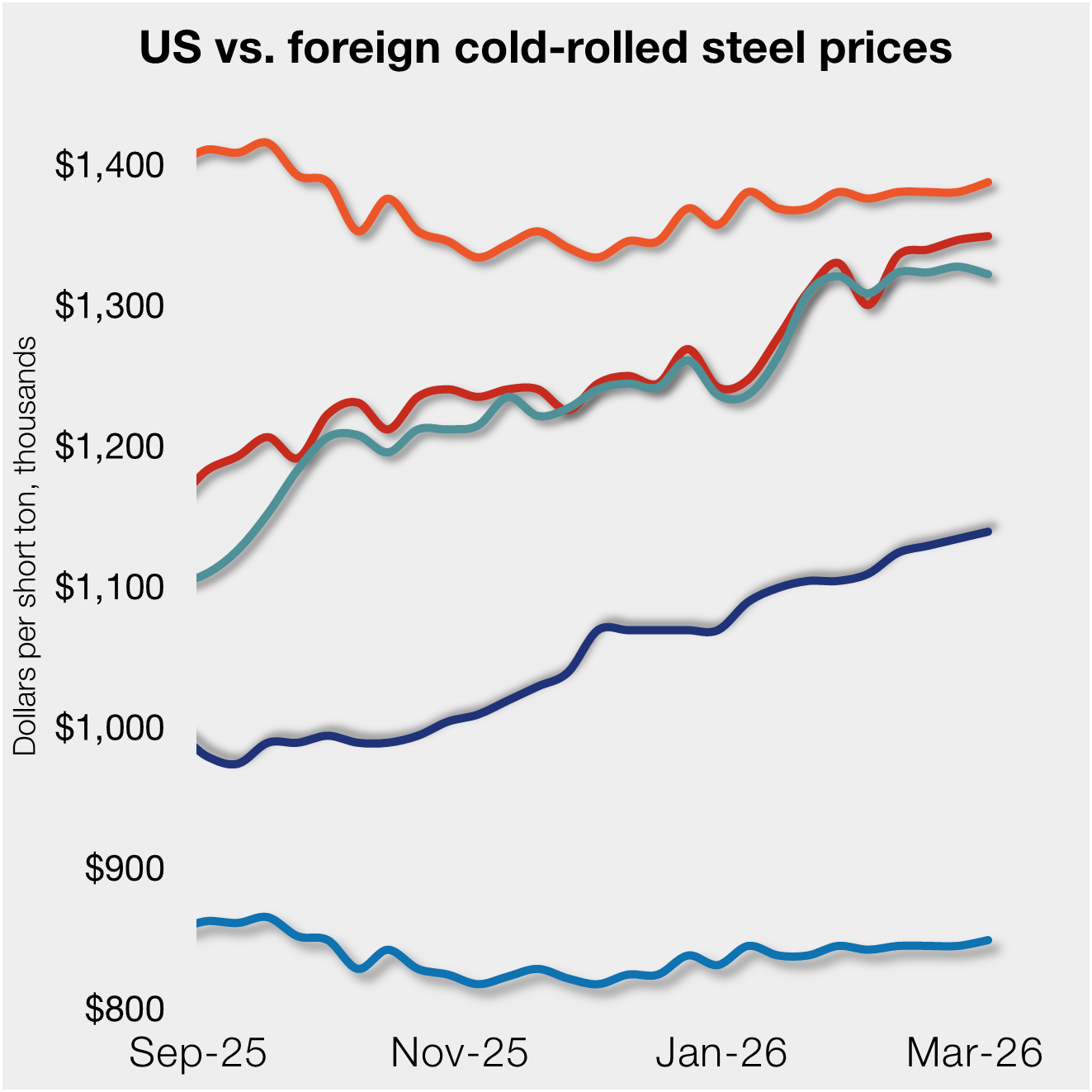

The tariffs contribute to price rises that industries and consumers see every day. Voters are paying attention. Economically, the tariffs affect customer choices that won’t necessarily lead to domestic manufacturing returning to our shores. Administrative problems with derivative tariffs increasingly present problems as well.

Diplomatically, the European Union wants derivative tariffs reduced or eliminated from transatlantic trade. The Trump team has refused to do so, presenting difficult issues affecting the recently announced agreement between the EU and the United States. The endless controversy over who really pays the tariffs will likely impact policy choices and the November midterm elections.

Complex issues and political debates like this interest enterprising reporters. Hence, the stories over the last few days about derivative tariffs.

One complexity is that many separate markets exist for steel and aluminum derivative products. Tariffs will affect these markets in different ways. Imagine a market for a derivative product that has ready substitutes that don’t require steel or aluminum (like adhesives). Customers will find those substitutes, and domestic production of steel or aluminum won’t increase.

For markets where no ready substitutes for steel or aluminum exist, foreign exporters could absorb a portion of the tariffs through price reductions. If that hurts them financially, they could get government support to tide them over. If that happens, prices in the US won’t increase so much, and domestic manufacturing won’t increase. In short, tariffs on steel and aluminum derivative products probably won’t bring as much reshoring as their proponents predict.

In response, the US could subsidize manufacturing to support new competitors. But, as I’ve written before, that medicine needs to be used sparingly. Sectors with a bright future that are growing long term (such as electrical steel) might be good candidates. But most existing industries either don’t need help or won’t benefit from it long term. Propping up declining industries with subsidies is a losing proposition.

The new rumors stem from several problems with tariffs. Who pays them is one. But, as we’ve seen, whether foreigners or Americans absorb the increased costs of the tariffs does not affect whether tariffs will cause manufacturing to come back to the United States.

Another problem is the administrative problem of calculating the value of steel and aluminum content of imports. Only the steel and aluminum content is subject to the Section 232 derivative tariffs under the president’s orders. Customs has proven unable to give reliable guidance on how those calculations should be done. There is already litigation on the issue, with a lot more to come. In short, administration of the derivative tariffs is a mess.

Then there is the debate about how (or even whether) derivative tariffs will stimulate domestic production. That is very difficult because there are literally thousands of product markets that may have very different outcomes. In general, the influence on reshoring is highly debatable. The negative effect on consuming industries and individual consumers is not.

Politics will certainly play a role in these endless debates. Rising prices for steel and aluminum cans, pie plates, and other consumer items will affect attitude of voters in the primaries and in November. If Congress turns Democratic in November, the situation in Washington could change dramatically. The administration could be facing impeachments of President Trump and several Cabinet officials, for example. If Congress passes laws, the president can veto them. But the administration will increasingly be on the defensive.

In short, the stakes are very high when it comes to tariff policy. The derivative products issue is only a part of that debate. The public relations efforts to influence policy and the attitudes of voters are increasing. The American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI), for example, issued a press release on Friday generally defending steel tariffs and suggesting steel producers are worried about the future of the tariffs more broadly.

It is far too early to conclude that the tariff structure is in jeopardy. Indeed, tariffs are at the center of President Trump’s philosophy. While there may be disagreements within the administration about tariffs, there is no sign that any senior official advocates eliminating or sharply lowering them. Anyone who did so could soon need Indeed® to find a new job.

For those of us outside the administration, the major problems associated with these Smoot-Hawley level tariffs will continue to rankle. Unlike the current debate, the results of those earlier tariffs nearly a century ago are clear, and not good.

The administration has started to appreciate the major problems that steel, aluminum, and other industrial users of tariffed products face. Those problems threaten job losses vastly exceeding any near-term gains. The forces set loose by tariffs, unfortunately, do not seem likely to produce major job gains over the longer term.

That debate will continue and will be affected by the courts and the voters over the next several months.