Analysis

January 15, 2021

CRU: Auto Industry Acceleration Delayed While the Chips are Down

Written by Ippolito Tarabini

By CRU Economist Ippolito Tarabini and Multi-Commodity Analyst Zanna Aleksahhina, from CRU’s Steel Sheet Products Monitor

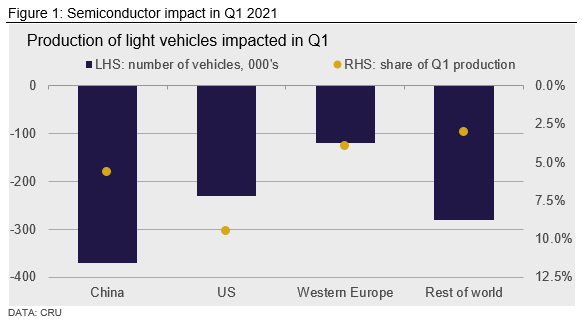

There is a global semiconductor shortage. It was ignited by strong demand for consumer electronics during the COVID-19 pandemic and it is now threatening auto production around the world. We expect it to reduce global vehicle output by around one million units in Q1, constraining production mainly in China, the U.S. and Western Europe. But once resolved in the second half of the year, we see the auto industry finally accelerating.

H1 Production Takes a Hit Due to Semiconductor Shortage

A global semiconductor shortage, which started due to strong demand for consumer electronics (PCs, TVs, gaming consoles, etc.) during the COVID-19 pandemic, is now threatening vehicle production around the world. Semiconductor chips are usually included in the vehicle infotainment systems, brakes, and power steering. Electric vehicles—which are growing in popularity—require a greater amount of chips than petrol or diesel vehicles.

The auto industry is dominated by complex just-in-time supply chains, so it is very vulnerable to supply disruptions. This was illustrated in early 2020 as disruptions caused by the pandemic shut down production lines across the world. The current shortage is especially disruptive for the USMCA bloc, due to its low inventory levels. Several car makers such as GM, FCA, Ford, Volkswagen and Honda have announced temporary factory closures in 1Q 2021 across the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. However, not all car makers are confronted with such an obstacle. Toyota has avoided the problem by stockpiling.

The current chip shortage has been exacerbated by former President Trump’s U.S.-China trade restrictions. Restrictions were placed on Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), a major factory in China, which meant that customers redirected their orders to other large global chipmakers such as Taiwan (China)-based Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC) and South Korea-based Samsung and SK Hynix. These companies account for most of the world supply. Given that the automotive industry represents only around 10% of the chip market, and is often a more volatile customer, semiconductor producers have prioritized their supply for tech companies, with important repercussions for the auto sector.

Though the shortage originally started affecting manufacturers in India and China at the end of 2020, the reliance of the world on chip production capacity in East Asia means automotive Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) are being affected globally. Although the situation is still developing, we expect that approximately 1 million units will be impacted by the semiconductor shortage in Q1; around 370,000 units in China, 230,000 in the U.S., 120,000 in Western Europe and the remaining 280,000 units in the rest of the world. To put things into perspective, 1 million units is only a fraction of the total 14 million units of production that were lost during the start of the pandemic in 1H 2020 and is only around 1-1.5% of global yearly output. The adoption of new emissions standards through the Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP) in 2018 was more disruptive for the industry.

We expect the disruptions to be temporary; as lockdowns ease, so should demand for consumer electronics. In some cases, OEMs may need to pay more for chips, but they should ultimately get the supply they need to produce the vehicles consumers want. We believe much of the lost production will be recouped in H2 2021, as the demand for cars will still be there.

In the longer-term, OEMs may choose to build up larger stocks of semiconductors to reduce this risk. However, previous episodes of supply disruption (for example the Fukushima disaster in Japan in 2011) have not led to such changes in business models.

Who Needs to Buy a Car?

Although the semiconductor shortage will hamper the auto sector recovery in the near term, there remains considerable potential for global growth in auto sales. For this reason, we now look at how the stock of cars per capita has evolved over time, and across different regions.

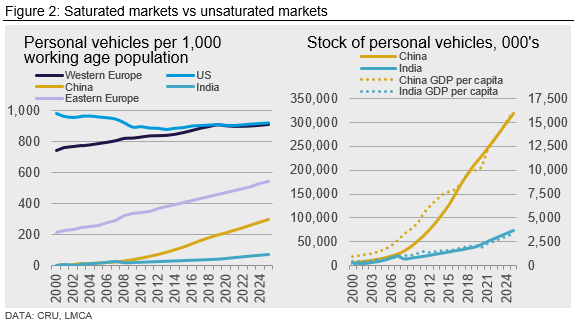

Personal vehicle ownership to flatline in saturated markets, increase in unsaturated ones: In Western Europe (WE) and the U.S., the rate of car ownership is more than four times that of China, and 18 times that of India. This fact is a key pillar of our forecasts—whereas in saturated markets (WE and U.S.) we expect car ownership to remain broadly flat, in unsaturated markets car ownership can still grow at healthy rates. Inevitably then, vehicle production that serves saturated markets will be primarily driven by replacement demand. Ultimately, this means we expect lower growth in WE and the U.S. than we do for China and India.

For unsaturated markets, the increase in the stock of personal vehicles on the road has closely followed GDP per capita. China’s outpacing of India in the stock of personal vehicles from 2007 onwards is matched by a similar faster pace of growth in GDP per capita.

Where do domestically produced cars go? Vehicles produced in China, U.S., and Western Europe differ greatly in the markets they serve. Only 4% of vehicles manufactured in China are exported, whereas almost 20% of WE vehicles are shipped to non-WE destinations. The U.S. is somewhat in between. Clearly this has important implications—while China’s car industry can boom thanks to domestic consumers alone, the same is not true for the European one. However, WE OEMs can cope better with weaker internal demand, as strong demand from abroad can compensate them for lost domestic sales. This phenomenon can already be seen in Germany, where January car exports dropped by less than both domestic production and car registrations.

Regional Outlook for Key Markets

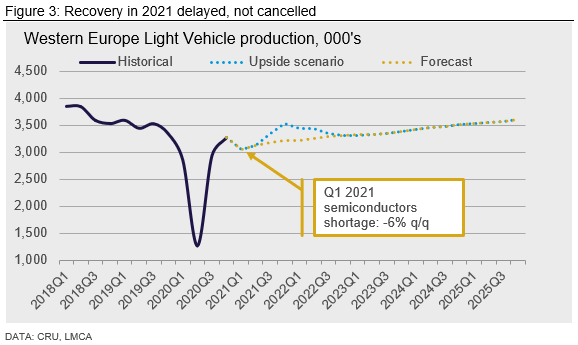

Western Europe—Bumpy 2020 but room to run in 2021: Light vehicle production in Western Europe dropped by ~26% in 2020, even more than during the GFC. However, output recovered strongly in late 2020, and we expect 2021 to record a strong annual growth rate, albeit not strong enough to return to 2019 output levels. While the short-term outlook is clouded by extended lockdowns and the semiconductor shortage, our view is that the WE auto recovery is delayed, not cancelled.

As economies re-open thanks to a combination of previous lockdowns and vaccinations of the most vulnerable age groups, the release of pent-up demand should drive the recovery in both sales and production. In fact, we see the potential for an upside surprise in WE Light Vehicle (LV) production in the second half of the year, inverting the disappointing trend of last few years. Firstly, the combination of high savings rate and vaccine-induced optimism make it more likely for consumers to feel more comfortable purchasing a new vehicle. Generous government incentives targeting EVs in some countries, including Germany, France, UK and Netherlands, could certainly support that. Moreover, an aging vehicle fleet (the average age of passenger cars is currently at 11.5 years, up from 10.8 in 2018) suggests that replacement demand could also play an important role.

If vehicle production between mid-2021 and mid-2022 was to return to 2019 levels (a useful benchmark in that before 2020, it was the worst year in a decade), approximately 1 million extra vehicles would be produced, and annual growth would be 27%.

Even though 2020 was overall a terrible year for European OEMs, there was a bright, or rather green, spot: electric vehicles. Thanks to generous government incentives, demand for EVs surged, increasing from 3% of car registrations in 2019 to 10.5% in 2020. While some of the strength is bound to come off as the incentives will be less generous in 2021, the responsiveness of European consumers to government schemes suggests Europeans have not fallen out of love with cars. Norway has shown the way here, with EVs now accounting for more than 50% of sales of new cars. Falling battery costs could also boost adoption. Some analysts now predict that in the next few years EVs will achieve parity with ICE vehicles in like-for-like upfront cost.

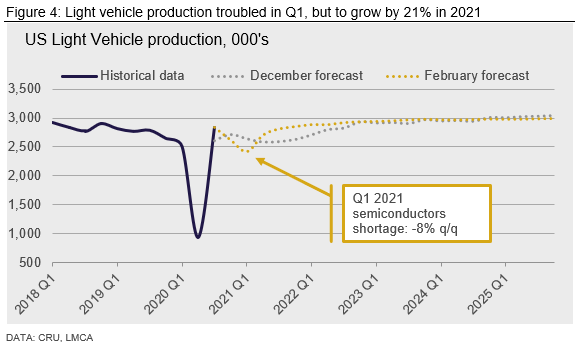

The semiconductor shortage should only be a hiccup in the U.S.: We expect U.S. light vehicle production to grow by 21% in 2021 although the current shortage of semiconductors has led us to cut our forecast by 9% in Q1 2021 from our December estimate (Figure 4). As a result of the global chip shortage, at least six OEMs have announced a cut in production causing an estimated loss of around 230,000 units in Q1 2021. The automotive sector should recover in H2 2021 supported by fiscal stimulus and higher demand, provided the semiconductor shortage does not extend for longer. An upside risk we see for the U..S auto industry is the potential for the Biden administration to push an aggressive green agenda—for example, the widespread adoption of BEVs for the federal fleet.

China: Amber light for chips shortage, green for EVs: 2021 will be a good year for China’s auto industry, after seeing its strong recovery from the COVID-19 crisis in H2 2020. We forecast growth for auto production of 7.8% y/y in 2021, and annual output of 27.2 M units. In the short term, the current semiconductor shortage is expected to cause about 370,000 units’ loss of production in Q1, which will be mostly made up in the rest of the year.

Electric vehicles will remain a hot topic this year in the Chinese auto industry. Altogether with the government stimulus and the change of regulations, we expect to see 2.1 M EVs sold in China in 2021, growing 23% y/y. Like in much of the world, upside risks in China are linked to a faster penetration rate of EVs, which we currently expect to reach ~20% by 2025, from 7% in 2021.

Implication for Commodities

We expect 2021 to be the year of recovery for the global automotive industry, where the three biggest markets—China, Western Europe, and the U.S.—all record strong growth rates thanks to renewed consumer demand and an improving macroeconomic backdrop. As a key global consumer of steel, aluminum, copper, and battery metals, expanding automotive production (albeit from a very low base) will help support commodities demand throughout the year.

So far there are few signs that the semiconductor shortage is affecting metal demand. This may be because OEMs expect it to be temporary, and still want metal stocks to produce later in the year. For example, impact on aluminum demand has been limited because the shortage has had less of an impact on premium brands, which are the most aluminum intensive, such as EVs. However, if production faces longer-lasting disruption, it is likely this will feed through to demand for metal products.

Overall, while the automotive sector will suffer in the near term, our view is that in 2021 the auto industry will shift up a gear—or perhaps two.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com