Market Data

September 30, 2022

CRU Economics: The Bad News Keeps Coming

Written by Alex Tuckett

By CRU Principal Economist Alex Tuckett, from CRU’s Global Economic Outlook

September has reminded us how risky the current global environment is. Stubbornly high inflation, rapidly tightening monetary policy, tight energy markets, and a surging dollar are taking their toll on growth. And the more bad news keeps materializing.

In eastern Europe, Russia’s partial mobilization has increased the likelihood that the conflict in Ukraine will be a long one. Imminent accession of parts of Ukraine into Russia increases the likelihood of escalation.

A mysterious attack on both Nord Stream natural gas pipelines in the Baltic Sea has raised further questions about energy security in Europe. And a badly misjudged fiscal event in the UK has sent sterling plunging and gilt yields surging. China not only continues to face its own internal problems – the slump in the real estate market and the “zero-Covid” policy – but also faces weakening external demand.

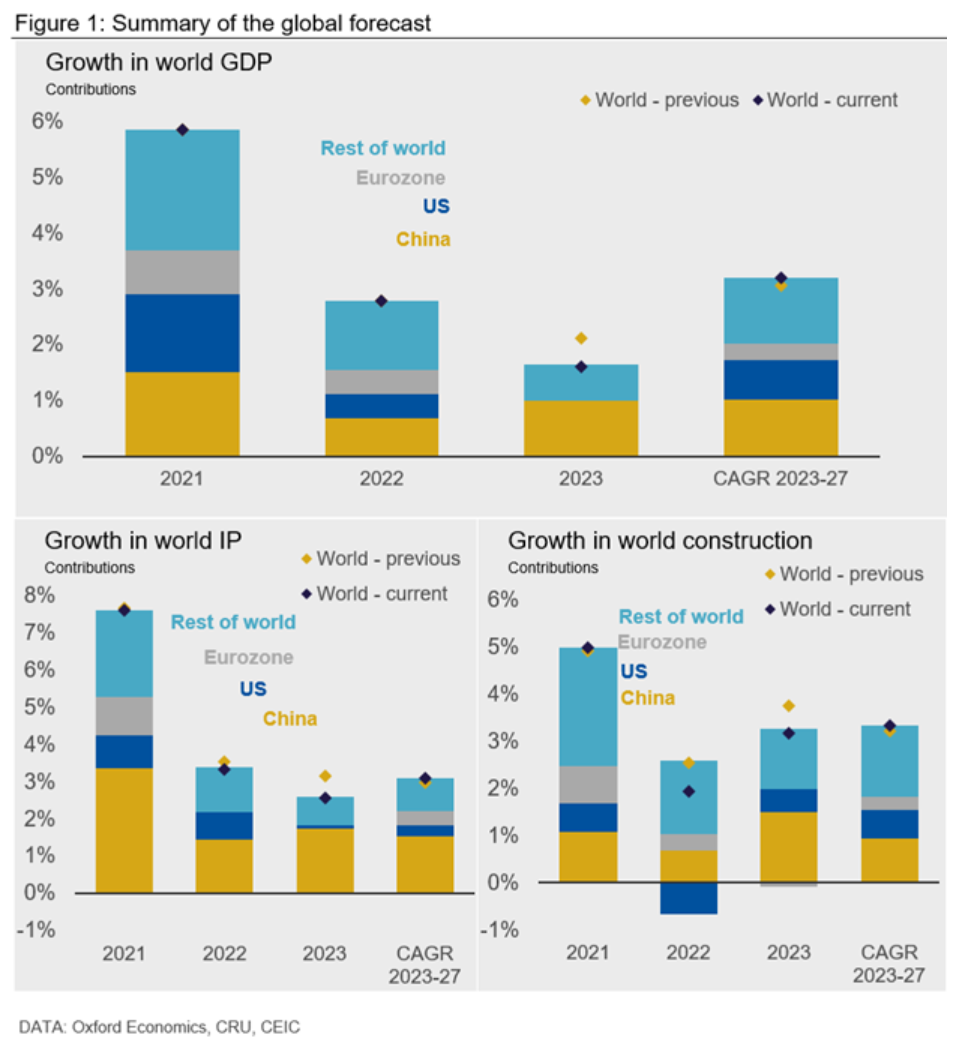

Reflecting these risks, we have further downgraded our forecasts (see Figure 1):

We still expect the world economy to grow by 2.8% in 2022. But we have revised down growth in 2023 to 1.6%, from 2.1% in our August GEO.

We expect global industrial production (IP) to grow by 3.4% in 2022, down from 3.6% in our August GEO. IP growth will slow further to 2.6% in 2023 (down from 3.2% in August).

We expect construction output to grow at just 1.9% in 2022, down from 2.6% in the August GEO. Growth in 2023 will pick up, but only to 3.2% (compared to the 3.8% we expected in August).

Currently, we expect growth to be weaker in the US this year (at 1.7%) than in either the Eurozone (2.9%) or China (3.6%). This may be surprising, given that Europe is at the epicenter of the energy crisis. Furthermore, we believe Europe has entered recession in 2022 Q3 (compared to 2023 Q1 forecasted for the US), and we expect the Eurozone recession to be deeper, with a peak-to-trough fall of 1.3% (against just 0.6% in the US). However, growth in 2022 H1 has already baked in a big effect on annual numbers.

The published data for the US showed GDP falling quarter-on-quarter in both Q1 and Q2 (by -0.4% and -0.1%). This did not fit with other economic indicators, such as the labor market or business surveys.

From a spending point of view, the contraction was driven by a fall in inventories and a wider (real) trade deficit. These are both erratic components of GDP, and inventories are notoriously difficult to measure and prone to revision. However, that is what (for now) the data say.

In contrast, Eurozone GDP proved surprisingly resilient in 2022 H1, growing by 0.7% and 0.8% in Q1 and Q2, as economies re-opened from Covid-19 lockdowns. That strong start to the year will support the annual average growth rate.

More fundamentally, we are making a judgment that macro policy is much more supportive in Europe than in the US. On the fiscal side, unless the Democrats are to hold a majority in both the House and Senate in November’s mid-term elections, there will be little more in the way of fiscal stimulus.

In contrast, this week’s announcement by the German government of a 200 billion euros package to cap power and energy prices for households and firms shows that governments in Europe are willing to deploy considerable fiscal firepower. That will bring its own risks further down the road. Not all countries have the fiscal space that Germany does.

More contentiously, we also believe that domestically generated cost pressures are less persistent in Europe. Although headline inflation (at 10.0%) is now higher than in the US (8.3%), a much bigger proportion is accounted for by energy; core inflation is 5.4% in the Eurozone, compared to 6.3% in the US in August.

The labor market is not as tight and wage growth will be less of a concern, particularly with the economy contracting. This will allow the European Central Bank (ECB) to reverse course more quickly than the Fed, helping the recovery from 2023.

Of course, if we are wrong about this and inflation proves stickier in Europe – for example, because shutdowns in energy-intensive sectors lead to a new supply chain crisis, or because the energy crisis itself proves more persistent – then Europe’s recovery could be much slower.

Figure 1 summarises recent research by the CRU Economics team.

This article was originally published on Sept. 30 by CRU, SMU’s parent company.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com