AMU

May 27, 2025

Wittbecker on Aluminum: Rio Tinto's power move

Written by Greg Wittbecker

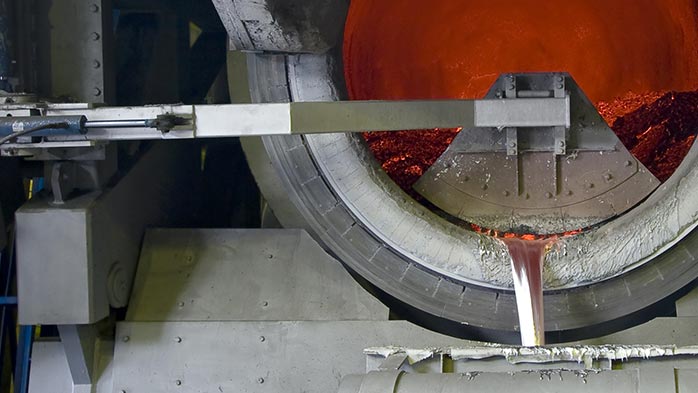

Rio Tinto is embarking on a major upgrade of the nearly century-old Isle-Maligne hydroelectric station in Quebec. A capital expenditure of CA$1.7 billion (US$1.2 billion) will be spent to secure low-carbon power for its aluminum smelters in the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region.

The project is projected to take seven years to modernize one of Canada’s oldest hydropower assets to sustain what Rio-Tinto calls some of the world’s lowest-carbon aluminum production.

The project will replace eight of the station’s 12 turbine alternator units, rehabilitate the water intakes and hydraulic passages, construct new facilities, and upgrade a wide array of electrical and mechanical systems. The overhaul will also modify Isle-Maligne’s spillway so it can be used reliably in winter.

Global engineering firm AtkinsRéalis (formerly SNC-Lavalin) has been awarded a seven-year contract to manage the refurbishment, aimed at significantly extending the plant’s operating life.

The dam that built Canadian aluminum

Commissioned in 1926, the Isle-Maligne dam was the world’s largest hydropower facility of its time. Its construction enabled a boom in regional industry and fed the Arvida aluminum smelter that turned Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean into Canada’s aluminum heartland. The plant’s initial eight turbines were expanded to 12 by the WWII-era, expanding alongside the Shipsaw dam further downriver.

Now Rio Tinto is reinvesting into the legacy asset on an unprecedented scale. The company says it’s the largest hydropower investment since the 1950s – and will in fact involve complete mechanical and electrical system modernization.

Not just Rio’s revival

Rio Tinto’s seven hydropower plants in Quebec are what give its Canadian smelters a competitive, ultra-low-emission profile. The company is not the only one to announce refurbishment plans.

Norsk Hydro has launched a review of major upgrades to its own early-1900’s hydropower station at Rjukan, Norway. Hydro’s proposed project would add pumped-storage capacity and increase peak output to 750 MW.

It’s a similar logic to Rio’s Quebec investment: spend capital now to show up zero-carbon energy for long-term aluminum production.

Certifiably clean

Massive investments in renewable power also feed into the debate over “green aluminum” price premiums.

Some metal buyers have been reluctant to pay extra for low-carbon aluminum, and current premiums remain modest. Producers, however, argue that such premiums are justified by the costly long-term initiatives required to decarbonize production.

Most certifications depend on carbon emission thresholds, but the labels can differ as to what part of the supply chain they focus on. For instance, some have what is called a mine-to-metal focus, while others focus specifically on the emissions from the smelting process.

In part, it’s about meeting rigorous sustainability benchmarks. For example, the Aluminum Stewardship Initiative (ASI) Performance Standard calls on members to cut greenhouse gas emissions from a lifecycle perspective and to steward water resources responsibly.

US smelters need a socket

The urgency of securing long-term, low-carbon power isn’t theoretical, it’s playing out in the US today. While North America boasts isled smelters capable of producing hundreds of thousands of primary aluminum, the real bottleneck is energy sourcing.

For instance, Century Aluminum’s plan to build the first US smelter in decades hinges on power negotiations to make it viable under current decarbonization goals and possibly subsidy frameworks in addition to the federal grant of up to $500 million from the Department of Energy (DOE).

The company has opted to pursue a new plant entirely instead of restarting its idled Hawesville, Ky., smelter that was shuttered due to soaring energy costs.

One potential roadblock is the reliance of the Ohio-Mississippi River Basins on coal- and natural gas-fired electricity generation, Both regions separately account for about a fifth of total US coal-fired electricity production in the country – a 40% combined output.

Meanwhile, if you move slightly west, Emirates Global Aluminium (EGA) recently announced its own plans to build a smelter in Oklahoma. The company explicitly stated the smelter is contingent upon a “competitive long-term power supply and state and local investment incentives and tax credit arrangement.” It is holding active power procurement talks with the Public Service Company of Oklahoma and the Oklahoma government for a low-carbon power solution to serve future demand. Unlike the Ohio-Mississippi Valley river basins, a significant share of Oklahoma’s power generation comes from wind power.

In both cases, the aluminum isn’t missing… the power is. And the capital to secure it – whether through power purchase agreements, state partnerships, or in Rio’s case, massive refurbishments – is the defining feature of green aluminum competitiveness. Smelters without access to renewable power risk remaining idle, regardless of market demand.

Premiums or backpay?

Rather than estimating a premium on a hypothetical aluminum tonnage tied directly to Isle-Maligne dam, a better way to understand the return on Rio Tinto’s $1.2 billion investment is through avoided energy costs.

With a generation capacity of 463.8 megawatt hours (MWh), an average power consumption of 14.85MWh/t across the five Rio plant’s fed by the dam, and a reasonable efficiency assumption of around 80% with a standard flow rate, that output would roughly support production of about 218,786 metric tons (mt) across the company’s wholly-owned Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean operations.

That said, a green aluminum premium of $20/mt (1¢/lb) would translate to only $4.38 million per year in additional margin, far too small to meaningfully offset the $1.2 billion refurbishment on its own.

The realized gain is in the energy arbitrage.

If Rio were forced to buy that same power from Hydro Quebec third party rate, the cost would be substantial as Hydro Quebec’s exported power averaged $75/MWh in 2024. Even using a more regionally realistic benchmark – $43.45/MWh, the average rate Rio reportedly pays when it co-invests in mills that don’t use its captive power – Bécancour and Alouette, the difference is stark.

Compared to Rio’s internal generation cost of around $7/MWh, that represents avoided costs of $68/MWh and $36.45/MWh, respectively.

At $36.45/MWh avoided, moving forward with the local industrial aluminum smelter proxy, the annual savings on 3.25 million MWh would be $118.5 million, resulting in a payback period of around 10.1 years.

Cost curve or market curve?

From an upstream perspective, Rio’s investment in Isle-Maligne isn’t just about environmental virtue – it’s essential to preserving one of the lowest-cost smelting footprints in the world. The dam secures energy independence, shields the company from market volatility, and keeps emissions near zero.

And while some might argue this reinforces an advantage; others see it as exactly the kind of capital-intensive decarbonization the industry claims to support, lest producers may feel as though they’re expected to absorb long-term capex for environmental performance improvements without a green premium, while competing with dirtier, cheaper inputs.

From a downstream perspective, however, these investments are strategic and, in some cases, inevitable. So, while producer argue that buyers should pay a green premium for low-carbon aluminum, critics might ask if this isn’t just Rio investing in its own competitive edge. The same competitive edge the company has wielded for decades that’s allowed it to keep smelting in North America while others folded or fled overseas?

Whether a green premium is framed as a fair return on those investments or as a market distortion depends on your vantage point. But what’s clear is that true low-carbon aluminum doesn’t happen without someone footing the bill for legacy upgrades and long-term power security.

Whether the gutsy capital commitments justify a premium or exposes a market distortion probably depends on where you sit in the value chain.