Prices

October 21, 2014

Oil and Gas Prices and Rotary Rig Counts (Monthly Analysis)

Written by Peter Wright

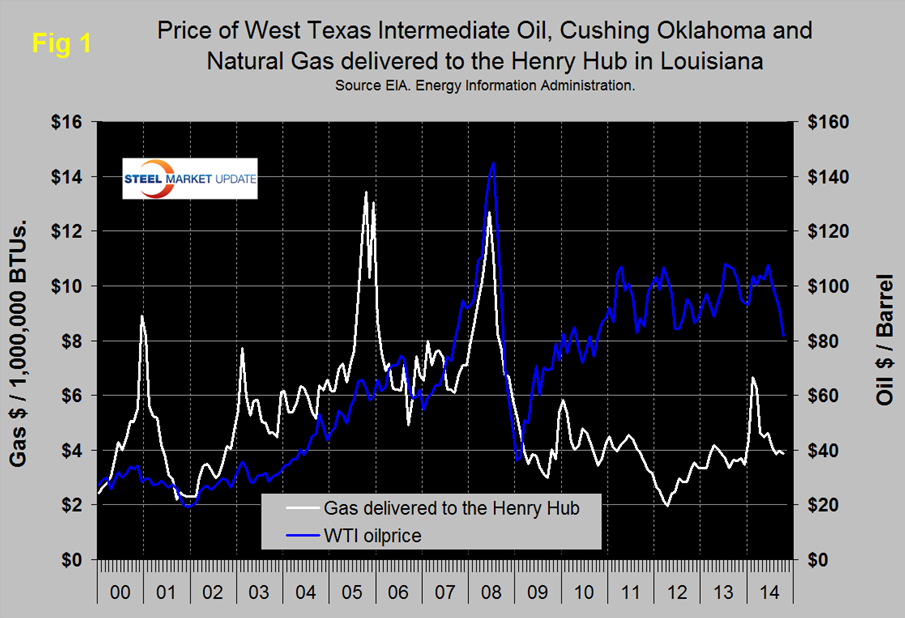

Figure 1 shows historical gas and oil prices since January 2000. The daily spot price of West Texas Intermediate fell below $100 in August and by October 14th was down to $81.72, the latest daily figure available from the Energy Information Administration, (EIA.) Brent closed at $86.36 on the same day. The EIA has calculated that at $80 / barrel only 4 percent of unconventional oil production in the US and only 1 percent of total global output is uneconomic. Natural gas delivered to the Henry Hub in Louisiana fell below $4.00 in August and on October 10th was down to $3.87 / million BTUs.

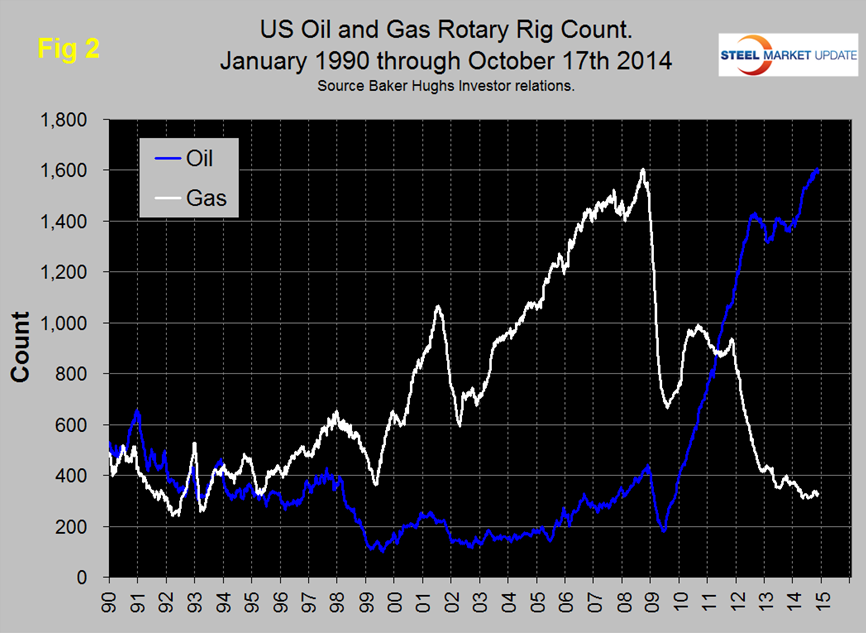

Figure 2 shows the Baker Hughes North American Rotary Rig Count which is a weekly census of the number of drilling rigs actively exploring for or developing oil or natural gas in the United States and Canada. Rigs are considered active from the time they break ground until the time they reach their target depth and may be establishing a new well or sidetracking an existing one. The Baker Hughes Rotary Rig count includes only those rigs that are significant consumers of oilfield services and supplies. Fig 2 shows that the oil rig count which had been trending flat for almost two years has continued to accelerate in 2014 and is now at the highest level in over 2 ½ decades. The gas rig count has trended flat since March and is at a level not seen since the mid-90s.

The total number of operating rigs is now 1,918 a decrease of 13 in the last month. Land rigs decreased by eight in this time frame to 1,861 and off shore by 5 to 57. On a regional basis the big three states for operating rigs are Texas at 896, down by 2 in the last month, Oklahoma at 204, down 11 and North Dakota at 181, down 8. Off shore drilling has now recovered from the Deep Water Horizon oil spill in April 2010 but is still less than half what it was in January 2000.

SMU’s view is that extraordinary changes are presently taking place in the global energy markets that will impact future steel demand. The decline in global oil prices will reduce the incentive to invest in non-traditional exploration and the market trends for natural gas will eventually result in higher prices and a virtuous spiral in production as supply stimulates demand from such industries as power generation and direct reduced iron among many others. Also the restrictions on LNG exports are likely to be relaxed in the face of threats and restrictive actions by Gazprom.

Recognizing the magnitude of current global forces we have included two articles below that we think do a good job of summarizing some of the major influences and actions being planned for global energy production and distribution.

From Zoltan Ban published in Seeking Alpha:

Throughout my coverage of the Ukraine crisis and the economic implications in the region, I often pointed out that one of the end results will be that Russia will one way or another end its reliance on Ukraine as a major transit route for its gas, probably by the end of this decade. The latest news in regards to Russia’s shift towards the East is that both Russia and China are converging on consensus for another gas pipeline in addition to the $400 billion deal they signed a few months back for an East Siberia pipeline with a capacity of 38 billion cubic meters per year (1.2 trillion cubic feet).

The project in question is something both Russia and China have been considering for many years now, but in previous years China’s position was one of dampened enthusiasm for it for various reasons. The proposed project will involve taking gas from West Siberian fields which also provide gas to the EU. The new pipeline to China originally was supposed to cross the border through a region which would have presented many technical challenges due to the rough terrain. The new proposed deal will have the pipeline pass through Mongolia, where the flat plain presents a path that is far easier. Gazprom’s head is suggesting that a deal may be signed by November of this year and while originally the idea was to send 30 billion cubic meters per year, Gazprom is considering raising that capacity to as much as 60-100 billion cubic meters. For reference, about 80 billion cubic meters of gas flow through Ukraine each year, which contributes to 15 percent of total EU gas consumption.

China’s shale gas disappointment, main catalyst of recent deals

As the shale fracking boom took hold in the US, ever more optimistic estimates of global shale gas potential became trendy. Unnoticed by many has been the gradual scaling back of those initial euphoric claims, which were not supported by actual data, as drilling results started to come in. First, there was Poland, where initial estimates of shale gas reserves were cut back by 90 percent. Other places such as Hungary also disappointed. Even in the US, the Marcellus field was downgraded by the USGS from over 400 trillion cubic feet, which is what industry and the EIA assumed to be technically recoverable, to 84 trillion cubic feet. This year it was China’s turn as it had to cut by half its estimate of shale gas production volume by 2020 to 30 bcm per year. China was believed to hold the greatest shale gas reserves on earth.

It certainly does not look like that anymore and this means China needs to re-calculate its energy policy. This is ever more important in light of China’s growing realization that it needs to stop the growth in coal consumption before the damage done to the environment and its population’s health becomes greater than the value of its economic growth and wealth creation. China’s gas consumption was already forecast to reach 400 bcm by 2020, before recent measures such as a new carbon market will be implemented in order to cut emissions. This means that it needs to find over 200 bcm in new supplies, which is more than Russia’s total gas exports to the EU last year. Some of it will probably come from increased domestic production, but I think most of it will have to come from imports. China certainly does not want to lose its competitive edge in manufacturing, so cheaper Russian gas is an enticing alternative to LNG, which is China’s other significant choice.

Russia’s Position

It is by no means a great secret that Russia was always mindful of the potential threat an economically surging China poses to its Eastern borders. China is unlikely to try an outright invasion of Siberia, but among other things, there is an influx of Chinese migrants moving into the sparsely populated and resource-rich region of Eastern Russia. It is possible that down the line, this may lead to internal difficulties for Russia. At the same time, however, Russia needs to sell its surplus gas production, and for the past decade or so its relationship with its main gas customer, namely the EU, has been hampered by Ukraine and its transit country status. In 2004 and 2009 Ukraine’s inability to pay its gas bills led to a shutoff of gas, which then led to Ukraine siphoning the transiting gas for its own needs. That in turn forced Russia to shut off the pipeline completely, leaving many of its EU customers disgruntled. Oddly, many voices blamed Russia for the problem.

Now the relationship with the EU has become even more complicated due to the Ukraine situation. Ukraine is now in a worse economic shape than ever and it just lost its gas discount it previously received from Russia. A best-case scenario is if it will manage to pay its $5 billion debt to Gazprom and then it makes a deal to receive Russian gas at the average EU market price of $385, versus the $268 it enjoyed while relations with Russia were good. Even in such a scenario, it will be unable to pay for its gas bills, which will lead to continued aggravation of the EU-Russia relationship.

Russia has been eager to build the South Stream pipeline in order to do away with Ukraine’s role as a transit country, but due to the current conflict in Ukraine, the EU deemed it wise to object to the continuation of that project, even though Russia already started work on it, and so did Bulgaria. The EU suddenly found it necessary to enforce EU legislation that prohibits the supplier of the gas from also owning the pipelines. The EU was most likely going to do away with enforcing that legislation if it wasn’t for the standoff over Ukraine. After all, Nord Stream did not adhere to the legislation either, yet it was built and is currently operational. Yet, as things stand now, the EU is using anything it can at its disposal to prevent the South Stream project from moving forward, including putting unprecedented pressure on Bulgaria to stop working on the pipeline. Last week, the EU parliament also passed a resolution calling on EU countries involved in the project to abandon it.

Faced with such hostility to the project, Russia is left with no choice but to try to make a deal with China before the South Stream pipeline project might fall apart. Continuing to rely on Ukraine as a transit country is not only undesirable from a political and business point of view, but also from a technical perspective. Ukraine’s pipeline system was already flagged by the IEA as being in a severe state of disrepair and in need of billions of dollars’ worth of investments to keep it running. Needless to say that no one is willing to invest billions of dollars in infrastructure in such an unstable country.

If a deal will be made as it seems to be likely to happen given great renewed interest from China, as well as eagerness showed by potential transiting country Mongolia, gas will start flowing from the Western Siberian fields towards China most likely before 2019. Depending on the pipeline capacity they will agree on, it is very likely that at that point, gas supplies to EU customers in Central and Southern Europe transiting through Ukraine will cease to flow. It is unlikely that Russia will attempt to supply both customers from the same fields.

This means that South Stream will be scrapped and Ukraine will no longer be a gas transit country, just as Russia wishes, given all the troubles it had. The Nord Stream pipeline which does have spare capacity of about 25 bcm will likely be utilized to a fuller extent. Even so, if we are to add up the roughly 50 bcm gap and the 30 bcm Russia will no longer provide to Ukraine, that is an 80 bcm decline in exports to Europe. If the new West Siberian pipeline to China will have a capacity as great as Gazprom desires, of as much as 100 bcm and we add to that the 38 bcm capacity that is already being built in Eastern Siberia, Russia will still export as much as almost 60 bcm more pipeline gas than it currently does. LNG exports will also increase significantly by then, some of which may actually go to Europe. In conclusion, Russia can potentially replace an increasingly troublesome customer this decade, while still managing to increase its exports.

The EU Position

While there are many EU countries not involved in the South Stream project which seem to think canceling it is a good idea, reality is that there is no alternative being proposed, or even contemplated. It is true that some Azeri gas will probably flow to the EU before the end of this decade, and Cyprus is increasingly looking like it will become a net gas exporter, but the volumes in question do not come close to matching the roughly 50 bcm gap left in Central and Southern Europe, as well as a 30 bcm gap which may have to be filled in Ukraine. Some of the total 80 bcm (2.5 trillion cubic feet) gap can be made up by regional suppliers such as Azerbaijan, Cyprus as well as North Africa, if it will manage to avoid a potential social breakdown by the current surge in Muslim extremism inspired violence that is increasingly causing a destabilization of the region. Even in a best-case scenario, however, the rather large gaping hole in gas supplies that a potential and increasingly likely retreat of Russia from the market will not be closed.

LNG to the Rescue?

LNG projects from Qatar, Australia, US, Russia and other places will likely give gas importers plenty of opportunities to source non-pipeline delivered supplies. In some respects, it may seem a preferable solution to pipeline imports due to its more flexible nature. LNG may not be the ideal candidate for the Central Europe region, however, because the economies there are rather fragile, thus not ready to deal with higher energy prices. Russia has been delivering natural gas to the region for an average price of about $400 per thousand cubic meters ($12.5 per thousand cubic feet). Of all the installed LNG capacity the EU already has of some 190 bcm, only a small fraction is currently in use, precisely because of the higher cost compared to pipeline imports.

The current course of events may end up being very bad news for current LNG project developers, because they have been gearing up to meet the surge in demand from places like China. But with China increasingly turning to Russian supplies, LNG producers may be forced to try to market their gas to the fragile Central European countries, where there is very low tolerance for higher energy costs. If need be, those countries will turn to other sources of energy, such as coal or nuclear. Just a few months back, Hungary signed a deal worth about $13 billion with Russia’s Rosatom to expand the current nuclear power plant by 2,400 MW. Given the fragile state of the economies in the region, demand destruction due to higher prices than the Russians had on offer will be a factor that will decrease demand for more expensive LNG.

This all adds up to LNG projects, especially in the US being squeezed from three different directions. US natural gas prices will likely trend up significantly as the higher price will be needed to keep the shale drilling industry going, as well as due to the LNG export facilities creating extra demand. At the same time, capital costs involved in building these facilities have skyrocketed in recent years, with costs per volume capacity tripled. Some older estimates of the added cost of LNG natural gas over the US spot price were in the $3.50 range. With recent price increases in capital costs, that figure might be in the $5 range. This means that if the US natural gas spot price were to go to $8, which is not unreasonable, and likely to be needed to keep shale gas drilling alive, LNG producers will be unable to sell into the EU market, because at that price, customers will switch to other alternatives. In effect, the closer Russia-China relationship on energy is likely to cut into global LNG market growth.

As much as 18 Bcf/d of potential capacity is being either built or planned in the US. There is a long list of investors already in the advanced stage of construction or in the process of getting the needed approvals to start the project.

There is a lot at stake for these companies, given the tens of billions of dollars involved in building these projects. For instance, the Exxon Mobil project in the Sabine Pass in Texas is estimated to cost over $10 billion for a 2 Bcf/d capacity facility. Cheniere reportedly has plans for as much as 5.5 Bcf/d capacity for an estimated cost of over $30 billion. Sempra Energy plans to build a 1.8 Bcf/d facility for about $10 billion. Other companies that are in various stages of planning or building include; Southern LNG, Southern Union, Dominion. At an average cost of about $6-7 billion per 1 Bcf/d export capacity, it is likely that if all the current plans to build LNG facilities will materialize, we are looking at about 18 Bcf/d (200 bcm/year) capacity, at a cost of roughly $120 billion. This may even be a very conservative estimate as the capital cost overrun news keep coming in for projects already in the development phase. With potential LNG markets probably moving away from Asia and going to Europe as a result of Russia’s desire to shift its market due to the Ukraine issue, those who already committed or will commit to these projects in the near future may find themselves dependent on a very price-sensitive market, therefore can end up getting squeezed in terms of profitability.

The head of Gazprom, Alexei Miller, announced that there may be a deal on a Western Siberia pipeline as soon as November. If it happens, and depending on what the final decision will be on the gas volumes involved, we could be looking at a huge change in the global gas market by the end of this year. It is a development that should be watched very closely.

Three Perspectives on Falling Oil Prices from Global Risk Insights. October 17th.

Russia, Saudi Arabia, and the US will feel the effects of oil prices in radically different ways.

It would be logical to think that the emergence of ISIL would have increased oil prices, but Brent crude oil prices have plummeted since July. Having now traded as low as $83 per barrel, oil is at its lowest price since 2012. The steep decline can be attributed to three trends: surging supply led by US fracking production, stagnating European demand, and a strengthening dollar.

Declining prices could have a negative impact on oil-producing economies around the world, but some have significantly more risk than others. There is no silver lining for an already weak Russian economy, while the US stands to benefit from its strengthening currency. Saudi Arabia’s fate remains largely in its own hands, depending on how much influence it can exert on other OPEC members.

Russia

Of all the major trends driving oil prices to two-year lows – dwindling European demand, a glut of global supply, and a strengthening dollar – not one bodes well for Russia’s economy. These negative effects are only compounding the miserable year Russia is already having, between sanctions from the US and Europe and rapid capital flight. The World Bank projects Russia to only grow 0.5 percent this year, which at this point may be optimistic.

As a result, the ruble has fallen to historic lows against the dollar and euro. To prevent further depreciation the Central Bank of Russia is spending billions – up to $3.2 billion a week – to prop up its currency. As the ruble becomes weaker, Russian consumers’ buying power of foreign goods will deteriorate. This leaves Russia facing a perfect storm of sanctions, decreased import revenue from oil, and decreased buying power of its remaining income.

To add to the grim outlook, 79 percent of Russia’s oil is exported to Europe, with the remaining bound for China. Europe’s economic activity, which is highly correlated with its oil consumption, has stalled even in previously healthy countries such as Germany. If Russia is to return to growth, it will have to find buyers for its oil and gas outside of Europe.

Falling oil revenue will put pressure directly on the Kremlin’s finances. Half of Russia’s government revenue comes from oil and gas. Swings in the price will determine whether Russia will have a deficit in 2015. With sanctions cutting Russia off from many of the largest long-term debt markets, financing the deficit will be difficult. Russia’s budget falls into deficit at oil prices between $100 and $110 per barrel.

United States

The outlook for the US is much better than for Russia. In large part, this is due to the end of quantitative easing and that oil across the globe is traded in dollars. The Federal Reserve is beginning to tighten monetary policy, although it is still far from raising rates, at the time Europe and Japan are loosening. As a result, the Dollar Index has risen 21 percent since July. Since oil is traded in dollars the world over, the US is not exposed to exchange rate risk like Russia is.

Further, the price of oil will naturally fall with a stronger dollar. Around 10 percent of the fall in Brent crude prices since July are likely due to the rallying dollar. Much of the rest of the fall has been precipitated by the fracking boom in North Dakota and Texas.

The rise of fracking (especially in North Dakota, which produced very little oil before 2005) has changed the domain of US energy policy. Energy independence may still be a longshot, but much more realistic than it was ten years ago. The wealth and jobs flowing to North Dakota has also been a game changer: unemployment during the peak of the recession was just 4.2 percent and currently sits at national low of 2.8 percent. The average apartment in Williston, ND, now rents for more than in Manhattan.

The irony of the fracking boom is that it may ultimately cause its own end. For a fracking project to be profitable, the price of oil must be higher than traditional oil projects. The full-cycle breakeven price is about $80 per barrel, which it has been since 2010. Given that many players in Texas and North Dakota have already started to set up new wells, the breakeven price now may be closer to $40. That has led to the acceleration of US production, and ultimately to a record excess stockpile. If the current trend of supply outpacing demand continues, the fracking boom may end itself.

Saudi Arabia

Another emerging risk for the US fracking boom is a price war waged by Saudi Arabia and OPEC. As the largest producer in OPEC, Saudi Arabia has an incentive to throttle oil supply to maximize its own profits. Its costs of production are also much lower than fracking producers. If Saudi Arabia’s oil leaders have the wherewithal, they may be able to produce enough oil in the short term to push many US producers out of the market for the medium term. However, this is complicated by the Saudi’s lack of ability to control the production of Algeria, Angola, Libya, and Nigeria. Faced with the problem of falling prices and exploding US production, a complete reworking of OPEC production guidelines – and the nasty negotiations that would go with it – may now become a pressing issue. This would be the only way to guarantee that Saudi Arabia could coordinate the cartel to its benefit – and the fracking boom’s detriment.