Market Data

October 24, 2014

China’s Economic Statistics Q3 2014

Written by Peter Wright

Statistical data out of China is always questioned for a number of reasons, not least is, “Is the data politically motivated.” Other suspicions arise because China gets their data out faster than any other major economy and the data is never revised.

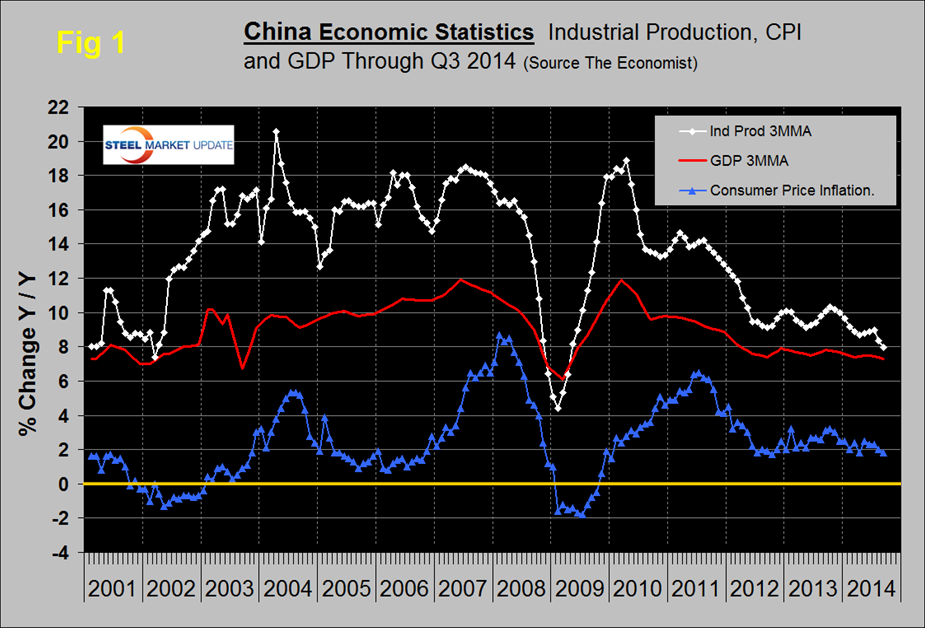

Figure 1 shows published data for the growth of GDP, industrial production and consumer prices through the Q3 of 2014. The GDP and industrial production portions of this graph are three month moving averages. GDP grew 7.3 percent y/y in the third quarter and has been declining since Q1 2010. An increasing number of analysts are now beginning to state publicly that they don’t believe the official economic statistics and the GDP growth is more likely in the 4 percent range. The growth of industrial production year over year increased in September to 8.0 percent from 6.9 percent in August but the three month moving average shown in Figure 1 continued to decline.

Moody’s reported as follows in Economy.com: Industrial output posted its best month-on-month gain in about one year in September, reversing a weak trend from prior months. September’s jump could be driven by electronics and communication products. Auto production continues to increase which is an encouraging sign for domestic demand. The negative news in the report is that the weak housing market is hampering investment, which is dragging on demand for steel, cement and other building products which are awash in overcapacity. Inflation is low and producer prices remain in deflation. The process of reducing this overcapacity through forced closures and mergers is taking much longer than the central government anticipated, and delaying the economy’s transition away from heavy industry. The government, in its accompanying statement, pledges stability in the macro environment, achieved by continued policy fine-tuning.

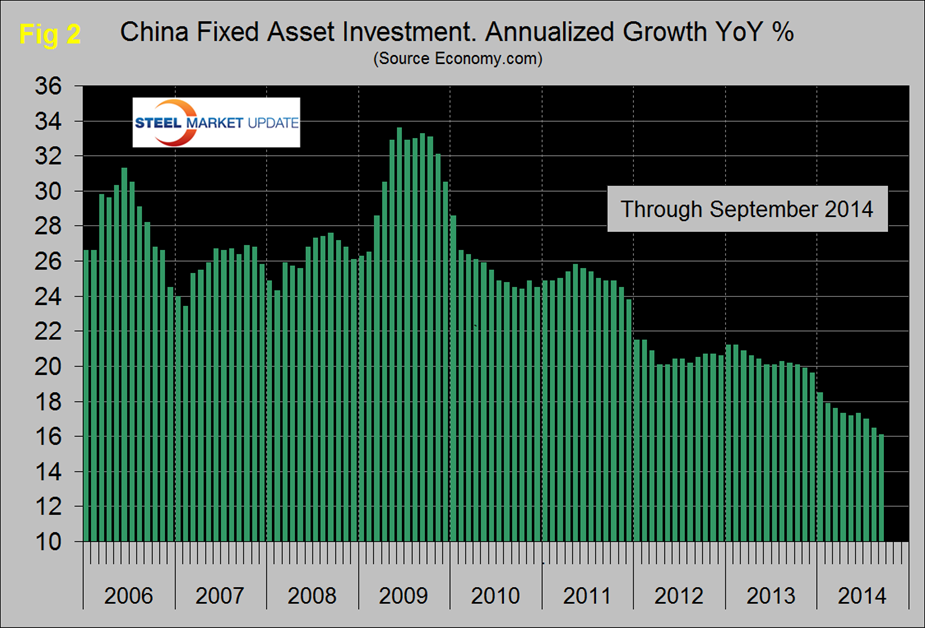

Figure 2 shows the growth of fixed asset investment y/y. The decline experienced in 2013 has accelerated through the first three quarters of 2014. We understand that this data includes real-estate purchases so is not a direct reflection of constructional steel demand. We are assuming that the steel on the ground portion of this data follows the overall trend and this is in line with the stated objective to rebalance the economy in favor of consumer consumption.

Michael Pettis is a professor at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, where he specializes in Chinese financial markets. Last week he wrote the following pessimistic view of the price of iron ore during the rest of this decade:

“I am not sure that what happened last week is proof of anything I’ve been saying, but I do think that the framework I have used over the past decade has been useful, in understanding both the rebalancing process in China and the events that led up to the global crisis of 2007-08. And I think it continues to be useful in judging the adjustment process and why we still have a rough ride ahead of us. This framework has made it relatively easy to make predictions, sometimes “surprising” ones, because by working through the imbalances and assuming that deep imbalances always eventually reverse one way or the other, we can work out logically the various ways in which this rebalancing must take place.

I have argued that since the 2007-08 crisis we have seen some adjustment in the US, very limited adjustment in China or Japan (except to the extent that Beijing under Xi Jinping has stopped imbalances from getting worse), and worsening imbalances in Europe. In a “globalized” world, no country, not even the US, can protect itself from the consequences of imbalances elsewhere. The global economy is a system in which certain types of imbalances are impossible. I especially focus on the requirement that global savings and global investment always balance, but there are others. Because an imbalance at the global level is impossible. If there are imbalances in one country or region, there necessarily must be the opposite imbalances in another, and the more open an economy, the more likely it is to respond to imbalances elsewhere. It is impossible, in other words, to understand any non-autarchic economy in the world except in the context of global imbalances. Three-and-a-half years ago, I gave a dinner speech in Sydney to a group of Australian mining industry investors. In the speech I argued, that the historical precedents, the extent of China’s imbalances, and the growth in Chinese debt made it very clear that China urgently needed to adjust its growth model in a way that would inevitably cause a sharp fall in demand for hard commodities. I stressed that the adjustment was going to be far more difficult than what they were hearing from sell-side analysts, most of who had only just woken up to the realization that there been a great deal of investment misallocation in China.

Australian Iron Ore and Chinese Interest Rates

Once China began the rebalancing process, demand for iron ore had to collapse, and I could say this with full confidence not because I had disc drives filled with data and sophisticated correlation models that proved my case, but simply because this was the logic of the investment-driven growth model, and we had seen this same logic work its way many times before. The powerful opposition rebalancing would necessarily unleash – from groups the Chinese press had dubbed “vested interests” as early as 2007 – always made it unlikely that Beijing would implement significant reforms before 2012. It was only then that the various factions and groups would have agreed among themselves the distribution of responsibilities and privileges of China’s new leadership, including the president and premier, Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang, respectively. It was clear to many economists, especially among Chinese academics, that severe distortions had been building at least since the beginning of the last decade. As early as 2007 Premier Wen openly acknowledged the distortions and imbalances that Chinese growth generated.

As an aside, it seems generally to be the case that the longer an adjustment is constrained, the more likely that the adjustment takes place in the form of what traders call “gapping” – which is a big, discontinuous change instead of a smooth adjustment – so when the change finally took place, the fall in demand (and iron ore prices) would almost certainly occur very quickly, in a matter of two or three years, perhaps. As Rudiger Dornbush said of financial crises, they often take much longer to come than you expected, but then things fall apart much more quickly than you thought they would. This means, to return to iron, if you understood China as a growth “system”, with its own logic, its liquidity channels, its institutional distortions, its balance sheets that embedded pro-cyclical or counter-cyclical tendencies, etc. you would have known that once the process started, rebalancing was going to cause iron ore prices (and prices of other hard commodities) to collapse, and I stressed that I did not think the word “collapse” was overly dramatic. This is because any shift in Chinese demand for iron ore will necessarily be a big shift in total demand. China consumes about 60 percent of global iron ore production, an extraordinarily high share probably unmatched in history except perhaps by England in the mid-18th century. China’s disproportionate demand for iron was clearly the result of its intensely investment-driven growth model. This would change dramatically, I told the guests. I expected that the shift in demand for iron ore generated by rebalancing would cause iron ore prices within 3-4 years to drop by over 50 percent from their then-current levels of around $180-90 a ton.

Rebalancing Demand for Metal

Needless to say my metal price projections, especially for iron ore, were not popular in countries like Australia, Brazil, and Peru. It simply wasn’t possible that any growth rate could keep China consuming 60 percent of total iron ore. That even a small adjustment in Chinese demand, let alone the large one I expected, would cause a big drop in global demand seemed brutally logical.

Early this week I was with an Australian government representative in Beijing and he told me that iron ore prices were currently around $83, and that while some people in Canberra were reluctant to say it too loudly, he and others were increasingly in agreement with my lower forecast of less than $50 well before the end of the decade, in part because supply has come off much more slowly than predicted, but mainly because they now recognize that China’s rebalancing was indeed going to be a far bigger deal for Chinese demand than sell-side research had predicted.

The fact that China’s demand remained so high for so long had created complacency among iron ore producers about China’s ability to continue buying so much iron, but we have to remember that when an adjustment takes longer than expected, the correct interpretation, is not that it is less likely to happen, but rather than when it happens, it will take the form of larger-than-expected gapping. China has only completed the first part of the rebalancing – interest rates, wages and the currency have all moved sharply closer to healthy levels, levels at which the imbalances are no longer getting worse, in other words, but Beijing has still not got its arms around credit growth because to do so would cause GDP growth to drop much more sharply than Beijing is willing to tolerate.

This is the next great challenge for Beijing, and when the regulators finally do start to repair overextended balance sheet, with a much higher debt-to-GDP ratio than any other country at China’s stage of economic development I expect annual GDP growth rates will continue dropping steadily, by 1-2 percentage points a year through the rest of this decade (and there has been increasing talk in the past month or two that GDP growth rates are already 1-2 points below the printed rates). In a recent paper, Larry Summers and Lant Pritchett have suggested that the arithmetic of previous growth miracles implies that China will grow by 3.9 percent on average over the next two decades.

In the case of China, whatever GDP growth turns out to be, Chinese household income growth will be higher and investment growth lower – after nearly thirty years of the reverse relationship – so that the impact of slower growth will be disproportionately smaller on consumption growth and larger on investment growth. This means that lower Chinese growth will not be nearly as painful for Chinese households as we might expect, and that demand for metals will get especially hard hit.

What matters to the Chinese adjustment process, and therefore to iron ore prices, will be how Beijing resolves balance sheets distortions. But when we think about how the Chinese adjustment will affect Australia, we must also consider the impact of savings imbalances globally. The most difficult question to answer for a country like Australia, I think, is whether slower Chinese growth leads to greater Chinese flight-capital outflows, especially when Australia is a favored destination for worried Chinese business owners.

Will the US Ride to the Rescue?

Normally the contraction impact of much weaker iron ore export prices should be partially mitigated by the expansion impact of a weaker Australian dollar, as iron-related inflows drop sharply. If these inflows however are counterbalanced by rising private inflows from Chinese businesses and wealthy individuals taking money out of China, either because of weaker domestic growth prospects of because of rising nervousness and uncertainty, asset prices might not fall as much as we would have expected, but Australia will be caught in a vice a little like that of, for example, Spain, in which export weakness cannot be partially counterbalanced by a weaker currency.

How China, Australia, Brazil, Europe and all the rest will adjust will be determined in part by their debt structures. Thanks to Hyman Minsky’s growing group of followers, we are beginning to remember some of the things we knew about the nasty interplay between debt, overvalued currencies, and unemployment back when John Maynard Keynes, Mariner Eccles and most of all Irving Fischer explained these things to us. I am not completely sure about what Australian balance sheets look like, but I am often told that debt levels in certain sectors (the household sector, for example) are quite high. Higher debt implies a tougher adjustment because as worries about default rise, the debt itself changes the behavior of economic agents in ways that nearly always reduce growth and increase balance sheet fragility. The good news, however, is that Australia tends to have the kinds of institutions (legal, financial, etc.) that reduce the frictional costs of adjustment, so if it is any consolation, they would be worse off if they were a member of the EU.

What I have said about Australia is likely to be even truer about Brazil, although I don’t think Brazilians need to be much worried about a sharp pickup in Chinese flight capital into Brazil. On the contrary, they are likely to see their own flight capital outflows, especially as depreciation pressures increase. Either way all of this creates ugly and self-reinforcing disinflationary dynamics in Australia and in Brazil both of which cases may be hard to shake off without a major US recovery.

But will there be a US recovery? Recent reports about what some are calling the “euroglut” will make a US recovery all the more difficult, perhaps even derailing it, not to mention having a potentially awful impact on China’s adjustment. The “euroglut”, for those who have not followed, is a process described and named by Deutsche Bank strategist George Saravelos. By running large and growing current account surpluses and by forcing their excess savings onto an unwilling world, Europe hoped that it would reduce unemployment at home by taking a bigger share of demand from abroad. Europe is too large simply to assume that the world can absorb large changes in its capital and trade accounts.”

SMU Comment: Hopefully this analysis is overly pessimistic but the US steel industry should be aware that some critical thinkers are projecting further major declines in the price of iron ore and that Chinese steelmakers will increasingly attempt to dispose of their excess production in any markets that will accept them.