Market Data

January 24, 2016

What’s Up (or Down) With China’s Economy?

Written by Sandy Williams

China’s economy, the second largest in the world behind the U.S., grew at 6.9 percent in 2015. That was pretty close to its target of 7 percent for the year but also the slowest rate since 1990. Data released by the Chinese government shows fourth quarter growth at 6.8 percent. As recently as 2007 China’s annual economic growth was in double digits, exceeding 14 percent.

The slowdown is not a surprise, it has been happening for awhile and most economists expect the slowdown to be a gradual loss of momentum rather than a dramatic drop.

According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, “In 2015, faced with complicated international environment and increasing downward pressure on the economy, the Central Party Committee and the State Council have maintained the strategic focus, comprehensively arranged both domestic and international tasks, adhered to the general work guideline of making progress while maintaining stability, actively adapted to and led the new normal, guided new practices with new theories, strived for new development with new strategies, innovated macro-regulation, deepened the structural reform and pushed forward mass entrepreneurship and innovation.”

“As a result, the economy has achieved moderate but stable and sound development.”

China’s high growth years fueled trade around the globe and the slowdown is now striking fear in the world market. Economists are wary of government figures, suggesting growth may be weaker than the official data appears.

One of the primary indicators for economic growth is industrial production which grew at a softer rate in December and for the full year. Industrial output rose 0.41 percent in December, after an increase of 0.58 percent the previous month. Full year 2015 industrial output was 6.1 percent, compared to 8.3 percent in 2014.

Retail, fixed-asset investment and construction activity continued to show gains but at a slower rate than previous months.

Currency Devaluation

Depreciation of the Renminbi (RMB) (also called yuan) set stock markets crashing. The surprise currency drop of 2 percent in August set off a panic in Chinese equities and world stock markets. That panic was repeated earlier this month when the RMB depreciated again.

There has been concern that China is deliberately devaluating its currency to boost exports. At the Davos conference Fang Xinghai, vice chair of the Chinese Securities Regulatory Commission refuted the idea.

“A depreciation is not in the interests of China’s rebalancing; a too deep currency fall would not be good for [domestic] consumption.”

The slowdown and currency depreciation has been met with overreaction by markets around the world, including the U.S. The Washington Post recently wrote:

“A surprise this year has been how much the perception of a slowdown in China has rocked U.S. financial markets. Only about 25 percent of the U.S. economy is tied to trade, which makes the country much less vulnerable than most other nations to a softening in China’s demand for imports. The fundamentals of the U.S. economy seem relatively strong, too, but that hasn’t prevented psychological contagion from infecting Wall Street.”

The Post quotes a top financial official at Davos as saying, “The issue is not whether the markets bounce up and down—of course they do, for China and everyone else—but whether Chinese officials are willing to let the numbers bounce.”

Doing so, said the official, would be in keeping with the free-market reform agenda and allow “the markets do the work of pruning excess industrial capacity and over borrowing among state-owned enterprises.”

Trade Is Down but Not As Much as Expected

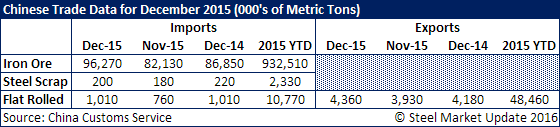

There is no question that the China’s weaker currency makes exports more attractive abroad—a boon to manufacturers looking for a deal, but a challenge to industries that compete with China’s exported goods. The steel industry, as we know, is one of the hardest hit, not only in the U.S. but in countries around the globe.

Import and export numbers fell in December but were stronger than forecast. Chinese exports were down 1.4 percent in December, improving from a 6.8 percent drop in November. The figure was well above the Reuters forecast of an 8 percent decline.

Sluggish domestic demand caused Imports to fall for the 14th consecutive month in December, down 7.6 percent, besting expectations of an 11.5 percent drop. The combined trade data produced a $60.09 trade surplus in December.

For the full year 2015 total trade fell 8 percent to $3.96 trillion according to China Customs data.

“The trade data support our view that, despite turmoil in Chinese financial markets, there has not been a major deterioration in its economy in recent months,” said Daniel Martin, senior Asia economist at Capital Economics.

Impact on Global Growth

The Chinese economy has nearly doubled in size in the past six years making it responsible for one third of global growth.

Partially in response to China’s slowdown, the International Monetary Fund lowered its 2015 global growth forecast to 3.1 percent. For 2016, IMF projects global growth at 3.4 percent and at 3.6 percent for 2017, a slightly downward revision of 0.2 percentage points for both years.

IMF economist Maurice Obstfeld said, “”When we forecasted China back a year ago,” he continued, “we were pessimistic relative to markets, and I think our forecasts have pretty much turned out to be right.”

IMF blames the reduced outlook primarily on challenges for emerging markets such as low oil prices and geopolitical tensions. The strong U.S. dollar also plays a part in the downgrade said Obstfeld.

China Reform

China has been on a path of economic reform since 1978 that is slowly moving towards rebalancing the economy by moving away from investment and manufacturing to consumption and services. The path has been a turbulent one with the 2008 financial crisis leading to run away government building and investment that supported GDP growth.

China is now pulling back on investment in the face of high debt and weak global demand for Chinese products. The government is encouraging the phase-out of low-end exports in favor of high-end manufacturing and the service industry.

Factory overcapacity continues to be a problem along with local government corruption that stymies central government policy directing cutbacks and shut downs of unprofitable or superfluous factories.

The service sector is beginning to emerge offsetting declines in manufacturing, expanding from 7.8 percent in 2014 to 8.3 percent in 2015. The goal is to achieve a sustainable growth rate driven by domestic consumption through services, innovation and entrepreneurship. China hopes to transform from a low to a high-income economy by 2020.

“In the short-term, the transition from investment to consumer spending is likely to be supported by fiscal resources. In the longer-term, household balance sheets look quite good and so we think there is significant scope for consumer spending to continue to grow,” says Andrew Tilton, chief Asia Pacific economist, Goldman Sachs Research

“The big picture we see for China is a bumpy deceleration growth over the next few years. But the bigger picture is we still want, and need, to see a rotation from credit intensive investment sectors to less credit intensive and, ultimately, more sustainable household consumption and services sector growth. That will involve a slower overall pace of economic growth but will ultimately be to China’s benefit.”