Market Data

March 31, 2017

US Gross Domestic Product - Q4 2016 Third Estimate

Written by Peter Wright

The headline report of GDP growth in Q4 came in at an upwardly revised 2.06 percent which was a decline from 3.53 percent in the third quarter. GDP is measured and reported in chained 2009 dollars and in the third estimate of Q4 was $16.813 trillion. GDP is defined as Consumption (C) plus Investment (I) plus Government Spending (G) plus [Exports (E) minus Imports (I)] or: GDP = C + I + G + (E-I)

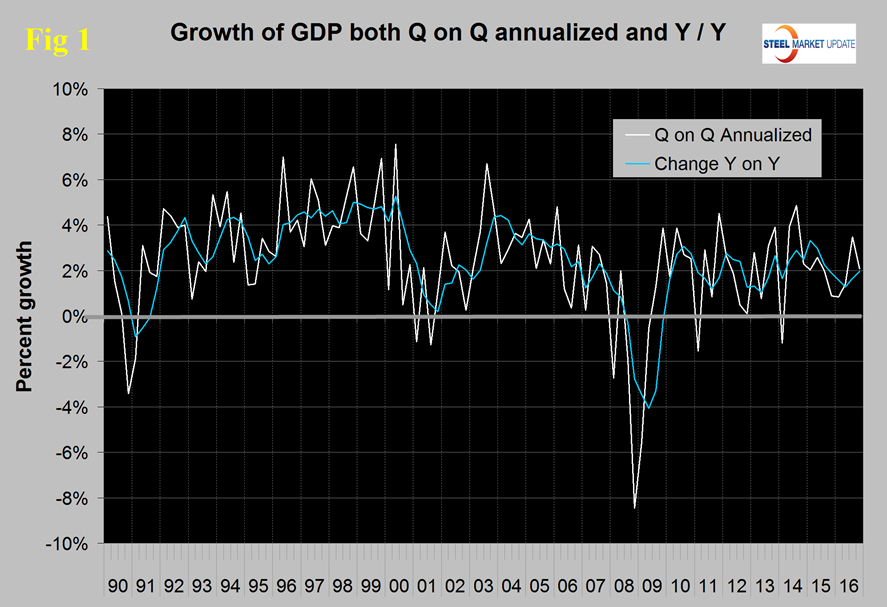

The growth calculation is misleading because it takes the Q over Q change and multiplies by 4 to get an annualized rate. This makes the high quarters higher and the low quarters lower. Figure 1 clearly shows this effect.

The blue line is the trailing 12 months growth and the white line is the headline quarterly result. Occasionally these numbers coincide which was the case in Q4. The long term average since Q1 2000 has been 2.09 percent. The average of the last eight quarters has been 2.11 percent therefore we conclude that in recent quarters the growth of US GDP is exactly in line with its average for the last sixteen years.

On February 3rd Gene Balas wrote, “In many instances, economic forces are simply beyond the control of politicians who desire to pass growth-friendly laws. Long-term growth of an economy is influenced by two basic factors: how many people are working (and how many hours they work), and how much they produce each hour. In other words, the long-run growth rate of an economy is simply growth of the labor force plus productivity gains.

In the short term, perhaps economic policies by governments can affect the growth rate of the economy, such as to make working more rewarding (thus drawing in more people to the labor force), or by affecting the incentives for companies to invest in productivity-enhancing technologies or equipment. What we see in the case with the election of the Trump administration is that markets do see a bump higher in short-term growth. Given that the labor force is expected to grow by 0.5 percent annually between now and 2024, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and that productivity gains are expected to be around 1 percent or so, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, perhaps this long-term growth rate is about what we can realistically expect.”

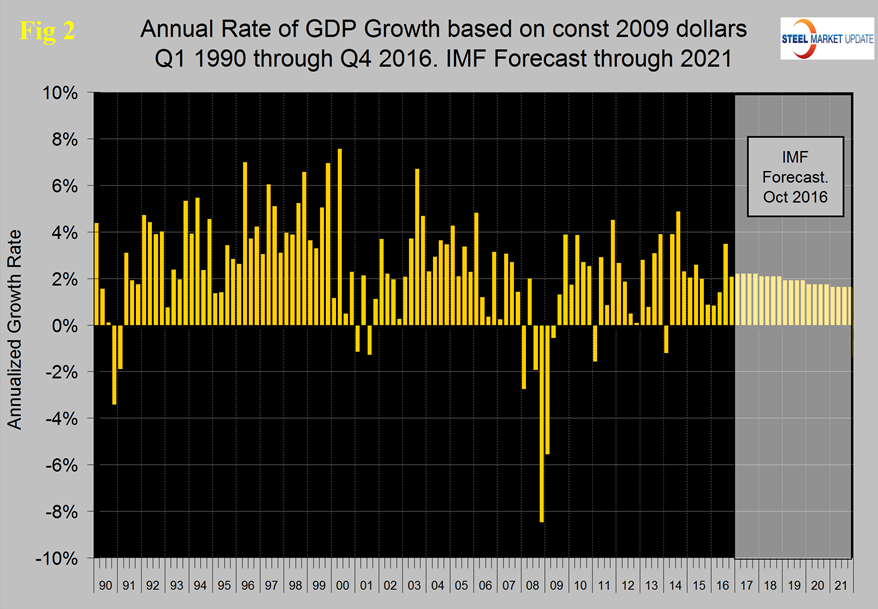

Figure 2 shows the headline quarterly results since 1990 and the October IMF forecast through 2021.

In their October revision, the IMF downgraded their forecast of US growth in 2016 from their April 2016 estimate of 2.4 percent to 1.58 percent and downgraded 2017 from 2.50 percent to 2.20 percent. We expect the IMF to raise their 2017 forecast in their next update which will be released in about two weeks from now.

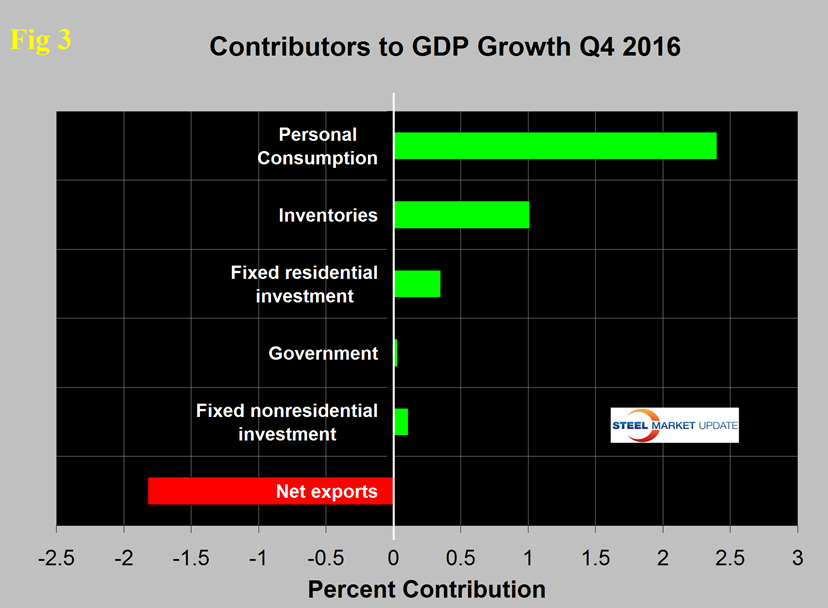

Figure 3 shows the change in the six major subcomponents of GDP in Q4 2016 and the dominance of personal consumption as a growth driver.

Exports were a major drag on growth in the fourth quarter and deducted 1.82 percent. This was the biggest difference between Q3 and Q4. Other changes were that the contribution of inventories increased from 0.5 to 1.01 percent, residential construction improved its contribution from negative 0.16 percent to positive 0.35 percent, the contribution of personal consumption improved from 2.03 percent to 2.40 percent. Personal consumption includes goods and services, the goods portion of which includes both durable and non-durables. Rising inventories have a positive effect on the overall GDP calculation and this was the case for the last two quarters following five straight quarters when inventories contracted. Over the long run inventory changes are a wash and simply move growth from one period to another. When a decline in one period is subtracted from growth, it can often be a healthy indicator for future periods. Such a decline suggests that there are lower levels of overall inventories which will set the stage for inventory increases – which will then add to GDP growth in the future. This seems to be what happened in the third and fourth quarters.

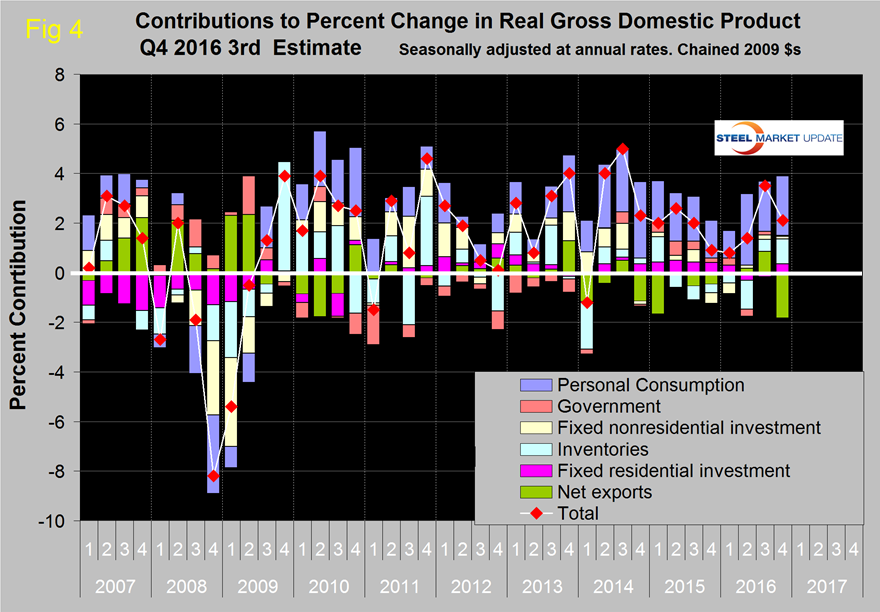

Figure 4 shows the contributors to GDP extended back through Q1 2007 and describes the quarterly change in the six major subcomponents.

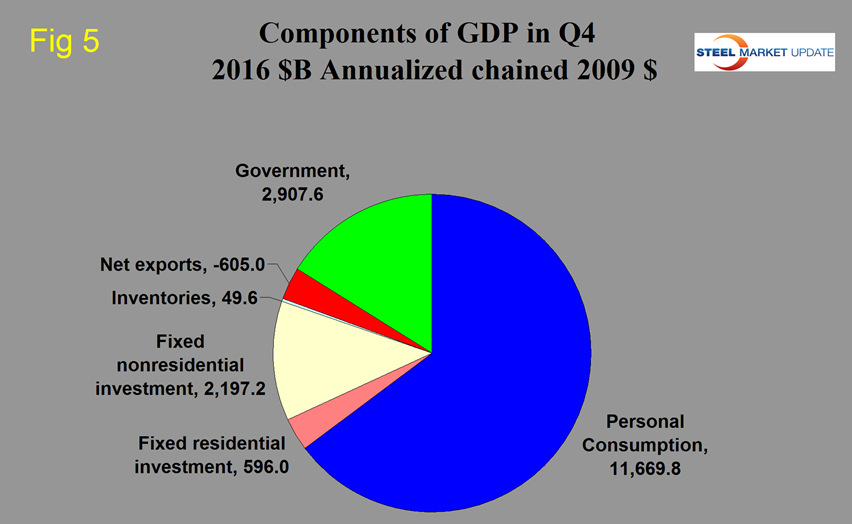

In Q4 the negative contribution of net exports was the largest since our data begins in Q1 2007. In Q2 the negative contribution of inventories was the greatest since Q1 2014 and in Q4 the positive contribution was the greatest since Q1 2015. Government expenditures made a small positive contribution in the last two quarters. Figure 5 shows the breakdown of the $16.8 trillion economy.

SMU Comment: The strong dollar resulted in a large negative contribution of net exports and that won’t change for the better anytime soon. The growth in personal consumption was the second highest of the last eight quarters which we expect to be a bright spot as consumer confidence translates into consumer spending. The growth of inventories made a large contribution to Q4 but as we reported above this is simply moving growth from one time period to another. Historically it has been necessary to have about a 2.5 percent growth in GDP to get any growth in steel demand so this latest estimate of GDP suggest that at least steel demand won’t contract in the immediate future. This relationship is a long term average and in reality steel is much more volatile than GDP. If GDP takes a dive then steel demand craters and if GDP takes a sudden upturn steel soars. Neither of these extremes is evident at present.