Overseas

April 14, 2019

CRU: Border Delays, Possible Business Model Changes in a No-Deal Brexit

Written by Tim Triplett

By CRU Principal Analyst Matthew Watkins.

In the event of a no-deal Brexit, the key short-term impacts on the European steel market are likely to be increased delays for material crossing the UK-EU border as well as modifications to the EU safeguard system. Beyond short-term behavior such as stockpiling, there are possible longer-term effects, perhaps primarily affecting the automotive supply chain.

The Odds of a No-Deal Brexit Have Risen

Although the ultimate form of Brexit remains unclear, the possibility has increased that the UK will leave the EU in the very near future without a deal setting out the terms of the future relationship between them. Under a no-deal Brexit, UK-EU trade would be on WTO rules—but as of day one no other conditions would exist to govern it.

UK-EU Steel Trade Could See Increased Costs Due to Delays

Toward the end of 2018 the UK government published the results of its economic modelling on several Brexit scenarios. These are instructive when considering what a no-deal Brexit might mean for the steel sector. In line with conclusions from that modelling, UK-EU steel trade could see additional costs incurred, arising in four possible areas:

Imposition of tariffs: In March, the UK announced it would impose zero import tariffs on almost 90 percent of the UK’s goods imports by value in the event of a no-deal Brexit. These would include all steel products as well as practically all steel-containing goods and would leave the status quo of UK-EU trade unchanged. Notably it does not include most finished cars, buses and motorcycles. Cars would largely have a 10 percent import tariff imposed.

The UK has also announced that it intends to replicate existing EU trade remedies on carbon steel products from non-EU origins. This would probably include the safeguard measures, which will be discussed further below.

In the future, if the UK were to decide to diverge from the EU’s external trade defense measures and erect lower antidumping barriers of its own, then logically the EU could in turn erect trade defense measures against the UK. These could be of a magnitude that equalizes for any arbitrage introduced. For example, current EU antidumping barriers against Chinese HDG coil have a lower boundary of 17.2 percent. If the UK lowered its own barrier to 10 percent, then would the EU seek to impose a 7.2 percent tariff on imports of HDG from the UK? Alternatively, perhaps the EU would impose a more targeted anti-circumvention barrier, preventing re-exports of Chinese HDG from the UK to the EU at tariffs less than the EU barriers, but not necessarily all flows of HDG between the UK and EU.

Imposition of new customs procedures: At least in the short term these would probably involve additional border checks and administrative procedures. Delays are widely expected at customs as a result of such checks across all goods flows and many expect to see large queues of trucks around ports.

“Technological solutions” are sought to resolve the question of how the Irish land border would be administered, and potentially in the future such solutions could reduce or remove these delays. It is not clear that such solutions exist today.

New regulatory burdens: These are presumed to be applicable as and when UK and EU standards diverge. On day one there will still be regulatory equivalence.

These burdens (= costs) might be quasi-fixed in the sense that businesses would need to do some one-off work to comply, but then may remain compliant until such time that standards diverge further.

Restrictions on temporary mobility for business purposes: This is unlikely to mean that truck drivers cannot accompany their cargoes across the UK-EU border, but may be applicable to secondments or similar arrangements. It is hard to see where this could make a material impact on the trading of steel, although perhaps it may incrementally reduce career opportunities able to be offered by multinational firms in the sector.

Modifications to the Safeguard System Likely

UK replication of existing EU trade remedy actions is understood to include setting up a safeguard system to mirror that which is currently in place around the EU28. Exactly how this might be achieved and how it might work is uncertain. CRU will shortly examine this topic in a separate Insight, but the working assumption is that the UK takes its share of the safeguard quotas with it, while the quotas for the EU27 will be correspondingly reduced.

As a net importer (see below) the UK may take a relatively large share of the EU28 quota volumes with it as it leaves. The net effect of this on EU buyers and mills is ambiguous and varies on a product by product basis.

Actions are Being Taken to Protect Against Delays

The major short-term impact is likely to be that product flows across the UK-EU border would be subject to delay. UK businesses and consumers of all kinds have been responding to this threat in recent months by stockpiling goods, including steel. Last summer, we looked at the possibility that such behavior might boost demand for packaging steel. Meanwhile on the EU side, we understand that some buyers are asking for, and achieving, discounted prices from some UK steel suppliers as an offset to the risk of logistics disruption.

Longer-Term Implications of Border Delays May be Limited

Although delays are sub-optimal, especially for just-in-time business models, are they actually likely to drive fundamental re-shaping of UK-EU trade flows? The answer will depend on what other options are available. EU steel consumers have the greater optionality here and could in theory substitute UK suppliers. Depending on location, these could offer more favorable logistics. UK steel consumers may seek a greater share of supply from domestic mills but face more of a limit on the availability of suitable product ranges.

In both cases we would note that opportunistic imported product, and/or that going to the stockholder sector, may be weighted towards purchases for inventory, in which case just-in-time is less likely to be a factor. For regular flows of imported product there will be underlying reasons for that arrangement such as product quality, supplier qualification or supply chain transparency. Such products will be far more difficult to substitute for, as the buyer will continue to require these conditions to be met.

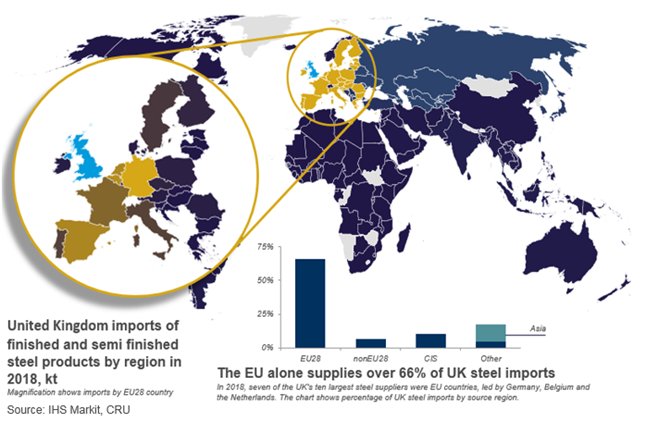

The UK is a net importer of finished steel products overall, and a net importer individually for all products other than tinplate, rails, wire rod and merchant bar. For these four products the options for UK buyers are broader and so any non-UK supply of these products may be more open to substitution by domestic mills. For products where the UK is a net importer, UK buyers are likely to remain dependent on EU supply, with or without delays. As the graphic illustrates, two-thirds of UK steel imports are sourced from the EU.

Automotive is a Key Risk Area

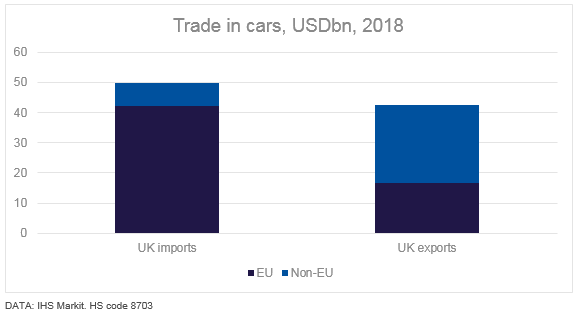

The automotive industry has featured prominently in discussions about trade post-Brexit for two reasons: input materials cross the UK-EU border multiple times during vehicle production, typically on a just-in-time basis; and finished vehicles manufactured in the UK are largely destined for the export market, of which the EU is a significant part. Meanwhile the UK is also a major market for EU-manufactured vehicles, especially from Germany.

Border delays would create real problems with this business model. Car manufacturers may not have the physical space available to store sufficient buffer stocks of input materials, and/or be unwilling to commit to the increase in working capital.

The UK and EU would both have 10 percent import tariffs against each other on cars. That may help UK vehicles displace some imports, though this would be subject to overcoming the cross-border supply chain problems above. However, it would undoubtedly harm the export potential for cars from both UK and EU suppliers.

As the chart above shows, this places a large amount of value at risk on both sides of the border. Given the current slowdown in the global auto sector, this additional downside risk arrives at a bad time.

Are There Any Offsets?

Which developments would have the potential to offset this risk? Exporters may stand to benefit from changes to the GBP/EUR exchange rate. Sterling weakened immediately after the 2016 referendum, and if the longer-term view is that UK economic growth will be constrained then this would suggest a medium-term weaker GBP. Other gains might be in corporate taxes, regulatory requirements and so on. UK exports could therefore potentially offset higher trade costs with the EU by reducing other costs. Another offset is the opportunity to trade more with non-EU nations. Extra-EU growth is predicted to be rapid in the coming years, affording UK exporters with new, expanding markets. However, given that queues at ports do not distinguish trucks from the EU and trucks from non-EU origins and that everyone will be stuck in the same queue regardless of where they are arriving from, this option is irrelevant in terms of offsetting expected border delays.

It may be possible that in the longer term the UK would seek to build domestic capability in its net import areas. We think it is not very likely that the UK government would prioritize and encourage a relatively low value-added, low-employment sector such as steel manufacturing in this way and if it did behave in this interventionist manner would rather focus on higher value-added sectors of the economy. That does not preclude individual steel companies seeking to fill the supply gap themselves, and it may be that the UK automotive supply chain would see an incentive to invest. Given the shift away from the internal combustion engine, perhaps those investments would be most attractive if weighted towards the electric vehicle supply chain.

Conclusion: Short-Term, Delays; Longer-Term, Possible Change in the Auto Sector

The most immediate impacts for steel of a no-deal Brexit would be delays crossing the border, as well as a probable re-design of the safeguard system. In the longer term, it seems unlikely that border delays would prompt structural changes in many areas of the steel sector. However, in the automotive supply chain this may not be the case. Here, delivery logistics are critical and currently incorporate a large degree of cross-border materials movement. There would also be import tariffs raised against finished vehicles that may incentivize change to existing business models.

Explore this topic further with CRU.