Market Data

April 24, 2020

CRU: “Houston, We’ve Got a Problem” – U.S. Oil Price Goes Negative

Written by Ross Cunningham

By CRU Principal Analyst Justin Hughes and Senior Cost Economist Ross Cunningham, from CRU’s Global Steel Trade Service

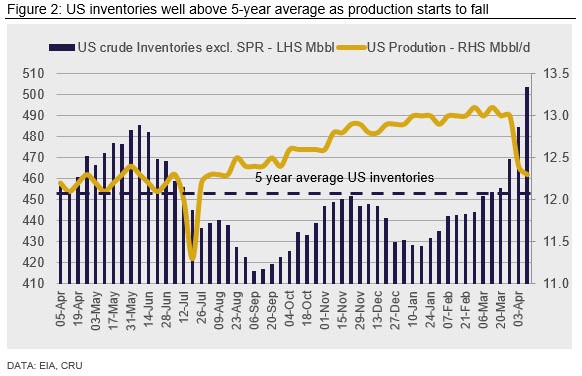

The international oil markets have been under severe pressure since the outbreak of Covid-19 with the rapid destruction of crude oil and oil product demand. Despite attempts for coordinated supply-side action by major oil producing nations, including those outside of OPEC, the pace of the unabated oil production throughout February and March, coupled with heavily discounted prices from Saudi Arabia and Russia, has meant dwindling global storage capacity will be completely full by mid-June. Current estimates indicate that the daily crude oil excess is nearly 30Mbpd. Storage at each refinery differs significantly and thus some regions are already unable to process or move additional liquid volume, and as such, are facing a crisis. From the demand side force-majeures are being issued as the implications of taking delivery of an oil product are considerable in the current marketplace.

Negative Prices Destroy ETF Longs

As such, on Monday, April 20, the last full trading day before the NYMEX WTI (Light Sweet [West Texas Intermediate] Crude Oil) May Future expires, the realities of this physical market situation were exposed for all to see. We have seen several heavy sour inland crudes trade at negative prices during April, but WTI was heavily offered from $20/bbl, to $1/bbl an hour before the close, before being hammered to -$37.63/bbl, the first negative close for WTI in the history of the contract.

Unlike Brent crude, which is settled in cash, WTI is settled physically. That means those that were long when the contract expired (April 21) for the May contract will have to take physical delivery of the crude. With Brent contracts settling in cash, traders will not find themselves in a situation where they are forced to sell at any price (even negative) to ensure they do not receive delivery of physical crude with nowhere to store it. This mechanism is the driver of WTI prices dropping below 0, and rightly grabbing the headlines. However, it becomes the representations of the deeper issue in the oil market today. One-third of global demand has been destroyed and a mere one-tenth of the global supply will be cut. This has combined to push global inventories towards capacity and the market reeling as a result.

Below is a brief overview of how we got to this point, what we should expect in the coming few months, and the feedback from the physical marketplace and the immediate actions being taken.

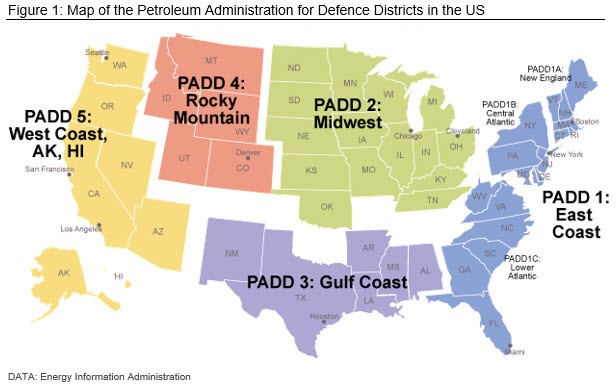

North American PADD and SPR Storage Near Full Capacity

Despite efforts over the years to increase storage capacity in the five Petroleum Administration for Defense Districts (PADDs – PADD 1 East Coast, PADD 2 Midwest, PADD 3 Gulf Coast, PADD 4 Rocky Mountain Region, PADD 5 West Coast), this has not been keeping up with the growth in domestic production. However, this has not been an issue until now, with utilization rates of storage capacity steadily growing from 60 percent to 80 percent or more over the past four years, but never reaching a critical level. Each PADD services both the local area and other crude slates from regions such as Canada. Extensive datasets are maintained by the EIA and break down capacity by product over time. It is of interest that the “shell volume” (total capacity of the storage) is differentiated from “working capacity” (approximately 80 percent of the total capacity). This is due to the top and bottom sections of the storage unit generally being considered unusable (or problematic to operate above), though this will certainly not be the case at this current time, thus shell limits are being reached. Crude moves in and out of the PADDs via pipeline primarily, but also some tanker and rail are utilized, most notably in PADD 4.

Cushing, Okla., is the delivery point for the WTI futures contract, and thus has a special designation, and reports separately to PADD 2 – Midwest, due to the importance and higher flux of crude moving through this region. The Cushing pipeline is a key piece of U.S. infrastructure with more than 24 pipes and over 7 Mb/day of capacity for inbound and outbound crude. Any holder of a WTI contract at expiry will need to take delivery of oil at Cushing. The scramble for capacity, pipeline availability or loco swap contracts on Monday, April 20, indicates the status of the physical terminals in Cushing, a status which has no likelihood or even capability to alter in the short to medium term. Pipeline managers are insisting on seeing full contracts of sale for crude using their systems to ensure owners of the crude legally have a venue for their oil to go, and to not clog up the network further.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DoE) is the largest single holder of crude oil, which it maintains for use in an emergency, such as a mass refinery outage, pipeline damage or military conflict that impacts crude availability. The U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserves (SPR) consists of four sites that have a cumulative capacity of 797 million barrels. The sites are in Freeport and Winnie in Texas, and Lake Charles Baton Rouge in Louisiana. The current understanding is that there is less than 150 million barrels of spare capacity. Also, the reserve stores sweet and sour crudes, so the capacity can only be filled with the appropriate grade. There are small reserves of oil products, though this is under the DoE umbrella and not the SPR.

Nationalized Oil Producers Drowning in Budget Deficits

While the current oil price collapse and impending capacity maximization is a truly international problem, it is seemingly being felt most severely in the U.S. due to the non-centralized oil industry. Without government intervention, the U.S. oil producers and energy sector are entirely exposed to market outcomes. The financial markets are currently focused on WTI, but when all global crude prices are assessed, the issues are widely spread.

OPEC nations have always required high oil prices to balance their budgets. Recent estimates before this crisis indicated that on the lower end were the likes of Kuwait and Qatar at $50/bbl, on the top side was Venezuela above $130/bbl, and with Saudi Arabia closer to $80/bbl (while having marginal cost below $10/bbl and the most profitable company in existence – Aramco).

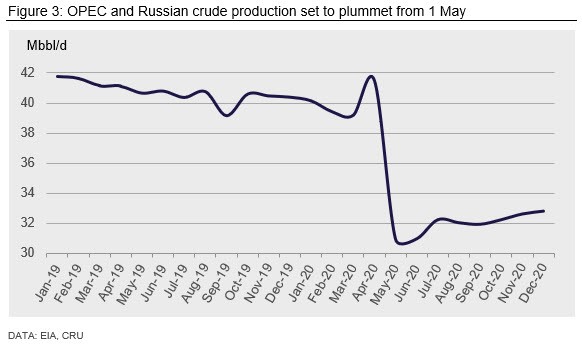

The meeting on April 9, 2020, between OPEC+ and several other key producing nations, most importantly, the U.S., was deemed a success when a 9.7Mbpd cut was agreed to be shared equally by OPEC+ (with the U.S. handling the Mexican cut – Mexico is a very well-known hedger of their oil production using financial derivatives, and thus cutting production made no sense). Quite how the U.S. would initiate cuts to production from a federal level to a private industry is yet to be seen. However, at best, this is one-third of the oversupply currently forecast to be amassing daily. In addition, the cuts were applied to the already inflated production levels of the “Saudi-Russia price war,” not the January OPEC+ meeting levels. In addition, the cuts were due to start on May 1, and thus we have seen some overproduction by Iraq, Kuwait, UAE and Saudi Arabia to capture as much income prior to this point, diminishing the impact of the total package. In general, the view is that the cuts will have to come organically anyhow by May, as storage was restricting buyers’ capabilities to take volume, as well as the complete loss of jet fuel, gasoline, diesel, bunker and MGO.

Unprecedented Oil Market Price Action Set to Continue

Estimates of the remaining total global capacity differ, but estimates are between 1.0-1.5 billion barrels, with maximum capacity reached by the end of May or June. In the past 10 weeks, more than 700 million barrels of crude have been put into storage, with more than 200 million in floating tankers. Owners of these vessels have either been extremely fortunate and have captured vast contangos to finance this material or, in the case of Vitol, have been shrewd traders who held ownership of pre-scrapped vessels in order to utilize them in situations of extreme price disparity.

Inland storage may not currently be at capacity, but booking for that storage facility is almost there, which essentially blocks off that volume and brings the immediacy of the physical market limitations to the fore. Chinese oil storage is now well over 1 billion barrels and reaching capacity in the coming months. India has reached critical capacity levels and refineries are now issuing force majeure on import contracts for crude (third largest importer of oil behind China and the U.S.). The Indian Oil Company (IOC) stated they have cut refinery runs by 25 percent, but with the national lockdown on top of already weak fuel demand, they require deferrals for at least one month from their major trading partners. Despite the investment over the past year and those contracts, which are also being put out to tender now for building of new capacity, the market is fighting a losing battle against the daily spare production.

U.S. Shale Industry Will be the Biggest Casualty

The U.S. shale industry is currently heavily indebted. At $20-$30 it was likely that many of the small shale oil producers would suffer as investors would move elsewhere for more reliable returns. That pressure is even greater now we have seen what limited storage capacity has done to prices. Presuming that demand for oil does not stage a miraculous recovery (and that likelihood during Q2 is almost zero), then the options left to the U.S. administration are to potentially offer monetary incentives to not produce crude. This is rather than buying the oil themselves and storing in the SPR, which is currently not an option. The issue with the halting of production is that many sites and wells would be lost and a restart would never be economical. Hence the hesitation in offering this solution and the lack of enthusiasm for it from the producers. When demand does eventually return, it will be slow, and storage will be at close to full capacity for many years to come. The oil industry may struggle to recover from this situation, and we suspect the U.S. will not be able to maintain their position as the top producer and continue to be a net energy exporter as they achieved in 2019. However, we are in an election year, and thus all options are no doubt on the table. The limiting factor will be that the U.S. oil industry are privateers, taking on nationalized petro-industries and governments running extreme budget deficits with oil sales as the only solution.

Volatility for Some Time to Come

It is important to note, the broader oil market is not in negative territories. The last day of trading front month May contracts fell well below zero as those with long positions were forced to sell to ensure they did receive physical delivery in Cushing where storage is very near capacity. At the time of this writing, the June futures contract for WTI was trading at $12/bbl while Brent is at $21.5/bbl. An exercise in futility is to assess the cumulative price across the next 18 months of the curve, which gives an average price of nearly $45/bbl.

At CRU we focus on Brent crude prices. It is the global benchmark, seaborne, and therefore can easily reach anywhere in the world that demands it and has fewer physical restrictions than the landlocked delivery point of WTI in Cushing. Brent’s front month is currently June and while prices have fallen 20 percent since WTI went negative it will likely stay in the $15-$25 range as we move through the trough in demand. However, given the demand outlook and the continued downward revisions to our economic forecast CRU sees further downside risk to the oil price. With inventories moving towards capacity, we could see the extreme price action of WTI on the front end to be repeated as June runs into expiry.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com