Market Data

October 4, 2020

CRU: Unit Labor Cost Improves Exchange Rate Forecasting

Written by Ross Cunningham

By CRU Senior Cost Economist Ross Cunningham and CRU Research Analyst Eric Lucking, from CRU’s Global Steel Trade Service

At CRU, we forecast the exchange rates for all the countries where our relevant commodities are produced. Our short and medium-term view is reviewed each quarter. This is anchored to our long-term forecast, which uses a methodology that considers the idiosyncrasies of the countries of interest. This article sets out our rationale and works through some examples to highlight the importance of wage growth, productivity and consumer inflation as drivers for long-term foreign exchange rates.

Exchange Rates are Vital for Comparing Costs

Exchange rates are arguably the most important driver of cross-country costs, determining the competitiveness of one production site over another. They influence both production costs and trade flows and often underly the competitive dynamic between imported and domestically produced products. Recently, with the impact of Covid-19, we have seen large depreciations in various currencies versus the U.S. dollar (USD). This has had an impact on the cost competitiveness of assets in different countries.

A depreciation against the U.S. dollar is sometimes portrayed in the news as a national failure, but this depends on what end of the trade balance you sit in. In its simplest form, if your business is a net exporter of a product sold in USD, then a depreciation of your local currency against the USD is beneficial to you as your exported product (traded in U.S. dollars) is cheaper than your competitors’ who have not depreciated. Conversely, if you are a net importer, then you will lose out from a depreciation of your local currency.

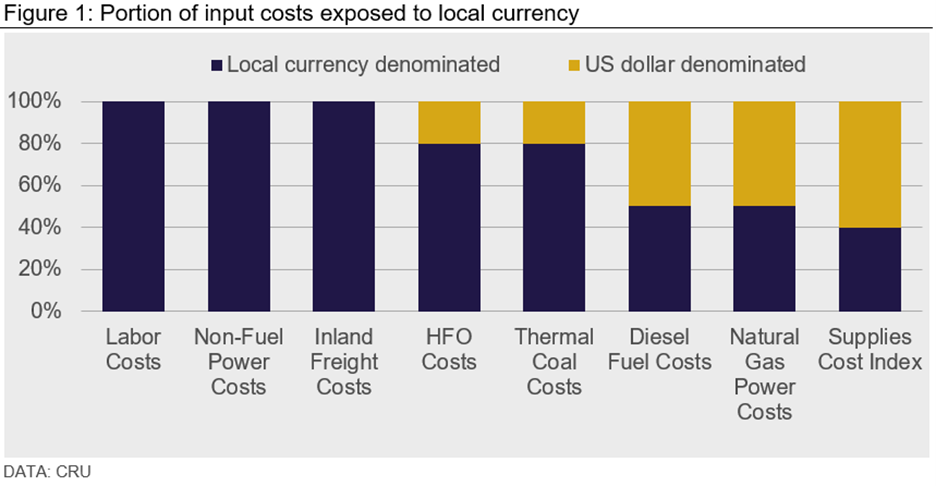

In commodities, there are more complexities to consider, however. Each mine, smelter or mill will have different process flows that require varying amount of inputs—differing amounts of fuel, capital equipment, power, labor costs and consumables costs. These costs have a different amount of exposure to foreign exchange rates. For example, we estimate that on average, labor costs are nearly always fully linked to local currencies, while heavy fuel oil (HFO) and thermal coal costs have ~80 percent of their costs associated with local currency and consumables only around 40 percent. The more your costs are linked to local currencies, the more you benefit in international markets from a depreciation against the dollar.

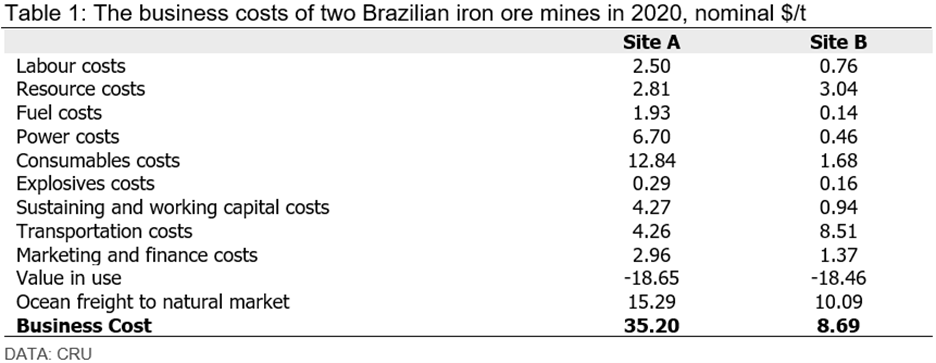

The importance of these differences is highlighted effectively when we compare the two iron ore mines in Brazil. Site A has a higher business cost at $35/t compared to Site B at $9/t in 2020. This is because product at Site A needs more beneficiation and therefore has comparatively higher labor, purchased power costs and consumables costs. These costs have much larger proportions in local currency than in U.S. dollar terms, which means that a depreciation in the Brazilian real would benefit the Site A mine more than the Site B in terms of lower USD business costs.

Understanding exchange rate movements is important to producers, consumers and investors. The movement of foreign exchange rates is fast and incredibly volatile and therefore it could be deemed unnecessary to look further ahead than the short-term. This is not strictly true. For example, the life span of a copper mine from exploration, planning, financing through to the depletion of the reserves can be upwards of 30 years, therefore having an idea of how exchange rates will move in the long term is very important to corporate strategists, site planners and investors alike. The pre-tax net present value of cashflows for the Escondida concentrate operation in Chile in 2019 was estimated to be ~USD25 bn using a 10 percent discount rate. A 10 percent permanent depreciation of the Chilean peso from 2020 onwards (and holding copper prices constant) increases the pre-tax net present value by 11.7 percent, raising it to ~USD28 bn.

Inflation Differential is Not the Only Exchange Rates Predictor

According to the relative purchasing power parity theory (PPP), if the inflation of the analyzed country grows faster than the inflation in the benchmark country, the nominal exchange rate will be pressured to depreciate, and vice versa. Can inflation, on its own, be used to forecast exchange rates?

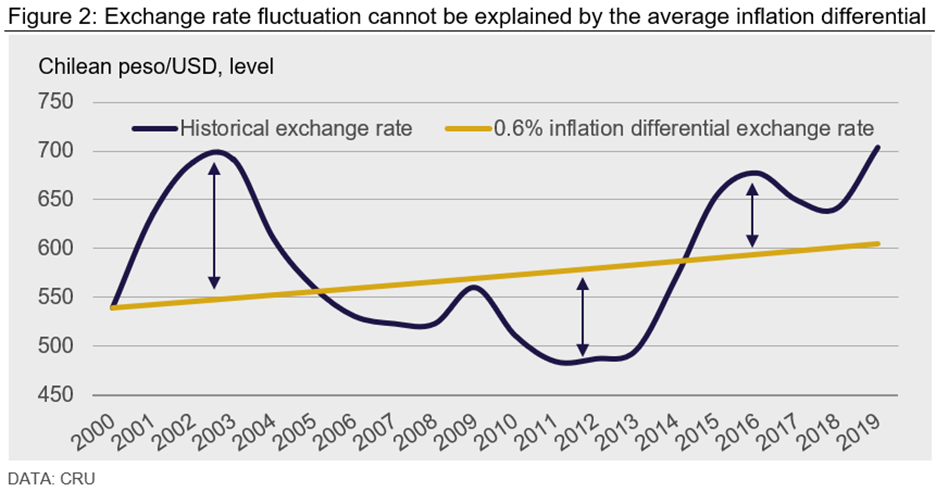

Not necessarily. Let us take Chile and the USA as an example. The Banco Central de Chile targets a 3 percent CPI target against the average 2.4 percent (2 percent PCE) inflation objective of the Fed. According to relative PPP, the comparatively higher inflation rate in Chile should be offset by a depreciation of the Chilean peso against the USD and so the peso should depreciate by 0.6 percent each year. However, when we look at the actual historical exchange rate of Chile, there are large and persistent deviations from this simple relative purchasing power parity theory rule.

In countries with free-floating exchange rates and inflation targets such as Chile, central banks will let supply shocks affect price levels and competitiveness and so exchange rate levels will fluctuate. Thus, average inflation target differentials alone are not sufficient to forecast exchange rates, and more variables need to be tracked.

Another weakness of relative purchasing power parity is that it cannot be used to forecast exchange rates for the many important countries without a clear inflation target or stable inflation, like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Argentina, Iran, or India.

Unit Labor Cost Helps Capture Past and Future Trends

At CRU, we have amended our long-term forecast methodology to consider unit labor cost competitiveness. Inflation differentials are still accounted for, but two other variables are added: labor productivity and real wages. Our productivity driver, defined as the growth rate in GDP per worker, comes from our Long Run Macro. This is forecast to 2050, and considers specific features of developing countries, such as India, China and SE Asia. Unit labor cost, obtained by dividing real wages by productivity, is a key driver of the international competitiveness of a country. When the unit labor cost in the analyzed country increases above its competitors, its exchange rate is pressured towards depreciation, to keep its products in the international market competitive. This measure becomes very useful when analyzing countries where an increase in productivity is not followed by a rise in wages that is strong enough to offset the impact on costs, leading to an increase in competitiveness.

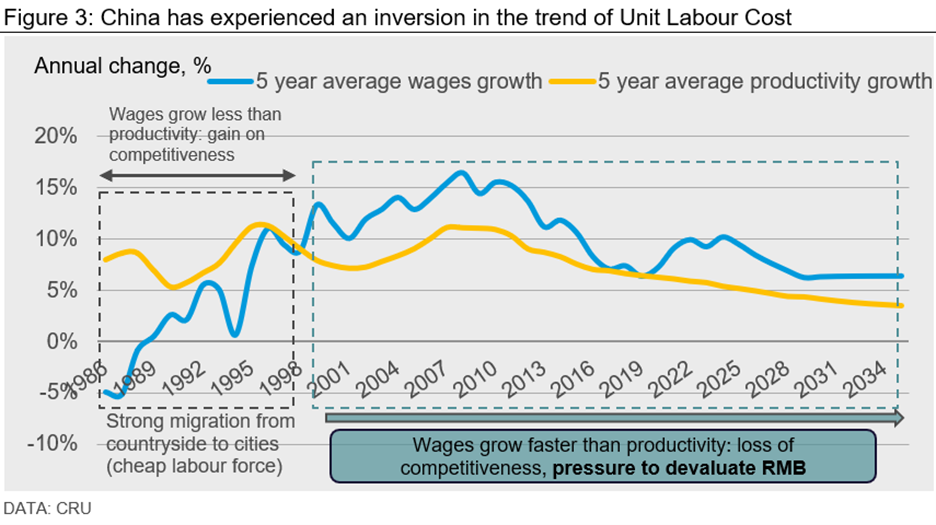

A very good example is China’s export-led strategy. In the 1990s, productivity growth in China was rapid, but real wage growth did not keep pace. The main reason was the sudden possibility that the many skilled workers living in rural areas could migrate to urban areas. The hukou policy, an internal passport system used by the Chinese government, regulated this flux of rural-to-urban and urban-to-urban migrants. Productivity improvements in agriculture lowered urban food costs. The vast availability of cheap but productive workers kept average wages low, meaning that unit labor cost was decreasing. Over time migration slowed down, as the reserve of young skilled labor was exhausted. At the same time, the demand for skilled labor increased, and migrants’ living conditions, expectations and thus wages started improving. Around 2000, we saw a reversal in the competitiveness trend, with wages growing faster than productivity and unit labor cost increasing. To counterbalance the loss in competitiveness, the renminbi (RMB) exchange rate was pressured to depreciate; this started happening from 2013.

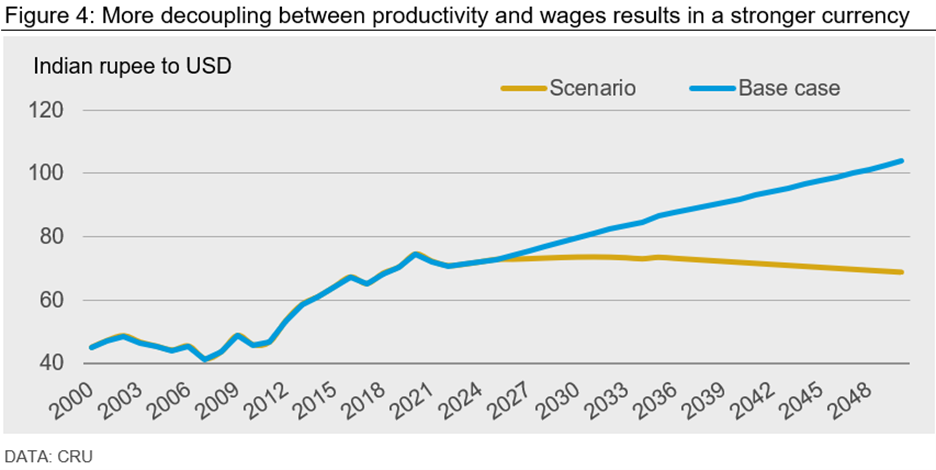

Unit Labor Cost is a better measure of international competitiveness than just CPI inflation and, by running scenarios, we can capture possible future trends that are an outcome of the interrelationship between producer prices, productivity and wages. Taking India as an example, we currently forecast a significant depreciation as unit labor cost is high as well as inflation. India has a massive rural population share of over 65 percent. With a sufficiently strong and effective push from the government towards urbanization, the country could experience strong rural-to-urban migration flows that would keep real wages low, in a similar fashion to China. In a scenario where we account for this, we no longer forecast a significant depreciation, but instead a slight appreciation.

Exchange Rate Forecasting Requires Accounting for National Idiosyncrasies

We have shown that using only average historical inflation differentials to forecast long-run exchange rate trends is not a good enough rule. A more comprehensive picture of persistent trends emerges from understanding the drivers of competitiveness, namely the Unit Labor Cost (ULC). This is calculated using the differential between wages and productivity and is especially important for countries with more heterogeneous monetary policy regimes and different policy objectives. Prominent examples would be China with its managed float regime, the Democratic Republic of Congo with its unstable inflation, Chile with its high sensitivity to copper prices, and Argentina with its systematic balance sheet difficulties.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com