AMU

June 6, 2025

AMU: Bumper-to-bumper breakdown of aluminum’s changing role in vehicles

Written by Nicholas Bell

The aluminum industry’s relationship with the automotive sector is as complicated as ever. At Aluminum Market Update’s P.A.T.H. forum in Chicago last week, Ducker Carlisle’s Abey Abraham offered a look at current market dynamics.

Editor’s note: This article appeared first in Aluminum Market Update, an SMU sister publication devoted to the aluminum and nonferrous scrap markets. You can find the latest content on AMU’s website. And you can register or take out a free trial here.

Sticker shock and softer forecasts

Abraham set the stage with a sobering figure: The 2025 North American vehicle production forecast has been cut to just 14.1 million units, down sharply from the pre-Covid expectation of 17.7 million. That’s a stark disparity from the 16 million-unit baseline for a “healthy” automotive environment, he said.

Sticker shock is partly to blame. Tariffs on imported vehicles and auto parts, inflation, and financing costs have converged to push the average new vehicle price above $48,000, with electric vehicles well over $60,000, stretching consumer tolerance.

Steel is hanging on

One of the more pointed insights from Abraham concerned the strategic reversion from aluminum back to steel in hang-on parts, which is sector parlance for parts like non-load-bearing exterior panels attached to a vehicle’s body, such as hoods, doors, and fenders.

These components account for a large share of aluminum sheet use in vehicles and are being swapped for steel alternatives, not for performance reasons but for cost control.

Critically, because hang-on parts aren’t structural, automakers can make that change without triggering a full vehicle CO2 recertification. So, despite steel having a higher carbon footprint, the transition has happened because it allows for immediate per-unit savings without regulatory penalty.

To salvage or to scrap

Abraham also highlighted a lesser-known shift whereby OEMs and insurers are opting to remove high-value hang-on parts rather than sending them to recyclers. Instead of treating an entire unit as an end-of-life vehicle, automakers and auto parts manufacturers are salvaging high-value, hang-on parts akin to the aftermarket sector. There has been a shift toward greater adoption of these tactics upstream to capture residual value, and to mitigate the impact of replacement cost inflation.

As he put it, companies like LKQ and Phoenix Parts are building business models around identifying which parts are worth removing and reselling before a car hits the shredder. That means fewer complete vehicles are making it to recyclers with all their aluminum intact and introducing a new class of scrap buyer into the mix, blurring once-clear lines between aftermarket resellers or maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) operations and traditional shredders.

Selective substitution and greater reuse of repair parts, coupled with the production figures mentioned at the top of the discussion, raises questions about scrap availability and generation rates from the end sector moving forward. The recovery rate has become harder to predict as OEMs try to tighten their grip on scrap streams.

Biggers castings blurring lines

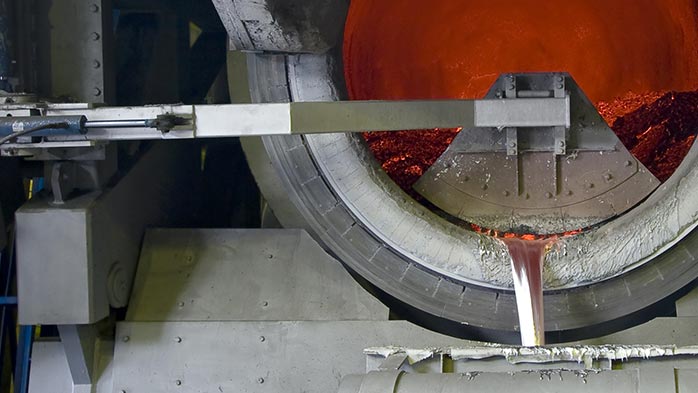

Ironically, the brightest development in automotive aluminum is also contributing to the opacity of scrap’s outlook: giga-casting. These massive structural castings, pioneered by Tesla and increasingly adopted by others, consolidate dozens of components into a single high-pressure, die-cast part. They cut cost, save time, and increase a vehicle’s lightweighting properties and vehicle stiffness, they’re also making scrap chemistry and recovery murkier.

While increased adoption is using more secondary aluminum overall, in line with the industry’s demand aspirations, many of these castings are beginning to approach primary-grade purity, despite the reliance on secondary aluminum alloys. And their sheer size and complexity raise end-of-life challenges: They’re harder to dismantle and tougher to sort.

Still, Abraham offered a counterpoint: Not every auto manufacturer can leap into giga-casting. The capital required to install and justify a giga-press is immense. A typical automaker needs multiple vehicle lines and high throughput to justify the cost and recapture their initial investment.

In conclusion

Despite the production headwinds and selective substitution, Ducker’s forecast still sees aluminum content per vehicle growing to about 556 pounds of aluminum per vehicle by 2030 using a weighted average of vehicle types, up from an estimate of about 505 pounds for the current year.

Since engineering decisions are planned out five to six years ahead of production, limiting their flexibility to substitute materials for components that aren’t “hang-on” parts, their forecast remains largely unchanged.

While the session painted a picture of an end sector in recalibration mode, the message was clear that aluminum isn’t losing relevance. But it’s growth is no longer linear when it comes to content utilization and the scrap it generates.

The narrative moving forward places a greater emphasis on how and where value is being captured or left behind.