Market Data

March 9, 2014

The Ukraine Crisis from a Steel Perspective

Written by Sandy Williams

An ousted president, deadly violence, military insurgence and a possible secession—the crisis in the Ukraine has been moving at an alarming speed in the last several weeks.

As the Ukraine struggles to create a new government, economic sanctions are increasingly being considered by the global powers to sway preferred outcomes. The US and the EU are imposing sanctions against Russia for its interference in Ukraine domestic matters. The US has restricted travel visas for Russian individuals deemed a threat to Ukraine sovereignty. The EU has suspended talks with Russia on visas and an economic pact. Russia warned the Ukraine it will increase natural gas prices should the country side with the EU. Within the Ukraine, sides are forming as pro-Russia supporters in the Crimea parliament refuse to recognize the interim government in Kiev and propose seceding from the Ukraine.

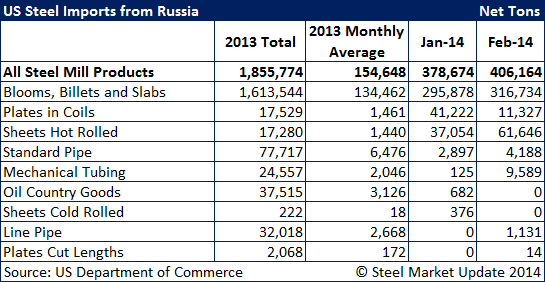

So far economic sanctions by the US and EU are still in the deliberating stage. SMU asked David Phelps, contributing writer and past president of AIIS, what would happen if the US put sanctions on imports of Russian steel.

This is a really technical legal question, fraught with presidential policy as well as legal,” said Phelps. “The Treasury Department’s Foreign Asset Control is where it would end up for operational control. The DOT office is in charge of enforcing trade bans against Cuba, N. Korea, that sort of thing, and so once the political decision is made as to how far to take the sanctions — which at this point are only talk as far as I know — the enforcement I assume would go to Treasury.”

“Of course in the wonderful world of government, DOC would be involved, but I have no earthly idea how. For example, the suspension agreements with Russia would be affected by Obama sanctions — and I also wonder if he would have to get Congressional approval too. It is one thing to limit asset movements — and really complicated since we have Russian assets on the ground here and they have American assets on the ground there — it is another thing to reach into the anti-dumping law and alter something. I just don’t know how that would work, or even if, short of a declaration of war or total freeze of trade, it would be done.”

In the Ukraine, ramifications for the steel producers may be seen once the crisis is resolved and it is known which way the country will lean—toward trade agreements with the EU or alignment with Russia. The outcome could affect both the Ukraine steel industry and global steel exports.

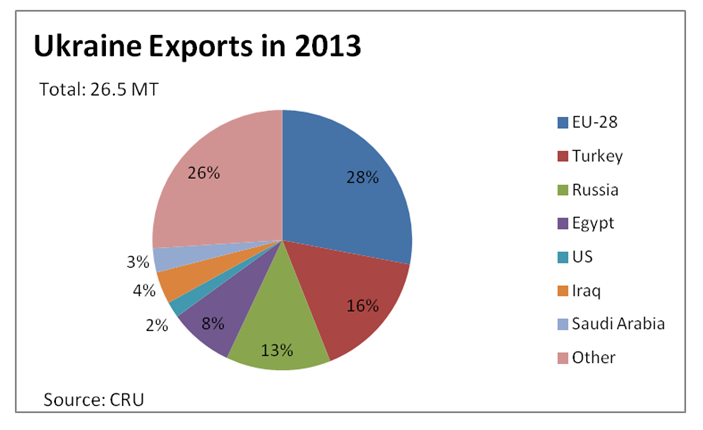

The Ukraine exports about 75 percent of its steel production with 13 percent going to Russia, 28 percent to the EU, 16 percent to Turkey and the rest to a variety of countries (including 2 percent to the US). It was the seventh largest exporter of iron and steel products in 2013 and is the largest global exporter of steel billet, according to a recent report by Dimitry Popov, research analyst for CRU Insight which examined the potential effect of the crisis on the Ukrainian and global steel industry. According to Popov, 35 percent of Ukrainian rebar was sold to Russia and Turkey in 2013 and Ukraine is the fourth largest exporter of steel slab.

The new government has said it would embrace the EU trade negotiations that were aborted under ousted president Viktor Yanukovych. Russia has warned it will impose trade tariffs on imports from the Ukraine if an EU trade agreement is signed. Tariffs may force Ukraine steel producers to shift their market focus from Russia to the EU and beyond to find buyers for its products. The depreciating Russian ruble has also made steel sales to Russia unattractive, especially for Ukrainian rebar producers who are already turning to new overseas markets, said Popov. This influx of rebar to the market has resulted in increased export price competition, “particularly impacting rebar prices which have fallen to a three and a half year low on an FOB Black Sea Basis.”

CRU forecasted a 3.4 percent increase in finished steel demand in the Ukraine for 2014, but said the political turmoil will likely result in lower domestic demand and a downward revision to its forecast.

The Ukraine also imports coking coal from Russia to supplement its domestic supply which is an inferior product for pulverized coal injection. The Ukraine’s weakened currency and potential trade barriers with Russia could result in higher coal prices for the Ukraine. At the same time, the weaker currency will make Ukrainian exports cheaper, a plus for the Ukraine if it needs to divert steel products to the EU instead of Russia.

Natural gas pricing is also threatened and has been at the crux of this crisis. Part of why Russia is so interested in the outcome of the Ukraine political upheaval is due to the pipelines crossing the Ukraine from Russia. Yanukovych’s administration arranged a discount of Russian natural gas at the beginning of 2014 that lowered gas costs for Ukrainian steel producers by 9.5 percent—a discount that could be rescinded at the end of the quarter. Natural gas is used along with PCI coal in blast furnace injection. “If natural gas prices were to rise again, especially while the hyrvania remains weak, the cost to steel mills will increase significantly,” said Popov.

The CRU Insight also suggests that further deterioration of the political situation in the Ukraine may threaten steel mill operations as well as scare off potential international steel buyers.

Crisis Timeline

For those of you who need to catch up, the crisis has moved at a break neck pace since it began in November with a decision by President Viktor Yanukovych to abandon an agreement with the EU that would strengthen ties and trade opportunities and instead accept a $15 billion “bailout” from Russian President Vladimir Putin. Over 300,000 protesters converged on Kiev in December taking over the city hall.

In January the protests turned violent in clashes between police and demonstrators and results in the resignation of Yanukovych. February violence leaves dozens dead and hundreds injured. February 22 Yanukovych flees the country and is charged with the deaths of more than 80 protesters.

In late February, Putin orders military exercises in Western Russia and armed men in Russian uniforms take over airports in Crimea. Russian marines are sent to guard a coast guard base in Sevastopol in the Ukraine. Sevastopol is also base for the Russian Black Sea Fleet that that was allowed to remain in the Ukraine under a 2010 agreement that gave the Ukraine a 30 percent discount on natural gas from Russia in return for use of the base until 2042. President Obama warns Putin “there will be costs” for military intervention in the Ukraine. The US announces the addition of six US F-15 fighter jets to the NATO forces in the Baltics.

Secretary of State John Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov meet in March to find a diplomatic settlement for the crisis but no agreement is reached. President Obama seeks visa and economic sanctions on Russians who “support destabilizing the Ukraine.” The EU freezes assets of Yanukovych and other senior Ukrainian officials for charges of corruption and considers sanctions against Russia.

Putin discusses his view on the Ukraine crisis with journalists on March 4. Defending the use of military, Putin said, “The only thing we had to do, and we did it, was to enhance the defense of our military facilities because they were constantly receiving threats and we were aware of the armed nationalists moving in.” Putin also said a military presence was necessary to defend ethnic Russians in Crimea.

Putin does not acknowledge the legitimacy of the interim government in the Ukraine but said, “There is something I would like to stress, however. Obviously, what I am going to say now is not within my authority and we do not intend to interfere. However, we firmly believe that all citizens of Ukraine, I repeat, wherever they live, should be given the same equal right to participate in the life of their country and in determining its future.”

The US is obligated to support the Ukraine independence because of an agreement signed in 1994 called the Budapest Memorandum in which the US, Russia and the UK committed to uphold the territorial integrity of the Ukraine in return in for nuclear disarmament in the Ukraine.

Kiev says the political and military interference by Russia is threatening its borders. The first article of the memorandum reads: “The United States of America, the Russian Federation, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, reaffirm their commitment to Ukraine … to respect the Independence and Sovereignty and the existing borders of Ukraine.”

Kerry told journalists following a meeting with Lavrov on March 5, “We will not allow the integrity, the sovereignty, of Ukraine to be violated – or for that violation to go unchallenged. Russia made a choice. We have clearly stated it is the wrong choice to move troops into the Crimea. Ukrainian territorial integrity must be restored and maintained.”

In the latest turn of events in the Ukrainian crisis, on March 6 Crimea parliament members offered a referendum to voters on whether Crimea should remain in the Ukraine or join with Russia. The vote is scheduled for March 16. The proposal was denounced by Ukrainian Interim Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk and world leaders as an illegal decision.

“Crimea was, is and will be an integral part of Ukraine,” said Yatsenyuk.