Prices

October 31, 2019

CRU: Tariffs and Populism Will Continue to Drag on Global Growth

Written by Jumana Saleheen

By CRU Chief Economist Jumana Saleheen

We expect world GDP to grow by 2.5 percent this year and next; in other words, we expect global growth to be broadly stable at current rates. The story for world industrial production, instead, is one of a mild recovery from 1.4 percent in 2019 to 2.2 percent in 2020.

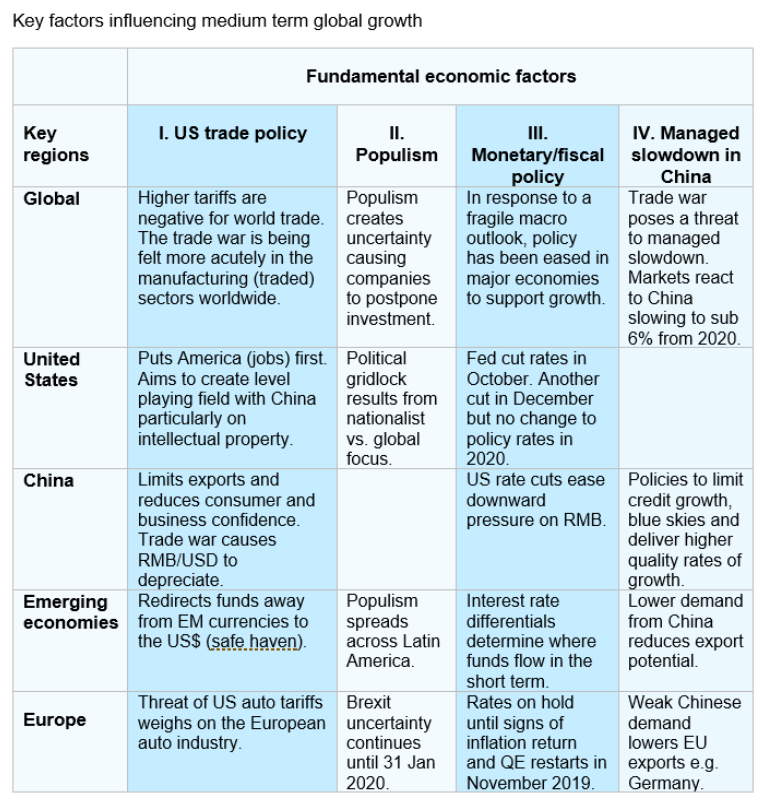

Our view is that four key economic factors will shape our forecast over the next five years:

U.S. trade policy, the continuation of populism, monetary and fiscal policy easing and the managed slowdown in China. Here we set out our latest views on these topics.

The Trade War is Likely to Continue Well Beyond 2020

The U.S. trade war against the rest of the world has taken two distinct forms:

* U.S. tariffs levied on all economies to protect U.S. industry on grounds of national security—Section 232 investigations unless the country has received exemption

* U.S. tariffs on China—Section 301 investigations

Section 232: The Threat of Auto Tariffs Loom in November 2019

President Trump’s promise to bring manufacturing jobs back to the U.S. is the driving force behind the Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum as well as the soon-to-be concluded investigation on automobiles and automotive tariffs. The report on the automotive sector investigation by the Commerce Department was submitted to the President on Feb. 17, but was not made public. However, on May 17, the president announced that imports of automobiles and certain automotive parts threaten U.S. national security because these impede the global competitiveness and R&D capabilities of American-owned vehicle producers, which are needed for U.S. military superiority.

In addition, the president directed U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer to negotiate with the European Union and Japan (which account for around 47 percent of U.S. auto imports) to open their markets further to U.S. exports in return for no tariffs on U.S. imports of their cars and parts. Japan and the U.S. signed a trade agreement on Sept. 25, to come into effect at a future unspecified date, which resulted in the deferral of additional negotiations on automotive issues. There has been no resolution with the EU to date.

President Trump is due to decide whether new tariffs on autos and parts will be imposed on the EU, and potentially other countries, by Nov. 13. Our view is that there is a high chance that some tariffs will be imposed on the EU in the next six months.

Section 301: A Comprehensive U.S.-China Trade Deal is Unlikely in 2020

U.S. protectionism towards China rose in 2018 and escalated in 2019. China and the U.S. have agreed to a “mini deal” or phase I deal this month, where the planned increases in tariffs on Oct. 15 were halted. That said, both parties are yet to sign on the dotted line. The next meeting between Trump and Xi was due at the Chile APEC Summit on Nov. 16-17, but that meeting has now been cancelled due to the political unrest in Chile. We expect further details to be announced in coming weeks and are optimistic that the phase I deal will be signed before Christmas. But our base case view is that a comprehensive trade deal, that takes U.S.-China trade war uncertainty off the table, will not be reached in 2020.

Trade War Against China: How Much Longer Will It Continue?

Our view is that the trade war is likely to continue beyond 2020, potentially even outlasting Trump. Trade war uncertainty will continue to weigh on global growth and spur the reorganization of global production chains. This view rests on three arguments:

* The trade war is not just about Trump.

* The EU shares the U.S. view on China’s trade practice.

* The trade war is not just about trade.

Will the tariffs on China be removed if Trump is not re-elected in 2020? We do not think so. That is because Trump represents the broader anti-China feeling that now exists in U.S. society and politics. A recent poll by Politico showed that 60 percent of the U.S. public have unfavorable views on China. Some of this comes from parts of the economy that have not benefited from the growing trade with China, and globalization more broadly. Indeed, a consensus has emerged that while free trade increases world GDP, the benefits of trade are not felt equally. Trade shifts production across countries and creates winners and losers. The IMF has noted that U.S. manufacturing workers have lost out to rising international trade over the past two decades. Unfavorable views on China have also grown from the accusation that China has broken WTO rules and needs to be held accountable for it.

EU trade commissioner Cecilia Malmström said, “With regard to China, we see many things in the same way as the U.S. does. We are defending ourselves against state-subsidized companies buying up our most creative companies, we are fighting against intellectual property theft and for greater transparency.” Importantly, the EU disagrees with the U.S. approach to deal with these issues. It does not believe in tariffs, as they hurt growth, nor does it agree with unpredictable trade policies. From China’s perspective it is making progress on intellectual property protection through the passing of stronger domestic laws.

The conflict between the U.S. and China is about trade fairness, but it also is a battle over technology and the race to secure first place as the most powerful economy in the long run. In recent years, China has been challenging the U.S. both economically and militarily. The U.S. now has little incentive to guide the global economic system, enabling the emergence of a strategic rival.

Will the Average Level of Tariffs Rise Further?

In “U.S.-China trade war will rumble on even if there is a ‘mini’ deal,” our CRU China and CRU USA offices surveyed local business in the metals and mining industry and found that, while the majority believe the trade war is hurting U.S. and China growth, neither want their country to compromise and resolve the trade war or reverse tariffs. This and other sources (e.g. local media reports) point to a hardening of the bilateral relationship between the two economies. While it is a very difficult call to make, on balance we judge that the average rate of tariffs is more likely to rise further than to fall over the next five years.

Populism and Political Uncertainty Drag Down Growth

The past few years have seen a wave of rising populism and nationalism in Europe and the Americas. We use the term populism to describe a political rhetoric which aims at representing a share of the population who feels overlooked by ruling political parties usually seen as an established elite. It is often unclear how these forces feed through to affect the real economy, but we separate its impact into two broad two channels:

* If the group that feels overlooked is large enough to gain a majority in government, it can push through policies that benefit its members. These policies could be protectionist in nature. For example, in the U.S., populism has given rise to protectionist or other growth-reducing policies that are not beneficial to long-term growth.

* If the group that feels overlooked is just shy of a majority in government, it can produce political gridlock and policy paralysis or uncertainty that tends to weigh on growth as businesses and consumers try to figure out where the economy is headed. For example, in the UK, the country is split on the Brexit decision. This led to political gridlock and the inability to deliver the UK’s departure from the EU by March 31. Our forecast still assumes a soft and orderly Brexit outcome. The latest development is that Brexit has been delayed until Jan. 31, 2020, with an election planned for Dec. 12.

Monetary and Fiscal Policy Stimulus is More Limited

In the U.S., on Oct. 30, the Fed cut rates for a third time in 2019. Our base case expects one more rate cut in December with the Fed on hold after that. This means that the four interest rate increases in 2018 will have been fully rolled back by the end of 2019. In the Eurozone, the ECB cut the deposit facility rate by 10bp in September and will restart QE next month through purchasing EUR 20 billion in bonds.

The IMF October world economic update and the ECB September press statement warned that major central banks have less policy firepower now when compared to before the GFC, and fiscal policy is also limited in some countries. Interest rates are typically much lower now than pre-GFC while central bank balance sheets are much larger, potentially limiting QE. Prospects for fiscal policy are also limited in economies with high debt levels. The U.S. government’s debt-to-GDP ratio is about 107 percent, although in Europe it is lower at 85 percent. That is why many, including Mario Draghi’s successor Christine Lagarde, have called for stimulus in countries like Germany and the Netherlands.

CRU’s view is that both monetary and fiscal ammunition has been reduced, limiting the ability of policymakers to ease their way out of a recession. On China, our view is that the government is unlikely to undertake the type of large fiscal stimulus implemented during the GFC since China now faces the costs of its past stimulus in the form of debt build-up and credit risk. That said, our growth forecasts include expectations of further fiscal policy stimulus, worth RMB 2.5 trillion, or 3 percent of Chinese GDP. We expect these measures to be announced at the National People’s Congress in March 2020.

Trade War is a Threat to the Managed Slowdown in China

In Q3 2019, Chinese GDP expanded by 6.0 percent, the slowest rate of growth in 27 years. The outturn was also at the bottom of the government’s full-year growth target of between 6 percent and 6.5 percent in 2019. We expect growth to slow further to 5.8 percent in 2020 and 5.6 percent in 2021.

The authorities have been deliberately engineering a deceleration in growth for nearly a decade (pre-dating the trade war). They have done so with a recognition that the double-digit growth rates witnessed before 2008 are unsustainable and undesirable, as they led to a poor environment and stoked financial vulnerabilities. As such, policymakers have been focusing on the quality of growth over the speed of growth. This focus has been accompanied by policies to control credit growth and reduce pollution levels, e.g. “winter heating cuts.”

The trade war with the U.S. has sparked widespread concern that the managed slowdown will be pushed off track. It has also created uncertainty about how Chinese policy might respond. The issue is whether the current pace of slowdown is overshooting what the authorities were aiming for. Our view is that global growth over the next five years will be marginally lower due to the trade war, partly because the government has successfully offset some of the trade war induced growth weakness with fiscal stimulus. Whether the government can continue to follow such a strategy, and deliver its managed slowdown, remains to be seen.

Trade War and Populism an Ongoing Drag on Global Growth

In 2019, global growth has turned out to be weaker than expected. The outlook for 2020 has also been downgraded since January. The IMF has described prospects for 2020 and beyond as precarious. Our view is that the fundamental forces that will shape global growth in coming years include the slowdown in China, the trade war and populist policies, as well as monetary and fiscal policy easing. Our view is that the current trajectory of the trade war and populism are acting as a drag on global growth. We judge that these forces will persist for a while still, but if history is anything to go by, these factors can and do change over time.