Market Segment

December 7, 2019

CRU: China in 2020--Government Spending to Play Larger Role

Written by Jumana Saleheen

By CRU Chief Economist Jumana Saleheen, from CRU’s Global Steel Trade Service

This piece sets out insights gained from a visit to CRUs Beijing office. The trade war has been an unexpected headwind to China’s economy and there is a real concern about the risks of a sharper than desirable growth slowdown. In response the government is expected to announce further stimulus (which is already built into our forecasts) to ensure nothing less than only a gradual slowdown in GDP growth. But we now expect much of that stimulus (around four-fifths) to come in the form of central and local government spending rather than tax cuts. This is net positive news for commodities demand. Monetary policy will also play a greater role next year, as headline inflation rates ease.

During my visit to CRU’s Beijing office in early December, I was able to tap into the knowledge of my colleagues and their extensive network. I have drawn on those conversations to set out what policies and targets to expect from the annual Economic and Work Conference in mid-December (dates not pre-announced).

December Economic and Work Conference

Each year, the Chinese government sets out its plans for the economy in the following year at the December Economics and Work Conference. This is a three-day conference which occurs at some point in mid or late December, the exact dates are not pre-announced. Last year the meeting took place during Dec. 19-21. Typically, one can expect information about the target growth rates for GDP and employment growth (announced at next March’s NPC assembly), as well as plans for fiscal and monetary policy where the toolkit is larger and typically more complex than in western economies.

Economic Backdrop: Longer, Broader Trade War the New Norm, But a Poorer Outlook Exists

Compared to 12 months ago, the chatter regarding the negative impact of the trade war was a little lower, partly because many were resigned to the fact that the trade war was here to stay, and they just had to accept it and move on. There were two broad views. One group remained concerned that the trade war would carry on for longer and morph into a much broader “de-coupling” of China from the U.S. This would be beyond trade and technology to capital and labor markets that would reduce knowledge sharing and likely reduce marginally the outlook for productivity growth, thereby slowing the pace of transition of China from a middle-income economy to a high-income economy. This was in line with CRU’s view. Domestic vulnerabilities in China were also worrying—namely the recent sharp rise in household debt levels—which as a share of GDP are now as high as the UK. Not everyone was this pessimistic. The optimists pointed to the impressive level of innovation and high tech in China (e.g. 5G and Huawei) – also highlighted by the IMF. For this group, the trade war impact would be minimal in the longer-term context.

Downturn Pressures on Private Spending from Q2 of 2019.

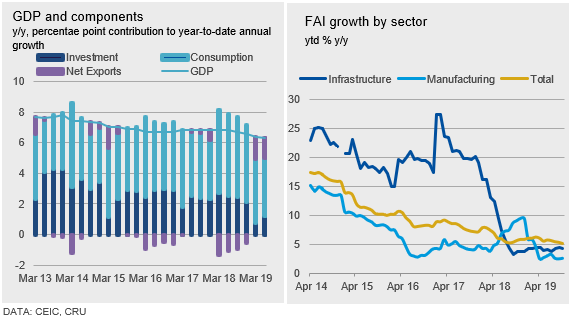

The chart below shows the contributions to GDP growth. What is evident is that the contribution from private sector spending—that is investment and consumption—has fallen quite sharply over the past two quarters (Q2 and Q3). This weakness in private sector spending is an area of concern in China because it means that the domestic economy is slowing. The contribution from net trade had turned positive in recent quarters, where import growth has fallen by more than exports. The weak imports were another signal of weak demand in China.

The investment component of GDP is known to correlate strongly with fixed asset investment (FAI). FAI growth has declined through 2019, with significant declines in manufacturing (related to the trade war) and infrastructure related to deteriorating local government fiscal position caused by sluggish land sales, tax revenue and less profitable infrastructure projects due to previous build-up.

The perceived risk going forward was that the softness in the domestic economy could deteriorate if consumer and business confidence weakened further (thereby sparking an unfavorable negative feedback loop). Policies that would boost confidence would therefore be needed sooner rather than later.

GDP Growth Target for 2020 to be Lowered to “Around 6%”

China has multiple economic targets. While China’s GDP growth target gets a lot of attention particularly from the West, internally, the employment growth target is of equal if not greater importance for social stability, especially during economic slowdown. It is no secret that Beijing has multiple economic targets. In China, these are captured by what the authorities have called the three grand battles—a good environment, financial stability, and poverty reduction. The employment target is crucial to the final battle—raising living standards and reducing poverty.

Employment is Crucial to Reducing Poverty and Raising Living Standards

The governments employment target for 2019 was to create 11 million new urban jobs. Data showed that employment growth to October was 11.93 million jobs, therefore the full-year target has already been met. Looking forward, there were concerns that the outlook for jobs growth was weakening. Pressures were obvious in manufacturing industries hurt by the trade war, and in industries where capacity cutbacks had been put in place (e.g. steel). At the State Council’s executive meeting on Wednesday, Premier Li Keqiang said, “We will face even greater risks and challenges next year. We must give higher priority to keeping employment stable as this is the key in ensuring that our economy does not slide out of the proper range.” The government will intensify support to businesses to keep their payrolls stable. For example, CRU has heard anecdotally, suggestions that some businesses were being offered a bonus to retain workers.

Economic Growth that Slows Gradually

Beijing is set to meet its GDP growth target—of “6-6.5%”—for the full year 2019.

What about next year? CRU expects growth to fall to 5.8% in 2020, and this forecast includes our expectations of further fiscal and monetary stimulus in 2020. The Bloomberg consensus GDP forecast is also 5.8% in 2020. Our view is that 5.8% growth next year is acceptable by the government. One might infer that the growth could be lowered to 5.5 to 6%. But we don’t think that will be the case because 6% GDP growth is seen by many as a psychological threshold. Instead, we expect the growth target to be “around 6%.” This serves the dual purpose of boosting confidence in the economy, and allowing the target to be met, even if the growth outturn was 5.8%.

Limited Room for Fiscal Easing; Stimulus to Come Mainly Through Government Spending

We expect additional fiscal stimulus in 2020, with the total stimulus package to be a little smaller than last year. But we now no longer expect the bulk of that stimulus to come via tax cuts as it did last year (where two-thirds came via tax cuts and one-third via government spending). Instead, we expect four-fifths of the stimulus to come via government spending. This change in our view is net positive for commodities demand.

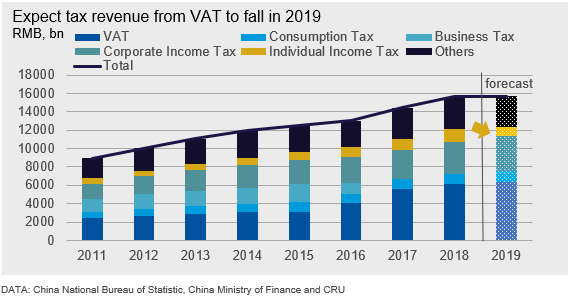

The change in our view is justified for two reasons. First, there is just much less scope to cut taxes. The RMB 2.4 trillion cut in taxes in 2018-2019 has led total tax revenues to rise by a modest 0.4% in the year to October. This flat profile for tax revenues constrains government spending. Secondly, as the downside risks to growth have increased, there is a desire to return to tired and tested means of fiscal stimulus—government spending—which is known to have a larger and more direct impact on growth (a larger fiscal multiplier).

Local Government Special Bonds Quota to Rise in 2020 and Frontloading to FY 2019 Allowed

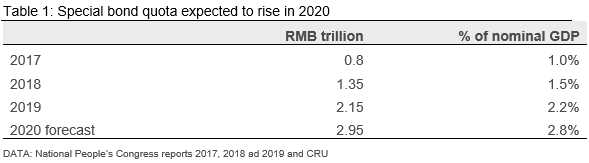

Local governments (LG) undertake the bulk of public infrastructure investment in China and are responsible for around 85% of total government spending. The extent to which local governments can spend on new infrastructure projects is determined primarily by the funds they can raise through the issuance of special bonds. In the past two years, we have seen the annual special bond quota rise in both nominal terms and as a share of nominal GDP; we expect the same to occur again in 2020 (Table 1).

This is net positive news for construction and infrastructure spend and for demand for steel long products. Like the previous two years, we expect LGs to be able to start issuing those funds from January 2020, that is before the start of the next financial which starts in April 2020. That will ease funding constraints on LGs who have pretty much used up their annual quota. In November, the government lowered project capital ratio (like capital down-payments) for infrastructure investment from 25% to 20% to permit higher leverage. And for some low-risk and profitable projects in areas of weakness such as railway, road, environment protection, wellbeing of the general public, the project capital ratio can be cut further by up to 5%.

Targeted Infrastructure Spending on Rail and Subways

The government spending will be targeted to areas that are high on the agenda of the people, such as improved transport and infrastructure. This will include improving commute times between cities (inter-city railway links) as well as within cities (subways and charging infrastructure for electric vehicles). This is part of the broader Chinese policy to build city clusters, a good example of President Xi’s vision to build and connect the city of Xiongan to create the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebie triangle. Infrastructure spending will also have a regional focus, e.g. more rail spending in Western (Tibet/Xinjiang) and Northern provinces (e.g. building intercity railways between cities located at the Yangtze River Delta). In the property market, greater renovation of old houses is expected.

Monetary Easing Targets Investment Not Property, Improving the Monetary Policy Framework

This year, China has been active in reviewing and enhancing its monetary policy framework. In the past, the Peoples Bank of China (PBC) has influenced bank lending rates through a variety of monetary policy tools—particularly by setting benchmark interest rates, such as the one-year rate. In August, the PBOC announced that going forward it would like to measure the degree of monetary easing based on the Loan Prime Rate (or LPR). The LPR is set by banks, but the PBC will seek to influence this rate via short-term repo and the Medium-Term Lending Facility (MLF). Banks are incentivized to maintain the LPR, as it will be used for regulatory purposes. This rate was reduced each time by a mere five-basis points on Sept. 20 and Nov. 5.

Room for Monetary Easing – Expect RRR Cuts and LPR Cuts of 20bps in 2020 H2

There is widespread agreement that China has more room to ease monetary policy. China has not cut interest rates much this year (just the 10bps noted above), because inflation has been above the inflation target of around 3%. Monthly CPI rose to 3.8% y/y in October, from 3% in September. The main driver has been food prices (particularly persistently high pork prices that have followed from another outbreak of African swine fever in Gansu). But inflation is expected to drop back in the second half of 2020, as the higher level of food prices fall out of the inflation calculation. At that point, when inflation falls below the inflation target, the PBC are more likely to feel comfortable making additional interest rate cuts. Our base case view is around 20-25 basis points in the second half of 2020.

There is always a concern that the rate cuts could lead to upwards pressures on property prices, which we know President Xi wants to avoid, given the adverse impact of the boom-bust property cycle they had witnessed in countries such as Japan. But the view on the ground was that for small rate cuts this risk could be controlled via a range of quantity restrictions including apartment quotas per family in some cities and provinces, as well as bank credit restrictions.

Four-fifths of Additional Stimulus to Come via Government Spending

Our narrative for China is that the authorities want a trajectory for growth that is stable and sustainable as the economy transitions from a developing to an advanced economy. The trade war has been an unexpected headwind to that broader plan, and it threatens a sharper fall in growth than is desirable.

During my trip, I sensed a real concern that employment growth and private sector spending and confidence was weaker than expected in 2019. The risk of a further sharp slowdown in 2020 had increased significantly. As such, there was a need to act now through modest additional stimulus, not aimed at lifting growth, but instead to halt further falls in confidence and ensure nothing less than a gradual slowdown in GDP growth.

To ensure stimulus has maximum impact, it would require Beijing to revert to its “old ways”: stimulus via government spending on infrastructure and construction, rather than tax cuts as was done in 2019. And, while stimulus in 2019 was largely through fiscal easing, in 2020 monetary and fiscal policy would have to work together.

These insights have led us to revise our view. We now expect around four-fifths of the RMB 2.5 trillion stimulus that is baked into our 2020 macro forecast to come via government spending rather than tax cuts (previously we had called for 1/3 to come via government spend and 2/3 via tax cuts).

2020 is likely to be a critical year for China. Not only will there be continued focus on the headwinds from the trade war and rising domestic vulnerabilities, there will also be focus on whether the economy was able to deliver the promise made during the previous two five-year plans to achieve a “moderately prosperous society” (Xiaokang). All eyes turn to the year of the Rat, which begins on the Chinese New Year of Jan. 25.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com