Market Segment

February 23, 2020

CRU: How is Covid-19 Affecting China’s Steel Production and Exports?

Written by Paul Butterworth

By CRU Research Manager Paul Butterworth and Analyst Zhenzhen Jiang, from CRU’s Global Steel Trade Service

The loss of steel demand from Covid-19 has pushed Chinese steelmakers to either reduce utilization or idle capacity but, as steel stocks at mills reach critical levels, they will increasingly seek to offload in the export market. Decisions by mills will be dictated by the processes they are operating (EAF or BF/BOF), location of the mill and cost competitiveness, as well as more prosaic considerations such as physical space. EAF producers are most likely to idle capacity, possibly due to the flexibility of their operations, but more likely because scrap is simply not available as collection will be impacted by a lack of trucking capacity and workers. However, integrated mills will have less flexibility and are likely to be coming under more pressure to export steel or sell at low prices domestically to move material into trader stocks.

Crude Steel Production Will Fall by 37 Mt

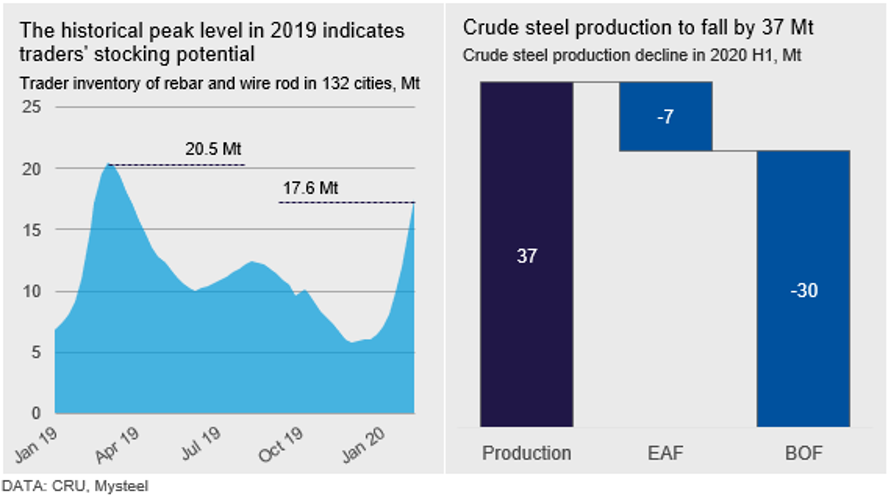

As steel stocks at mills reach critical levels and demand remains constrained, mills are expected to cut their production further in the following months and, in our base case, we expect steel production to return to normal levels only by end-April, following a recovery in demand. This will result in steel output falling by 37 Mt in the first half of the year. Output from BF-BOF producers accounts for 30 Mt of the fall, with the remainder coming from EAFs.

The combination of weak demand and difficulty in collecting scrap has forced most BF-BOF producers to lower scrap usage. These producers have also brought forward maintenance programs that traditionally last for 15-20 days. Some mills have also run out of storage space for inventories, forcing them to rent additional space or limit production. Therefore, we expect further production cuts from BOFs in the near-term. Monthly capacity utilization is likely to reach a low point of ~65 percent in March.

• EAF Production: While independent EAFs are expected to remain halted, more integrated EAFs are expected to cut output, facing the challenge of financial pressure. Moreover, due to low margins, high-cost EAFs will remain shut until margins rise. As such, the capacity utilization rate of EAFs will remain below normal levels after entering April.

• Blast Furnace Production: BF-BOF producers have lowered scrap usage that has partially offset the impact of a fall in crude production on BF operations. Our model suggests a scrap loss of 3 Mt across the BF-BOF sector between February and April, leading to a net decrease in hot metal of 32 Mt over the same period.

We expect a total gap of ~24 Mt between steel supply and demand from February to April, which will need to flow into the export market or domestic inventory.

The additional inventory could, ultimately, be consumed by higher demand due to possible stimulus, lower production or a combination of the two after demand recovers from end-April. Historical inventory levels suggest that traders have potential to absorb additional steel inventory and, in the near term, are likely to take advantage of low offers from mills that are under pressure to sell due to limitations of space and cashflow, and sell to end-users after demand picks up.

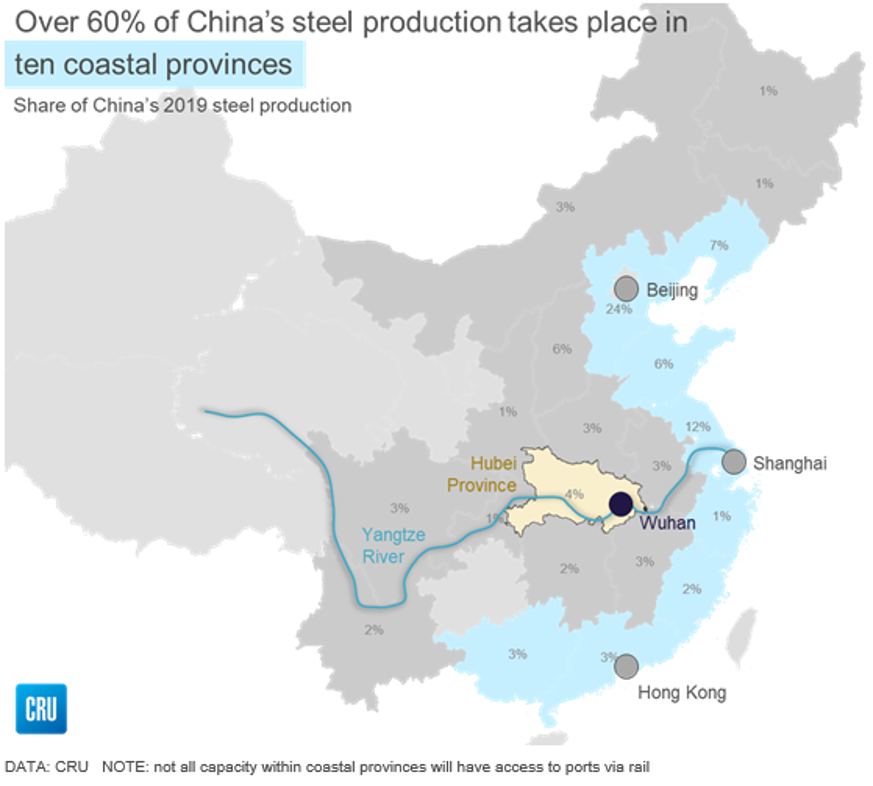

Coastal Mills Will Turn to Export Market

Regardless of steelmaking process, mills further inland will not necessarily have access to export markets due to logistics (trucking) constraints and will need to reduce output or idle capacity in the first instance. Lower cost coastal mills are therefore more likely to turn to export markets, particularly those that have access to ports via rail, which is currently operating more effectively than truck transport. Indeed, the current reduction of the spread between domestic and export steel prices in China is indicative of the restrictions on many mills that only have access to a poorly performing domestic market and limited number of [coastal] mills that can export.

Our modelling suggests that, if all demand lost in all provinces were instead exported, then exports could rise by 5–12 Mt/month under our best and base case. However, a number of considerations suggest that this figure for additional exports will not be reached and so it should be considered an upper bound.

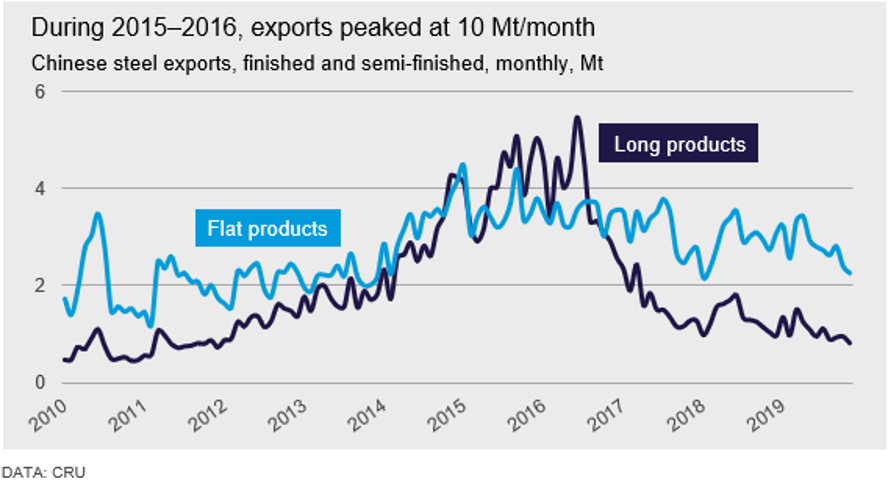

Firstly, provinces are not equally affected by containment measures as some of the more significant measures have been enacted in inland areas and away from ports—for example, in the epicenter of the outbreak, Hubei. Steel mills in these regions will simply be unable to transport the steel to an export terminal. Secondly, reductions to steel production will reduce the net amount of lost steel demand available for export and, thirdly, there may be insufficient port infrastructure to support the movement of all lost demand, particularly during the worst affected period in early March. Using a proxy of the severe downturn through end-2015 and into 2016, exports peaked at ~10 Mt/month, equivalent to ~2.5 Mt/week. At that time, labor and logistics were not as reduced as they are currently. As 4.0 Mt/month is currently being exported on average, this suggests that the maximum uplift to export volumes due to the loss of demand is ~6.0 Mt/month, or ~1.5 Mt/week.

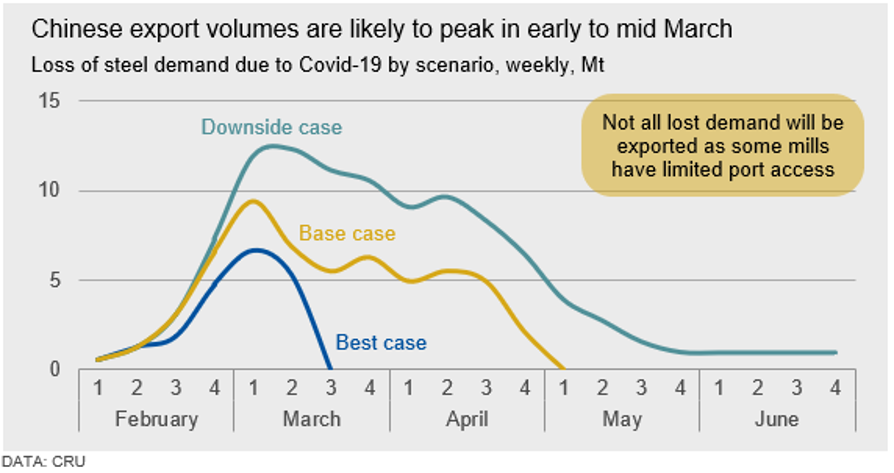

Exports to Peak in March

Our modelling suggests that the pressure on mills to export will not be the same throughout the affected period. Indeed, as the chart below shows, the loss of demand in the first three weeks of February (up to and including this week) is not that significant, as demand was already expected to be low following the CNY holiday and mills would have been, at least partly, prepared for this. However, as we enter the last week of February and move into March, the net loss of demand widens substantially, reaching a high in the first week of March, but remaining elevated through to mid-April. This suggests that the pressure to export will be greatest through early-March, but could remain elevated for the following month before receding again.

Overall, although the total loss of demand and port capacity limitations imply that Chinese export volumes could rise above normal levels by up to ~17 Mt in total for the affected period (i.e. February to June), the profile of the demand loss, production decreases, and potential to build trader inventories suggest that it is likely to be lower than this level at ~10-12 Mt. While we assume the maximum export volume cannot be achieved in March or April, as port capacity it limited, additional export volume in these two months will be ~3-4 Mt/month. The remaining 4 Mt of additional exports will leave the country during the period May-June.

In terms of which mills might start to export, the larger demand centers of coastal cities that are not directly affected by the outbreak will still face a delayed restart of end-use activity due to migrant workers being unable to return from rural areas. In turn, this will dampen steel demand along the coast and force mills there, that have better access to ports, to turn to export markets. Indeed, we have already assessed that Chinese offer prices for steel have fallen and are now very competitive with other exporters. In addition, the bulk of the transactions we are aware of so far are linked to coastal mills.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com