Analysis

November 10, 2023

Ferrous Scrap: The Iron Foundry Market

Written by Stephen Miller

The iron and steel foundry industries consume about 17% of the ferrous scrap in the US each year. They purchase several grades of scrap in common with steelmakers, such as shredded and turnings. But, most of the grades are much more restrictive than what larger mills require.

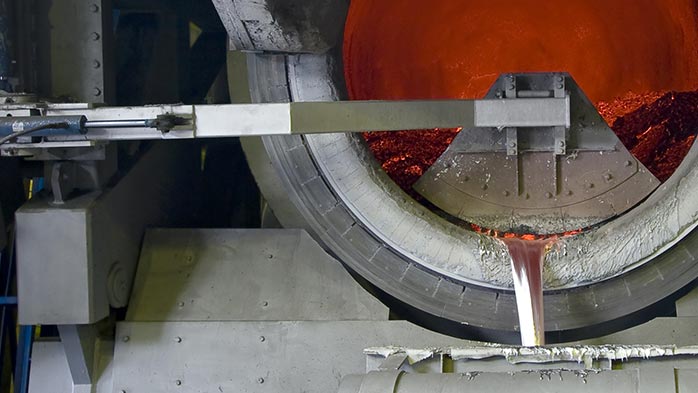

Today, the majority of steel mills use the electric-arc furnace (EAF) to manufacture steel. However, most foundries use an electric induction furnace (EIF) to melt scrap and convert it into iron or refine into steel. These EIFs are smaller and can only process certain grades and sizes of scrap. The same goes for the cupola furnaces still operating.

So, one main difference is scrap size. The vast majority of foundries insist on all scrap they purchase be under 24” in length, some even demand 18” max. This is true for busheling, punchings, plate and structurals (P&S), and cast-iron scrap. Most mills, on the other hand, have a specification on length of 60” and under. So, these grades are two different animals.

Since it is more costly to prepare or segregate material to comply with the tighter foundry specifications, the sales price is vastly increased over what steel mills buy.

Another difference is chemistry. Because of their larger melt size, steel mills can afford a much looser specification for the chemical profile of the scrap they buy. Not that this is very liberal by any means. But it is far less rigid than what most foundries ask for. Steel mills make steel, but most foundries make iron castings, which are used for parts for cars, trains, and planes. They have to be perfect. For instance, on Manganese (Mn) content, most mills have a specification of 1.65% and under. For foundries making gray iron casting, their busheling spec for Mn is usually 0.60-0.90%, whereas ductile foundries are usually 0.40% max. This limits the universe from where a supplier can source scrap. To get steel scrap with 0.4% max Mn, you can’t use 80% of SAE 1000 Series steels.

A third difference is coatings. Over the last several decades, steelmakers have had to accept scrap with coatings such as galvanized and zincrometal. They had to install expensive anti-pollution equipment to be able to melt these grades, as protective coatings became required by the automobile industry. Not so with foundries. They require zero coatings for the industrial busheling they melt. They just could never afford the anti-pollution equipment. So, they insist on uncoated, “black” scrap without excessive oil or painted stock. Needless to say, this type of material is hard to come by and is much more expensive.

To give some of you scrap generators the price differences between mill scrap and foundry scrap, let’s take a few examples.

For November, on an FOB truck delivered Toledo, Ohio, basis here are the prices of mill grades vs. foundry grades, in gross tons:

| #1 Busheling | Mill grade (60”L) | $425 |

| Low Mn Foundry grade (24”L) | $505 | |

| Plate & Structural | Mill Grade (60”L) | $385 |

| Foundry grade (24”L) | $435 | |

| Auto Cast Iron | Mills usually don’t buy separately | |

| It’s mixed in with shredded | $395 | |

| Foundry grade | $465-480 |

As you can see, the premiums are $50-85 per gross ton (GT).

According to Mark Fritts of Fortify Trading, the projections are this gap will widen in the not-too-distant future. The labor involved in processing scrap continues to rise. Also, it’s harder and harder to obtain low Mn busheling with the alloys now in low weight, high-strength steels being used by the automotive industry. Fritts added, “These quality grades of scrap are on a continual decline.”

Another source had prices of this grade as high as $520 per GT. He mentioned the United Auto Workers (UAW) strike had not hurt his overall supply.