Government/Policy

January 7, 2020

Fed Study Refutes Benefits of Trump Tariffs

Written by Sandy Williams

A recent study by the Federal Reserve concludes that the Trump administration tariffs are doing more harm than good to the U.S. economy and manufacturing.

Federal economists Aaron Flaaen and Justin Pierce examined the impact the “unprecedented” number of tariffs imposed under the Trump administration have had on the U.S. manufacturing sector.

Escalation of tariff activity began in February 2018 when President Trump used Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974 to impose tariffs on imports of large residential washing machines and solar panels/modules.

The second major tariff action was imposed to protect the U.S. steel and aluminum industry from imports using Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. According to Commerce findings, such imports threatened U.S. national security. The 25 percent steel and 10 percent aluminum tariffs set off a backlash of retaliatory measures from the EU, Canada, Mexico and China.

The third major tariff was imposed against China based on Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 and was carried out in several phases by the administration. Focusing first on Chinese trade practices associated with intellectual property and technology, tariffs eventually targeted a wide range of imported goods. Phase 1 and 2 tariffs were imposed in July and August placing 25 percent tariffs on a combined $50 billion of goods. Additional tariffs were imposed at a rate of 20 percent in September 2018 covering $200 billion of Chinese imports. China retaliated with equivalent value and rates for Phases 1 and 2 and a milder retaliation for Phase 3 covering $60 billion of U.S. imports at rates ranging from 5 to 10 percent.

Although the administration boasts about the revenue received from tariffs, the true cost is paid by U.S.-registered importers who pass tariff costs on to manufacturers and consumers, say economists.

Flaaen and Pierce found that the tariffs resulted in reductions in manufacturing employment and higher costs for producers. The protection that the tariffs provided to domestic producers was more than offset by rising input costs and retaliatory tariffs from U.S. allies.

The study also found that the use of trade policy as a tool for the protection and promotion of domestic manufacturing is complicated by global supply chains.

“We find the impact from the traditional import protection is completely offset in the short-run by reduced competitiveness from retaliation and higher costs in downstream industries,” said the authors.

“While the longer-term effects of the tariffs may differ from those that we estimate here, the results indicate that the tariffs, thus far, have not led to increased activity in the U.S. manufacturing sector,” concluded Flaaen and Pierce.

The latest manufacturing index from the Institute for Supply Management supports the findings of the study. The ISM Manufacturing PMI posted its lowest reading since June 2009 and marked the fifth month of contraction for the sector.

Federal Reserve officials are expecting manufacturing production to remain weak, at least in the short term, according to minutes from the final Federal Reserve meeting of 2019.

“Manufacturing production appeared likely to remain soft in coming months, reflecting generally weak readings on new orders from national and regional manufacturing surveys, declining domestic business investment, slow economic growth abroad and a persistent drag from trade developments,” the Fed said.

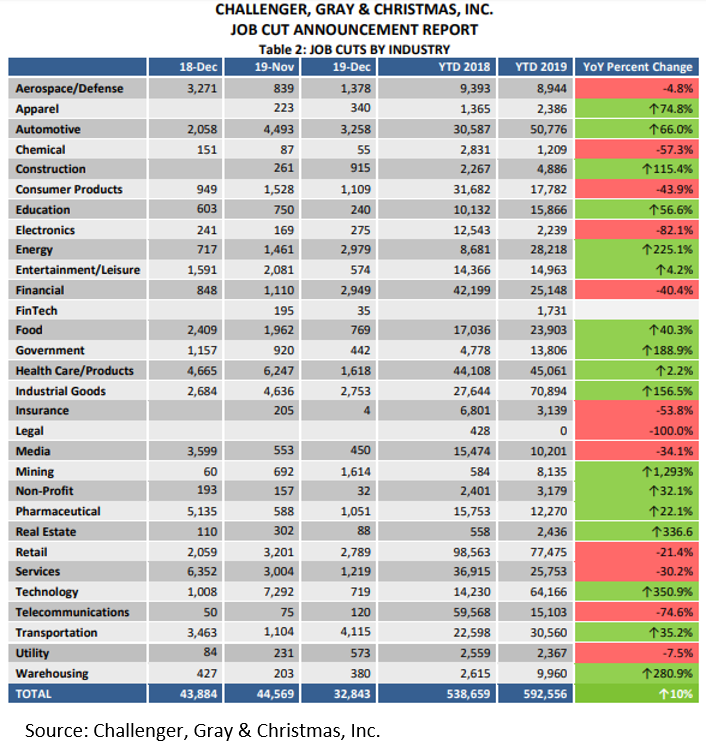

Although the U.S. has enjoyed low unemployment, a study by Chicago outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas revealed that employers eliminated 592,556 jobs in 2019, 10 percent than in 2018 and the most in four years. The primary reason was bankruptcy or restructuring with trade difficulties cited for 11,688 job cuts and tariffs for 5,881.

Industrial goods manufacturers cut 70,894 jobs, up 156 percent from 2018, while job loss in the automotive industry went up 66 percent to 50,776 jobs.

“The sectors with the highest number of cuts this year were all dealing with trade concerns, emerging technologies and shifts in consumer behavior,” said Challenger.

In the steel industry, steelmakers have reported declining financial results this year due to lower demand and prices, reduced forecasts for 2020 and closed or idled facilities, despite the protection from steel imports under Section 232 tariffs. U.S. Steel will lay off more than 1,500 employees beginning in April.

IHS Markit Chief Business Economist Chris Williamson commented on business sentiment in the December IHS Markit U.S. manufacturing survey: “Business sentiment about the outlook remains especially subdued compared to a year ago, reflecting ongoing worries about geopolitics and trade wars, especially the impact of tariffs, as well as fears that political and economic uncertainty surrounding the 2020 elections could dampen demand. The impact of tariffs was clearly evident via higher prices, while the relatively subdued level of business confidence manifested itself in a pull-back in hiring, hinting at risk aversion and cost-cutting.”