Analysis

December 10, 2023

Leibowitz: Steel and aluminum intensity—the trade implications

Written by Lewis Leibowitz

This year saw a huge increase in debate and proposals for addressing greenhouse-gas emissions, not only here in the US but around the world.

All the angst about a climate catastrophe, including rising sea levels, more intense and frequent hurricanes, etc., has not led the world closer to an effective program to do something about it. The global climate conference (COP 28 in Dubai) reflects that reality. While many world leaders are attending, China’s President Xi and US President Biden are not.

Each country has its agenda for addressing climate change. Those policy responses, here and elsewhere, reflect the interests of each country’s government and private-sector participants. The divide between authoritarian regimes and democracies also reflects these differences. Authoritarian governments promote their strategic ambitions more effectively than global interests, such as addressing climate change.

Where you stand depends on where you sit

In the US, the response fits the interests of its politicians and private interests. The International Trade Commission is currently studying, at the request of the Biden administration, the “carbon intensity” of steel and aluminum production. The Commission conducted a hearing on Dec. 7 on this issue. A report on the steel and aluminum industries is due in January 2025, after the next presidential election. This does not reflect a sense of great urgency and crisis. Nor does the inability of the US and EU to agree, after two years of talking, on a common response to the global challenges of steel and aluminum.

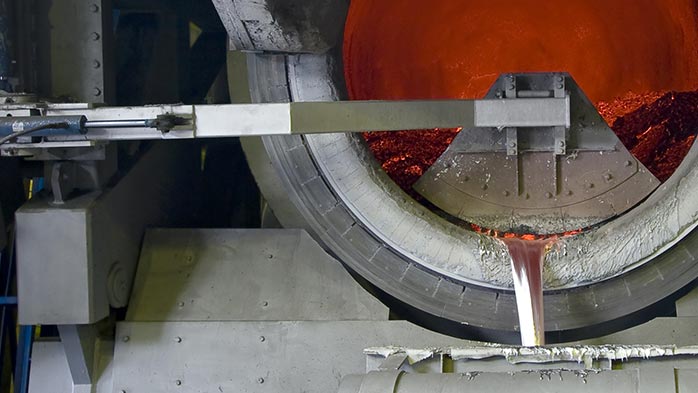

The steel industry is mostly united, but some gaps in policy are starting to appear. Steel production is of two basic types: a basic oxygen blast furnace (BOF) and an electric-arc furnace (EAF). The US has embraced EAF production to a greater extent than any other major steel producer. As a result, the US can justly claim to be at the forefront of “clean steel.” This is because EAF production produces lower carbon emissions than BOF production.

Pioneered by Willy Korf (direct-reduced iron and scrap as raw materials for steelmaking) and Ken Iverson, the founder of Nucor, EAF steelmaking has largely taken over steel production, and has completely captured the construction of new steel mills in this country.

BOF has its advantages, both commercial and political. First, certain grades of steel (armor plates for ships) and high-technology flat-rolled steel (such as tin mill products) are not practical for EAF mills. Second, BOF mills are monuments to heavy industry, employing thousands of workers and providing votes for their members of Congress. The United Steelworkers union has overwhelming support from BOF mill workers, but few EAF workers are members.

BOF steel production has completely replaced open-hearth production that held sway from the 19th century until after World War II. It is a major improvement over open-hearth technology.

But BOF production is not as clean from a climate point of view. It requires carbon to separate iron from oxygen. When that happens, the result is CO2! End of chemistry lesson. CO2 is disposed of largely through chimneys, spewing large amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere.

The advantages of EAF production are quite different. EAF started with “long” products, meaning rails, bars, wire rod, I-beams, etc., because the purity of steel scrap was not suitable for making flat-rolled steel (plate and sheet). But since about 1990, Nucor and others have expanded into flat-rolled steel. Largely for this reason, EAF steelmaking now is nearly three-quarters of US production.

EAF production is significantly less carbon-intensive than BOF. Recent estimates peg BOF production at about five times the carbon intensity of EAF production. This is the most important reason the US can claim the “clean steel” title. The rest of the world still mostly uses blast furnaces.

The domestic steel industry has two principal trade associations that speak to the issue of reducing carbon emissions—the EAF sector is often seen speaking through the Steel Manufacturers Association (SMA) and the BOF sector through the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI). Both are effective and have developed many policy proposals jointly.

Regarding restricting international trade in “dirty” steel, they propose that the US hit such steel with tariffs based on a benchmark that, domestically, only EAF mills meet. But the tariff would protect BOF and EAF production in the United States.

But cracks are appearing. In government procurement, for example, the agency charged with overseeing the construction of nonmilitary government buildings and infrastructure (GSA) proposed “clean steel” regulations setting a more lenient emissions standard for BOF-produced steel than for EAF steel, based on the production capabilities of the two sectors (and based, clearly, on political considerations). But SMA advocates a single standard, which would benefit EAF mills and set BOF mills back.

The reason behind the “double standard” published by GSA has more to do with domestic politics than cleaning the air. According to a recent survey, there are only 10 BOF steel mills in five states (Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, and Pennsylvania). By contrast, the US has 83 EAF mills in 28 states. One of the two BOF mills in Illinois, U.S. Steel’s Granite City, idled iron- and steelmaking last month “indefinitely,” at the cost of hundreds of jobs. That mill was constructed in 1897.

Politically, closing a steel mill is a bitter pill. On average, BOF mills employ many more people than each EAF mill and have generally been around for many decades. Politicians will do almost anything to keep them up and running, including things that only postpone their inevitable closure for a few years.

Reducing carbon emissions in steel and aluminum is a worthy goal. A viable global solution is elusive at best. But the government wants to appear capable of handling it because many in the electorate believe that it is an existential threat to our planet.

The EAF and BOF segments of the US industry are not in lockstep, and things may get more divisive, especially if there are international agreements on carbon emissions. The trade impacts of such global agreements could further open the US market to cleaner steel from other countries.

Editor’s note: This is an opinion column. The views in this article are those of an experienced trade attorney on issues of relevance to the current steel market. They do not necessarily reflect those of SMU. We welcome you to share your thoughts as well at info@steelmarketupdate.com.