Product

September 10, 2019

SMU Summit: Three Distinct Views in the Debate Over New Capacity

Written by Tim Triplett

Do plans by U.S. mills to add millions of tons of new steelmaking capacity over the next few years make a price-killing supply glut inevitable? That’s a question very much open to debate, as shown by the spirited exchange between three leading analysts during Steel Market Update’s Steel Summit Aug. 28 in Atlanta.

Despite some pushback from the market, Timna Tanners of Bank of America Merrill Lynch is sticking by her prediction that “Steelmageddon” (a term she has trademarked) is coming and, like a runaway train, cannot be stopped.

Tanners said the many investments announced by the mills, including restarts, brownfield and greenfield projects, stand to add up to 20 percent more steelmaking capacity to the market from 2018-2022. The added production will displace some portion of the current imports, but not all, she said. And the recession predicted by many economists in the next few years could worsen demand and accelerate the price declines. She predicts the resulting steel glut will incite a price war as mills compete for buyers and could push the hot rolled price as low as $475 per ton. “We believe with Steelmageddon, the steel price will dip below the cost of production for the U.S. mills,” Tanners said.

Her prediction has raised eyebrows and prompted criticism from mill executives who maintain the market will be able to absorb the additional capacity due to higher steel demand and fewer imports.

Tanners is skeptical the mills can count on improved demand in a declining economy. Per capita consumption of steel appears to be shrinking. The automotive build rate is down, while vehicle designs use more lightweight high-strength steels, which means fewer tons. “There could be a big infrastructure push, but the money and the political will of the government are questionable,” she noted.

Many observers believe the capacity additions are overblown. They contend the mills are likely to replace some obsolete capacity with new facilities and are unlikely to follow through with all the investments they have announced. To that, Tanners counters: “There aren’t a lot of mills volunteering to be the ones to close capacity. Mills have deep pockets, and permanent closures are rare. A lot of these projects have the support and the financing and they are going to go ahead.”

She believes the U.S. will continue to be a target for imports. The planned capacity additions of 16-18 million tons, by her count, exceed the average annual net imports into the U.S. of about 14 million tons. “The U.S. imports more than any other market. Imports have remained stubbornly high despite Section 232. For imports to go to zero would be doubtful. Trading relationships don’t just disappear,” she said.

Tanners predicts the excess supply will disrupt not only the U.S. but also trade partners such as Mexico, Canada and Europe. Scrap prices could rise substantially, squeezing EAF margins. On a positive note, she added, consumers will win with both lower prices and greater quality and selection from their domestic suppliers.

“This will take some time. It could easily take five years to see the cycle play out,” Tanners said. “But prepare for the mother of all price wars. Mills do not shut easily and will not hand off market share for a smooth transition to new capacity.”

A More Nuanced Formula

Expressing some skepticism over Tanners’ predictions, panelist Lynn Lupori sees more nuance to the issue. Lupori is CRU’s head of consulting for North America. She believes the effect of the new capacity must be considered one mill, one market and one product at a time.

The formula behind any forecast for capacity additions must take into consideration closures, displacement and exits, she said. “Closures of existing facilities remain a real possibility as new capacity comes online.”

Each mill has its own risk factors to consider, such as how their capabilities and capacity align with the market’s needs; their cost competitiveness versus the new capacity; the importance of the facilities to the company’s portfolio; the availability and cost of feedstock material; and future investment required to even maintain the status quo.

Rerollers are one example of the type of player that is at risk because many require imported slabs, which are now subject to quotas or tariffs. “How cost competitive can these rerollers be if they have to bring slabs in from the outside? How are the duties and quotas going to limit their opportunity to compete in this market?” she asked.

Restarts of older capacity, such as U.S. Steel Granite City, JSW Mingo Junction and Liberty Steel Georgetown bring into question their positions in the market and their long-term viability. “Not to point fingers, but are they viable going forward, or are they likely some of that capacity we will see leave the market once again?” she said.

Displacement of imports is a significant opportunity and a driving force behind many of the mills’ investments. 2018 imports included 10.3 million tons of strip, 2.3 million tons of plate and 1.2 million tons of rebar. But replacing imports is not the full answer to the oversupply question, she said. “We can displace some of the imports, but we will always need some imports. There are things we simply don’t produce here or don’t produce enough of here.”

Some of the planned expansions are better positioned than others, strategically located near significant consumer markets or ports of entry. She pointed to three projects planned in Texas by JSW USA, Steel Dynamics and Big River Steel as examples.

Will all the new mills be built? Probably not, Lupori contends. “History has shown that even the best laid plans don’t always work out, especially in the steel industry. Delays are inevitable. Exits are possible.”

Much is uncertain, but not the following, she concluded: New capacity will place some level of pressure on prices. There will be an impact on the market share, margins, operations, etc., of some producers. And, agreeing with Tanners, consumers will be the ultimate winners in terms of prices, quality, timing and availability.

New Capacity: Oversupply or Overdue?

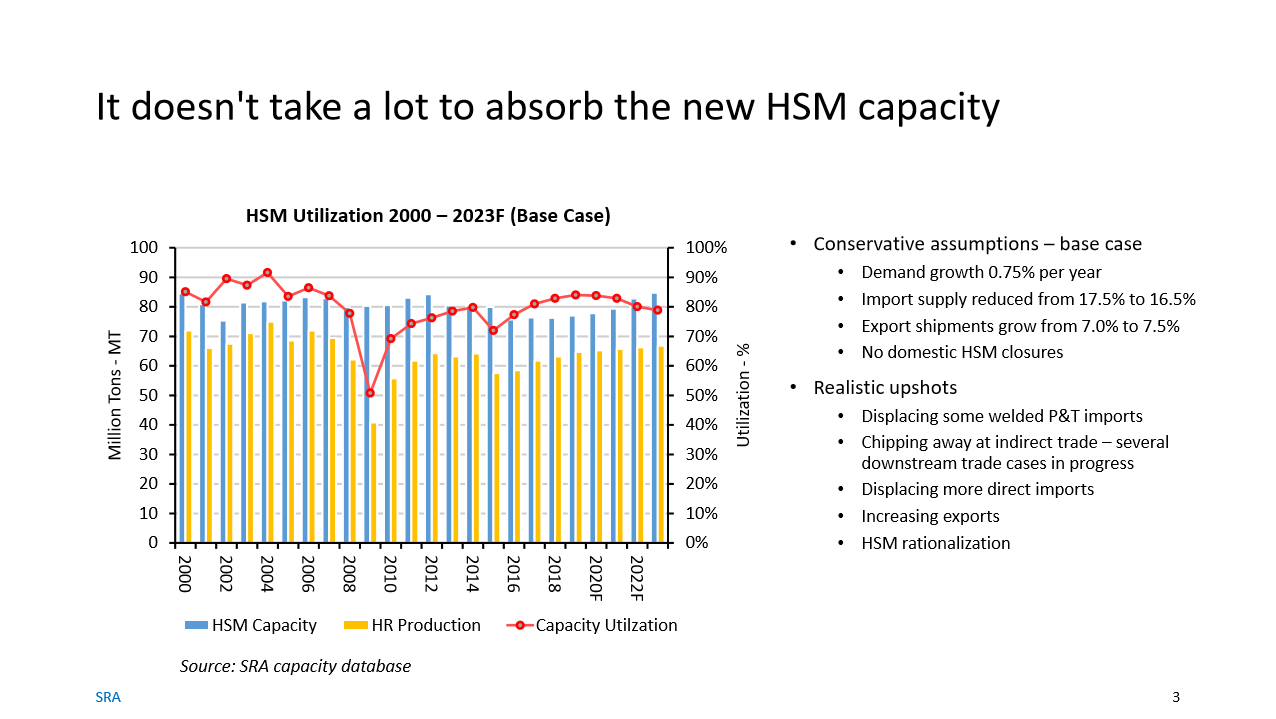

Panelist Paul Lowrey, president of Steel Research Associates, is the biggest skeptic of “Steelmageddon.” He believes strongly that the new flat rolled capacity, and the modernization of the domestic steel industry, is long overdue, not a guarantee of oversupply.

“I have looked at all the lists of capacity editions and I think there is some confusion between steelmaking capacity and finishing capacity. I think there has been some significant double counting of capacity,” he said. He estimates the total at closer to 13 million tons.

By his math, the market added 10 million tons of capacity and closed 10 million tons from 2000-2010, so there was no change. From 2011-2018, the mills actually retired 6.8 million tons of hot rolled capacity. Over the next 4-5 years, the mills plan to add about 6.9 million tons of new capacity. “In the decades from 2002 through 2023, there has been no change at all in hot strip mill capacity in the United States. What has changed is the technology,” Lowrey said.

The biggest technological change has been the shift toward electric arc furnace (EAF) production by the minimills and away from basic oxygen furnace (BOF) production by the integrated mills. In 2000, the market produced 84.6 million tons, 73 percent BOF and 24 percent EAF (with the rest no-melt or rerolled). As of this year, the integrated mills’ share will have declined to 53 percent, while the minimills’ share will have increased to 34 percent. Lowrey estimates that by 2023, BOFs will account for 48 percent and EAFs 40 percent, with no-melt at 12 percent, for a total capacity nearly the same at 84.7 million tons. “It’s the technology that’s changing, not the amount of capacity,” he asserts.

Flat rolled steel imports into the United States remain high by historical standards, even after the tariffs. In 2018, the U.S. saw direct imports of steel sheet totaling about 11.2 million tons. Imports of welded pipe and tube, which is made from steel sheet, totaled about 4.6 million tons. Indirect steel imports in the form of finished goods such as vehicles and appliances accounted for another 19.1 million tons. “In total, we imported about 35 million tons of sheet products last year. That is equal to 11 steel mills. Given that, it would not take a lot to absorb the new HSM capacity that has been proposed,” he said. He estimates that an annual improvement in consumption of just 0.75 percent, a 1 percent reduction in direct sheet imports and a half-percent increase in U.S. steel exports would free up enough demand for the new capacity to come without creating a price-killing oversupply.

“We just reduced corporate taxes; we have abundant energy sources; for the first time in a long time we are in a deregulatory environment for business. I think it is very realistic that you will see reshoring of domestic manufacturing, which will increase the demand for flat rolled steel,” he added.

On a cautionary note, he said the 13.0 million tons of planned capacity additions will strain the supply of high quality scrap. Scrap substitutes, such as DRI and HBI, will help fill the void, though at a higher price.

“Based on my analyses, I don’t believe the new flat rolled capacity is oversupply, I think it is long overdue,” he said. “These investments in new technology are required to keep the industry competitive.”