Market Data

January 16, 2020

CRU: Missiles Down, Sanctions Up – the Next Chapter in U.S./Iran Relations

Written by Ross Cunningham

By CRU Senior Cost Economist Ross Cunningham, from CRU’s Global Steel Trade Service

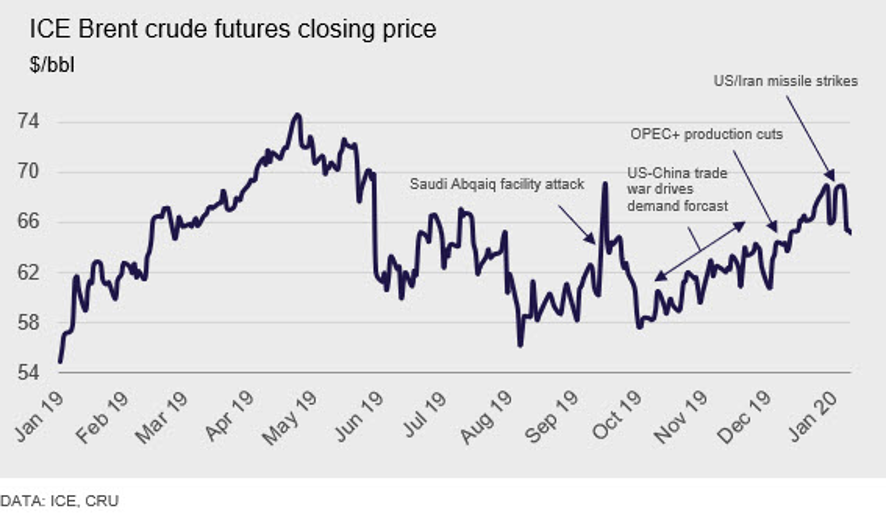

The oil market in 2020 started with a bang—multiple in fact, over the skies of Baghdad. On Jan. 3, U.S. missiles killed Iranian Major General Qasem Soleimani and four others. Iran vowed “severe revenge” and on Jan. 8 fired missiles at air bases in Iraq where U.S. forces were housed. Following the U.S. missile strikes, tensions between the two nations were high. The decision to target a high-ranking Iranian general was likely taken with the consideration that the U.S. is now much better placed in the global oil market thanks to U.S. shale. The retort by Iran was a gesture to save face and not an act to encourage war. The hostilities provide upside risk to our Brent crude forecast, but we do not believe the tensions will escalate. The U.S. does not want a war with an oil producer (albeit a small, sanctioned one) in an election year. And Iran does not want to pick a fight with the world’s largest military—especially when it has lost its secret weapon—the ability to hold the U.S. oil market to ransom.

In the wake of the U.S. strikes, Brent crude prices rose 6 percent to $70/bbl (a similar spike was seen in September 2019 with the Abqaiq processing facility attack in Saudi Arabia). The spike was due to a rise in the oil risk premium associated with fears of escalating Middle East tensions and repercussions for world oil supply. However, prices moved little after Iran struck back. It was clear the response was purposefully mild. Some speculate U.S. forces were forewarned of the attack to avoid casualties and thus an escalation. Since then much of the risk premium has come off as both parties have made clear they do not want an escalation.

This episode in Middle Eastern tensions feels very similar to the Abqaiq attack chapter—it started as an act of aggression, it did not escalate, it was resolved within a week and market participants turned quickly back to the moderate demand picture and its importance to where oil prices will go in 2020.

U.S. Oil Market is Self-Reliant…in Theory

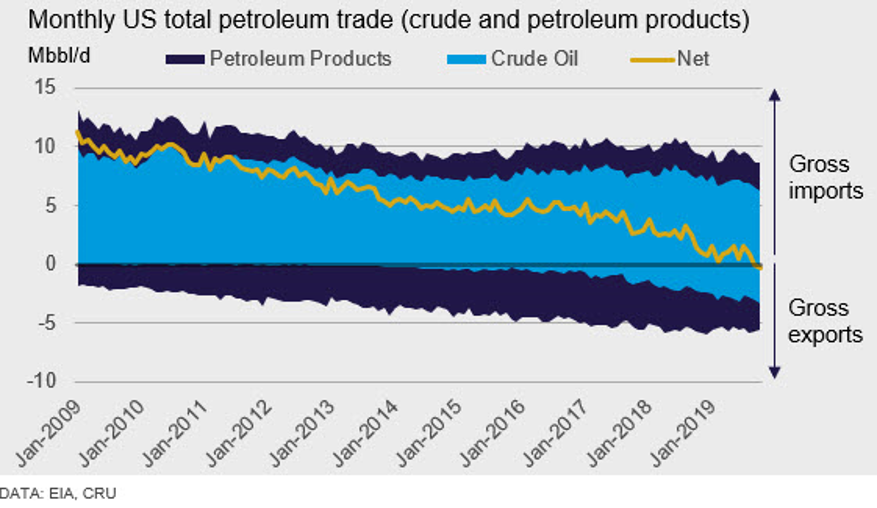

September 2019 was a momentous month in the U.S. oil market. It marked the point in time that the U.S. became a net exporter of crude oil and petroleum products. Ten years ago, the U.S. was a net importer of more than 10Mbbl/d of crude oil and petroleum products combined. This resulted in significant investment over the past decade in refineries to process heavy sour crudes from the likes of Canada, Mexico and Saudi Arabia. Since the explosion of the shale oil industry, the U.S. has become the world’s largest producer and has moved itself into a position of net exports. The U.S. still imports a lot of crude oil – 6.2Mbbl/d in September 2019 to be exact. This is because of that significant investment in refinery upgrades. The U.S. exports the majority of the sweet crudes produced from shale at a premium compared to the tar-like crudes it imports from Canada.

This has provided a strategic proposition for President Trump that his predecessors did not have. Now, being significantly less reliant on the Middle East for oil, any price rise driven by supply fears from the region can bring benefits to the U.S. on its supply side. But with 2020 an election year, the challenge for President Trump to aid a return to power is to keep gasoline prices acceptable for U.S. consumers.

This is fundamental in our belief that U.S.-Iran tensions will not escalate, at least from a U.S. perspective. Iran has different reasons why an escalation is not its best interest.

Make Sanctions Not War

The U.S.’s crude self-sufficiency means Iran’s strongest weapon—the strangle hold on the Strait of Hormuz—is blunted. The Strait is responsible for the transportation of ~20 percent of the world’s crude oil. This has allowed the U.S. to turn the screw on Iran through economic sanctions. The Iranian oil industry has been under U.S. sanction since May 2018. Despite this, it currently exports ~2Mbbl/d of crude to largely Asian destinations willing to continue business despite the sanctions, including China and India. The U.S. has now turned attention to the Iranian mining and metals industries, specifically the steel sector.

Seventeen of Iran’s largest steel and iron companies have been placed under economic sanctions. The measures grant the U.S. administration the ability to place anyone involved, even indirectly, with Iran’s mining sector or these companies on a global financial blacklist.

Iran has two moves left in its dwindling playbook. Advance to warfare against the largest and most powerful military in the world. This would always be a big step, but has become more so given the current anger of many Iranians towards the government following the botched cover-up of the accidental downing of a passenger jet on Jan. 8. Alternatively, interrupt oil movement through the Strait of Hormuz. As discussed, this may not harm the U.S. as much as Iran might desire and would furthermore damage relationships with Iran’s remaining oil buyers, notably China.

Beyond the Rhetoric, China Matters Most

China is the largest consumer of global crude (9Mbbl/d), receiving a significant amount of its supply (>40 percent) from the Middle East and through the Strait of Hormuz. It has some options to source more crude independent of this volatile chokepoint, such as Canada, Norway or Brazil, all of which are expected to increase production in 2020. However, the only producer with large enough growth in supply to provide China enough mitigation against political uncertainty in the Middle East is the one producing the uncertainty in the first place—the U.S. In this light it is interesting to note that the Phase 1 trade deal signed on Jan. 15 between the U.S. and China includes objectives for China to purchase an additional $52.4bn of U.S. energy products over 2020-21 relative to 2017.

Does China want to rely more heavily on the U.S. for its crude imports, especially within a trade war? Do the strings that would inevitably come with U.S. crude outweigh the political uncertainty in the Middle East and in particular the Strait of Hormuz? Time will tell.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com